UK is stuck in an inflation-stagnation doom loop

By Jon Sindreu

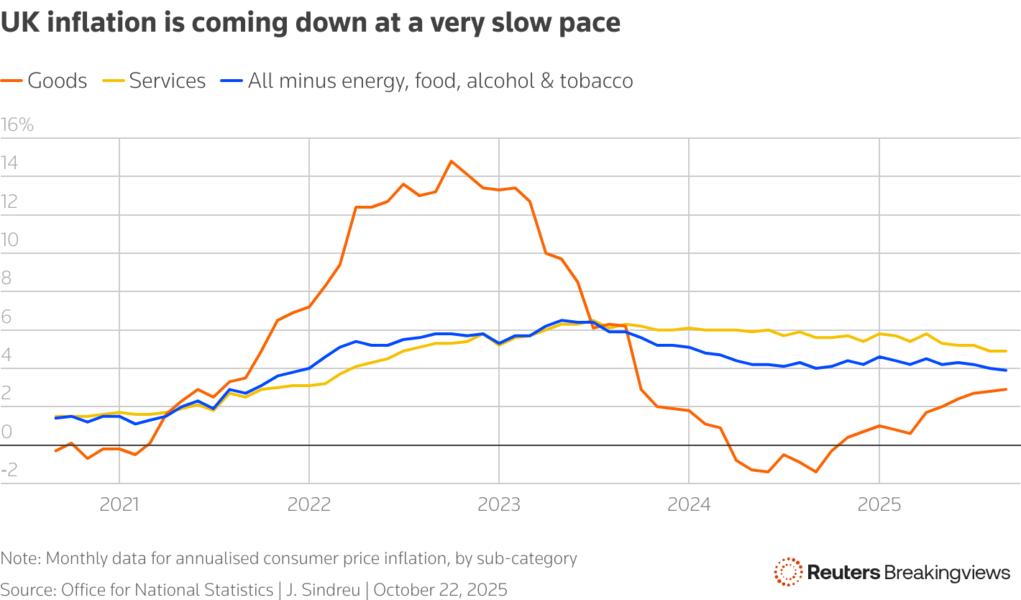

At first glance, Britain's 3.8% annual inflation rate in September looks like great news. It's lower than the 4% economists expected, judging from a Reuters poll, and means that price rises have not accelerated from August and July's levels, giving some relief to finance minister Rachel Reeves ahead of her budget on November 26. But it doesn’t break the negative loop between high prices and weak consumer spending that’s keeping the economy subdued and complicating life for Reeves.

Wednesday’s data does suggest the worst is over. Consumer-price growth was lower than forecast across many categories, including services and non-industrial goods. Meanwhile, wage growth in the private sector continues to cool, with regular pay rising just 4.4% between June and August year-on-year. Traders now price in a 64% chance that the Bank of England (BoE) will cut rates in December, according to data collated by LSEG.

Nonetheless, inflation in the United Kingdom remains far higher than in most wealthy countries, and is roughly double the BoE's 2% target. Services inflation - a key gauge of domestic price pressures - remains at 4.9%. This challenges the traditional view linking inflation to a hot economy, as Britain is experiencing sluggish growth and a deteriorating labour market. Since the pandemic, UK consumption has grown the least among peers.

Rather than an overheating economy, Britain's problem is sticky inflation that started with a post-pandemic price surge, and is now stopping consumers from spending. A 34% rise in gross disposable income since 2019 shrinks to just 6% after inflation. Meanwhile, the UK household savings ratio remains above 10%, a level that since the 1990s has been associated with recessions. High interest rates have eroded bond and real estate wealth.

The upshot: the underlying economy is stronger than it looks and could grow quickly if inflation falls and households spend more freely. That would simplify Reeves’s balancing act between growth and fiscal discipline. September’s decline in food inflation from 5.1% to 4.5% assuages fears of another commodity-led price surge, which had worryingly started showing up in BoE inflation expectations surveys.

But the protracted economic slog is set to continue as long as broader disinflation is so slow, which is a result of monetary policy failing to break the loop. Ratesetter Catherine Mann recently argued that the BoE’s impact on consumption peaked some time ago. Though Reeves will benefit from lower inflation, which feeds into lower debt-servicing costs for inflation-linked bonds, she will still be forced into unpalatable tax rises that could further dent business sentiment. The Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank says deteriorating growth since March will contribute to a 12 billion pound shortfall in her budget. And analysts expect the UK's fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, to downgrade productivity growth again. A brighter long-run economic future hardly matters if short-term woes keep feeding on themselves.

Follow Jon Sindreu on X and LinkedIn.

CONTEXT NEWS

UK annual inflation was 3.8% in September, unchanged relative to August and July, official data showed on October 22. This was lower than economists polled by Reuters were expecting, with inflation in services, core goods and food all coming in below forecasts. Bank of England ratesetters will take this data into account when deciding whether to cut interest rates in November and in December.

Finance minister Rachel Reeves is set to deliver her Autumn Budget on November 26 and she is widely expected to raise taxes. A lower cost of servicing inflation-linked debt will make it easier for her to meet self-imposed fiscal rules. But many analysts also expect the United Kingdom's independent fiscal watchdog to downgrade its forecasts for productivity growth, which would give Reeves less room for maneuver.