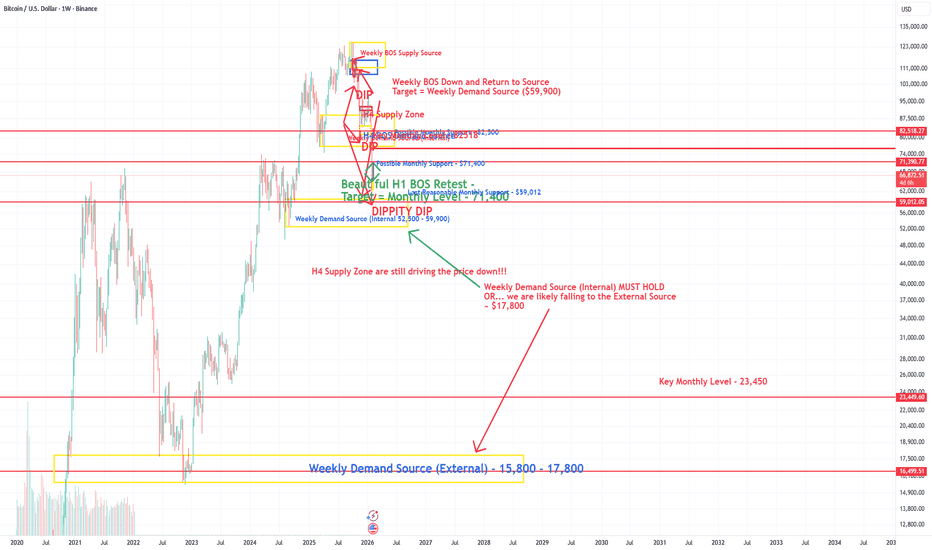

BTC Outlook - Can the "Week" Say I am Strong??!!!!Hey, Traders. Well, BTC is still on this wild ride and things are not looking too good for the Bulls and enthusiasts. If you've been following us, you've seen how this market structure has been playing out near perfectly for those who can understand what is really going on.

The focus for today's post is on the Weekly chart. As the WORD says in Joel 3:10, "let the weak say I am Strong". That is a call to action...to get up and take a stand. Well, for BTC that is the call for right now. If there is any chance that BTC holds up and stands its ground, it is going to be NOW and on the weekly chart. BTCs Week needs to say I am strong! Let's dive in:

Where are we now:

We have seen BTC follow our plan and fall down to near exactly the Weekly Demand Source we highlighted a couple of weeks ago. This level at $59,900 was the initial target after we saw a breakdown of market structure around the $110K price range. That was a 50%+ fall from all time highs, and a huge shock to most of the crypto world. But, it is an awakening to the fact that BTC is not exempt from following market structure, no matter how opportunistic it is. Since hitting this support level, we've seen an expected bullish response and push back up to the last Key Monthly Level we had identified at ~$71,400.

So, What is next?:

From here we are most likely to see a retest of this Weekly Demand Source (52,500 - 59,900). This baby is still falling unless and until we get at least an H4 Break of Structure back up to show that the Bulls have had enough! So far, that has not happened, and so the Fall continues.

We have another Key Monthly level sitting at around $59,012. I'm highlighting that as the last "reasonable" level to keep the price up. This level and the Weekly Demand Source are overlapping so the confluences here MUST be strong enough to hold, or it is Curtains for BTC. We need to watch this Weekly Source closely and look for any cracks in it. If we get an H4 candle close below that $52,500 floor, it is a dangerous sign for BTC. The daily will be the stronger indicator of the problem, so if we get that H4 close below, you need to watch the daily like a hawk!

What if this last support fails:?

If this last line of defense - the Weekly Demand Source (internal) and the Monthly level fail, the only strong support for BTC would be the external Weekly Demand Source way down at 15,800 - 17,800. That is scary but don't think it can't happen. It absolutely can! A weekly candle close below the existing Weekly Demand Source at $52,500 will almost certainly trigger another Major fall. There will likely be some "dead cat bounce" supports at around 40-45K and then again at 25-28K, but again, if the weekly gives up this $52,500 area, it is unlikely that any of these other attempts will stop the price.

So, overall, we are watching this current fall and expecting it to continue until we see signs otherwise. Aggressive traders will stay in sells or shorts until the H4 shows a break of structure...which we have not had yet! Additional sell entries can be taken at new H1 supply zones (or more aggressively at 15 min supply zones).

I hope this helps and that you all are extracting wealth from these markets. Please leave me your comments, questions, thoughts, etc. and if you need any help in learning how to better read the markets, let us know!

Learntotrade

Wow, BTC! The Dip to the Dip to the Dippity DipHey, Traders. Just a quick follow up on our last BTC analysis and how this once again played like a New York Symphony. This structure we have been following led us all the way from ~110K down to EXACTLY the top of this Weekly Demand Source ~$59,900. If you've been following, see our previous posts on BTC and ETH to see how we have been able to follow this market structure and not fall prey to the mass liquidations and gross losses from those who have been longing BTC.

What Happened: The Market played out like the market does. Many players big and small starting buying the DIP on BTC when it fell to around 103K from All Time Highs, not understanding that there was a MUCH bigger picture playing out. They tried again at around the $80 - 85 area when the Market Makers faked most people out and dragged more buyers in for the kill. Unfortunately, the whole time, the Market was seeking this ~$60K area. If you are able to learn how to read and follow what the market is showing, there is almost ALWAYS a few clear signals that can help you stay out of trouble.

What happens now: Now we are sitting at this major Weekly Demand Zone. There are a LOT of buyers for BTC in this area...worldwide volumes of large buyers who have been waiting for everyone else to get liquidated or to tap out, so they can swoop in and buy what is likely to be the World's most valuable asset.

From here, we need to watch this Weekly Zone and look for bullish confirmation out of it. It doesn't mean that the market will automatically start buying, but it does mean the interest in buying is at substantially high levels. We need to watch the H4 in particular in this area and look for a BOS up out of it. The last H4 Supply zone is sitting up near 75K, so it's not likely that it will push up that strong and break that level. We are more likely to make a bullish response on the H4 and create another potential supply zone that can be more easily broken.

Watch for it...wait for it, and if we get it, be ready to buy! As stated in the previous post, aggressive buyers already have longs set at around the ~55K area.

I pray you all are trading safely and staying ahead of the game. If you need help in analyzing and understanding the markets better, let us know and we'll be glad to help. As always, PLEASE leave me your comments, questions, and suggestions, and I'll reply.

DMART – STWP Equity Snapshot📊 DMART – STWP Equity Snapshot

Ticker: NSE: DMART

Sector: Retail / Consumer

CMP: 3,934.9 ▲ (+2.89%)

Learning Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐☆ (Strength Emerging After Demand Response)

Chart Pattern Observed: Range Base → Early Expansion Attempt

Candlestick Pattern Observed: Strong Bullish Range Expansion Candle

📊 Technical Snapshot

DMART has staged a decisive rebound from a previously defended demand zone, printing a wide-range bullish candle supported by expanding participation. The move reflects active buyer presence after a prolonged balancing phase, suggesting that the market is transitioning from contraction toward expansion.

Price is now approaching the upper boundary of the recent value area, where prior supply reactions have historically emerged. Acceptance above this region would indicate value migration higher, while failure to sustain could lead to temporary rebalancing within the range.

From a CPR perspective, the structure is shifting upward with a projected wide CPR — typically associated with trending environments rather than sideways behaviour. This alignment subtly strengthens the probability of directional continuation, provided participation remains supportive.

Overall structure signals improving momentum, but extension risk must be respected after a sharp single-session expansion.

📊 Volume Analysis

🔹 Current Volume: ~867K

🔹 20-Period Average: ~540K

⚖️ Participation has expanded meaningfully above average, indicating institutional interest rather than purely retail activity.

💡 Interpretation:

Breakouts backed by volume expansion tend to carry better structural reliability than low-participation moves. Sustained volume will be the key validator of whether this is accumulation continuation or merely a short-term price spike.

🔑 Key Levels – Daily Timeframe

Support Areas: 3856 | 3778 | 3732

Resistance Areas: 3981 | 4027 | 4105

These are zones where price has paused or reacted earlier.

What’s Catching Our Eye: Strong demand-led expansion emerging from a defended base.

What to Watch For: Sustained acceptance above the near-term value zone.

Failure Zone: Loss of structure below the immediate support cluster.

Risks to Watch: Post-expansion cooling or short-term profit rotation.

What to Expect Next: Potential continuation attempt with intermittent consolidation.

📌 Price Reference Framework – Educational View

🔹 Intraday Reference (Short-Term Observation)

Observation Zone: 3,949

Risk Invalidation Area: Below 3,741

Upside Reference Zones: 4,198-4,365

Used only to observe near-term price behaviour.

🔹 Swing Reference (Positional | Multi-Session Observation)

Observation Zone: 3,935-3949

Risk Invalidation Area: Below 3,638

Upside Reference Zones: 4,572 → 5,039 (structure projection)

Relevant only if price sustains above the evolving value region.

STWP View

Momentum: Strengthening

Trend: Attempting Upward Transition

Risk: Elevated After Expansion

Volume: Supportive

🧠 Learning Note

Strong candles attract attention — strong structure sustains trends. Always evaluate participation and acceptance before forming directional bias.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This post is shared purely for educational and informational purposes and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation. Please consult a SEBI-registered financial advisor before making any trading or investment decisions. Market participation involves risk.

💬 Did this help you understand the chart better?

🔼 Boost | ✍️ Comment | 🔁 Share with a learner

👉 Follow STWP for structure-based market education

🚀 Stay Calm. Stay Clean. Trade With Patience.

It's Freezing Cold Outside - Is BTC Headed for Winter, Too???Hey, Traders. Wow, we have had some wild rides in crypto the past few months. If you've been following any of my analyses, you can see that nearly everything has been playing out according to the way we read market structure. Forgetting all of the news, politics, and the many other fundamental factors out there, BTC and ETH have been following a solid technical structure that few have learned to discern. And now...that same technical structure has been showing me that something even bigger has been brewing. We have mostly been watching these on the H4 and Daily Charts, but behind the scenes the Weekly Time frame has been playing its own song....We'll dive into this top down view of BTC today!

What is going on?:

Once we zoom out and look at the weekly, here is what has happened.

We had a weekly Break of Structure back the week of 10/13...Remember that crazy Oct 10th Day when there was a so called "Flash Crash". Well this was more than a glitch in some Exchanges networks - it was a choreographed move that was predetermined and brought BTC to near exactly where it needed to be to plan the next big move. This BOS then returned back to the Weekly Source and was rejected the week of Oct 27th...further legitimizing the original BOS move down.

As I have indicated many times, this kind of move nearly always results in a return to the Demand Source. At the time of that Signal, BTC was at ~110K...just coming off of All Time Highs, and the Demand Source is way down at ~60K...Inconceivable, right???? WRONG! It's Very conceivable.

Could this really happen?:

On the H4 and Daily charts, we have been taking buys and sells according to those structures, but we cannot forget that the Weekly is the stronger, more dominant director of what the market is really doing. It's easy to get lost in the ups and downs of H4 and daily candles, because there are a lot of good trade opportunities there. But, here is what the weekly is showing and how this could actually happen...

There is an internal Weekly Demand Source (77K - 89K). We are currently inside of this structure now. I say this is internal because the Demand is there, but there was not enough market time in this area in the past to make it a strong enough area of demand. So, it could hold the price and provide support, but it is unlikely to be the solid bottom we need for a strong bull run. Just from the last Daily BOS and its return, we are headed to test at least 85-87K. So, here are the next possible steps:

1. IF this internal Source does not hold, it's very likely falling to the Monthly Key Level at ~ 71.4K. That is literally the last opportunity for BTC to hold up.

2. If the Monthly level doesn't hold it, there's an unfilled FVG at 73.6K that will try to stop it.

3. If that fails, its down to the 60K Weekly Demand Zone.

If we hit this 60K level, its going to be the BUY of BUYS for BTC. Aggressive traders will already have limit orders to buy there, with stops around 55K.

As always, I hope this helps some of you. Please leave me any comments or questions and I'll be happy to respond. If you are looking for a solid and consistent way to extract wealth from these markets, let us know. We'd love to help you!

IS BTC Finally Booming Again? Not So Fast! The Daily BOS UpHey, Traders. BTC has had some significant pushes these last few days and it has been surprising to many. But, if you've been following our posts on ETH and our structural analyses, you can see how this has been playing beautifully like a flute! Please see our previous posts for more details.

Where are we now?

BTC has been playing out a H4 Structure the last few days. This started with an H4 Break of Structure Up back on Dec 2 when it closed above 92,500. This BOS was a good push up, but as we have shown here numerous times, it usually leads to a significant pull back to the Source. In this case, the source was around 84,600. We saw BTC fall exactly back to this area. To many this seemed like another crash and there were many posts, speculations, etc. about Fed rates, Gold Pumps, etc. But to keen technical traders, this was all expected, and offered a great opportunity to buy at around $85K.

This return to the H4 Source set the way for BTC to push back up to the Daily Supply Zone (94,500 - 96,800) where we are today. There was little to nothing to stop it from returning here after the H4 Confirmation.

So, What's Next?:

At today's close, BTC gave a Daily BOS Up, with a close above this Daily Supply Zone ~96,700. This has been long awaited, and is the first Strong Bullish sign since we fell from ATH in October. So, this is the first Real signal that the BTC fall is over (the lows have been put in around 80K). Now, what we should expect from here is two-fold:

1. In my analyses, A BOS up almost always leads to a pullback return to the Source. In this case, the Daily Source is (80,500 - 87,500). That is a large area, so I would look for the H4 source within that zone (80,500 - 84,500) for the most likely pullback area. This is the strongest and most likely scenario.

2 . The only way we don't fall back to this Daily Source area is with a strong Retest and Rejection of this latest Daily Supply Zone. This is not as likely, but could happen. The Retest needs to be strong, though. We need to see a Daily bearish candle push significantly back into this Daily supply zone, but get rejected hard and end up closing back above the top of the zone - above 96,700. If that happens, then we need another strong bullish daily candle away from the zone. These MUST happen to keep BTC going up. If we get this pattern, then it's off to the races and there will only be a few insignificant resistance areas (110K - 112K) and (114K - 115K) that will slow it down on its way back to near ATH. I'd expect a push back to 123K, and then a strong re-assessment from there.

So, that's what I see playing out on BTC. Please leave me your comments, suggestions, etc. as I would love to hear from you. Also, if you don't have strong technical analysis skills and would like to learn how we "READ" the markets, drop me a line and I'd be glad to discuss our training programs with you. Happy Trading!!!

The Insider Intel Community Is Now Live!We’re excited to announce that our new Insider Intel Community is officially open — built for traders who want to level up their analysis, connect with others, and discuss real market structure setups across Forex and Stocks.

Inside the community, members can access two dedicated trading hubs:

💹 The Trading Floor FX – Focused on Forex price action, ICT concepts, and macro drivers.

📈 The Equity Exchange – Covering stock setups, swing ideas, and long-term plays.

We’re posting more frequent breakdowns, setups, and weekly bias updates within the community to keep discussions structured and informative. You’ll also find built-in trading tools like a heat map, news feed, and economic calendar to support your analysis workflow.

This is a space for traders who value structure, collaboration, and clarity — designed to learn, share, and grow together.

If you’re part of the Insider Intel network, you can now explore the new community area directly through our main portal.

Stay sharp. Trade smart.

— Insider Intel Team

Tesla (TSLA) | Maintaining Bullish Structure & Supporting Key Levels

Tesla continues to show strong bullish structure across the higher timeframes.

Price has respected the monthly Fibonacci golden zone (234–212) as a solid re-entry area, aligning with a bullish order flow and structural break to the upside.

We can see price now consolidating above a key monthly POI (around 384–359), forming a potential continuation zone as it builds liquidity for the next leg higher.

The long-term bullish projection remains intact, with extended targets toward 831–850, completing a full swing move if momentum persists.

The overall structure remains supported by broader NASDAQ tech strength, reinforcing Tesla’s alignment with sector performance.

In our private trading discussions, we explore deeper setups like this — identifying structure shifts, key liquidity pools, and macro confluence zones across multiple assets.

Disclaimer: This analysis is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Always do your own research (DYOR) before making investment decisions.

Happy New Year, Happy New ETH???Happy New Year, Traders! I pray you all are off to a wonderful start to the new year. We've been off for the Holidays, but we're back and ready to tackle the markets again. So, what in the world is going on with ETH and BTC? Things are looking up for the start of the year, so let's dive in and see what's happening. My primary focus is always on the H4 and up for market direction and diving down to the H1 only sparingly for more detailed looks.: Please see my previous posts on ETH in Nov and Dec to see how we got here.

Where are we now?:

Well, over the Holidays, we had an H4 BOS UP. This move is very important, because it is the first Significant Move out of the Daily BOS Source. As I have emphasized, a BOS UP almost always leads to a retracement back to the source, and that is what we saw. We had the initial BOS Up on Dec 22, and came back to the source on the 24th. Then, on Jan 2 we got a confirmation of this move with the retest of the broken H4 supply zone. Once again, as I have emphasized, this confirmed BOS up will almost always lead to a target of the H4 Supply Source Or the Daily Supply. This is ~3360 - 3520. As of today, the market has pushed up 2/3 of the way to this target.

What to expect from here?:

From here, again, we are 2/3 of the way to this target area. There are a few H4 Internal Supply Zones that will likely show some resistance. We need to expect these zones to slow things down and show some pullbacks, but they WILL NOT hold. Possible trade opportunities are:

1. Look for H1 demand zones and buy on the way up. Aggressive traders can simply buy every pullback on the H1 to the previous demand zone. These trades should have small stop losses below the demand zone and targets at the new high. Every significant new high should lead to a pullback to the demand zone. Any BOS down on the H1 will most likely lead to a fall back to the previously broken H4 Supply Zone, so you want to get out if you see this, and wait for the lower re-entry.

2. On the H4, look for any of these previous supply zones that have been broken but not retested. The current H4 supply zone at 3120 - 3175 is a good example. We have pushed above this zone, but there is no retest of it. I'm looking for pullbacks back to this zone for another buy entry.

I hope this helps someone who is trying to make sense out of these seemingly wild rides since the New Year. As I have emphasized before, these type of moves have very little to do with external news events, but are solid structural moves that ANYONE can learn to "READ" on ANY ASSET. If you're struggling to decipher the markets and are seemingly always "late to the game", let us help you learn and grow!

As always, please leave me your comments, suggestions, and questions, and I'll be glad to respond. We have mostly been posting ETH moves as an example of how we read the markets, but we are trading a lot of different assets. If you have one you've been struggling with, or just a favorite that you like to trade, let me know in the comments, and I'll try to help.

Again, Happy New Year and be blessed!!!

Reading institutional intentions through Volume ProfileReading institutional intentions through Volume Profile

Price moves where money flows. Simple truth that most traders overlook the most obvious source of money information: volume.

Volume Profile shows where trading happened. Not when, but where. The histogram on the side reveals which levels attracted buyers and sellers. While beginners draw support lines by candle wicks, money flows elsewhere.

Value zones versus noise zones

Point of Control (POC) marks the price level with maximum trading volume for the period. Price spent most time here. Buyers and sellers agreed on this price. Fair value at this moment.

Value Area covers 70% of traded volume. Boundaries of this zone show where the market considers the asset undervalued or overvalued. Price gravitates back to Value Area like a magnet.

Look at the practice. Price broke the high, everyone expects growth. Check Volume Profile—volume on the breakout is tiny. Big players didn't participate. Fake breakout. Price will return.

High Volume Node and Low Volume Node

HVN appears as thick sections on the profile. Many transactions, lots of liquidity. Price slows down at HVN, reverses, consolidates. These are market anchors.

LVN shows as thin sections. Few transactions, little liquidity. Price flies through LVN like a hot knife through butter. Nothing to grab onto there.

Traders often place stops behind HVN. Big players know this. Sometimes price deliberately hits those stops to accumulate positions. Called stop hunt .

Profile types and their meaning

P-shaped profile: one wide POC in the middle, volume distributed evenly. Market in balance. Breaking boundaries of such profile produces strong moves.

b-shaped profile: volume shifted to the bottom. Buyers active at low levels. Accumulation before growth.

D-profile: volume at the top. Distribution before decline. Big players exit positions.

Using profile in trading

Find areas with low volume between zones of high volume. LVN between two HVNs creates a corridor for fast price movement. Enter at HVN boundary, target the next HVN.

When price moves outside Value Area boundaries and volume appears there—trend gains strength. New value zone forms. Old levels stop working.

If price returns to old Value Area after strong movement—look for reversal. Market rejects new prices.

Session profiles versus weekly ones

Daily profile shows where trading happened today. Weekly shows where positions accumulated all week. Monthly gives the picture of big money distribution.

Profiles of different periods overlay each other. Daily profile POC can match weekly Value Area boundary. Strong zone. Price will react here.

On futures, account for session times:

Asian session forms its profile

European forms its own

American forms its own, with heavier volume weight

Profile rotation

Price migrates between value zones. Old Value Area becomes support or resistance for the new one. Last week's POC works as a magnet on current week.

When profiles connect—market consolidates. When they separate—trend begins.

Volume and volatility

Low volume at some level means price didn't linger there. Passed quickly. On return to this level, reaction will be weak.

Volume grows at range boundaries. Battle of buyers and sellers happens there. Winner determines breakout direction.

Composite profile

Built from several trading days. Shows where main battle happened over the period. Removes noise of individual days. Picture becomes clearer.

Composite profile helps find long-term support and resistance zones. Monthly composite shows levels institutional traders will work from all next month.

Many traders build Volume Profile directly on Trading View charts. Adjust the period, watch volume distribution, plan trades.

How to Find Support and Resistance Levels That Actually WorkHow to Find Support and Resistance Levels That Actually Work

Price never moves in a straight line. It bounces off invisible barriers, pauses, reverses. These barriers are called support and resistance levels.

Sounds simple. But traders often draw lines where they don't exist. Or miss truly strong zones. Let's figure out how to find levels where price reacts again and again.

What Support and Resistance Are

Imagine a ball thrown in a room. It hits the floor and ceiling. The floor is support, the ceiling is resistance.

Support works from below. When price falls to this zone, buyers activate. They consider the asset cheap and start buying. The decline slows or stops.

Resistance works from above. Price rises, reaches a certain height, and sellers wake up. Some lock in profits, others think the asset is overvalued. Growth slows down.

Why Levels Work at All

Thousands of traders look at the same chart. Many see the same reversal points in the past.

When price approaches this zone again, traders remember. Some place pending buy orders at support. Others prepare to sell at resistance. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The more people noticed the level, the stronger it is.

Where to Look for Support and Resistance

Start with weekly or daily charts. Zoom out to see history for several months or years.

Look for places where price reversed multiple times. Not one bounce, but two-three-four. The more often price reacted to a level, the more reliable it is.

Look at round numbers. Trader psychology works so that levels like 100, 1000, 50 attract attention. Orders cluster around these marks.

Look for old highs and lows. A 2020 peak can become resistance in 2025. A crisis bottom turns into support a year later.

Drawing Levels Correctly

A level is not a thin line. It's a zone several points or percent wide.

Price rarely bounces from an exact mark. It can break through a level by a couple of points, collect stop-losses and return. Or stop a bit earlier.

Draw a horizontal line through candle bodies, not through wicks. Wicks show short-term emotional spikes. The candle body is where price closed. Where traders agreed on a compromise.

Don't clutter your chart with a hundred lines. Keep 3-5 most obvious levels. If you drew 20 lines, half of them don't work.

How to Check Level Strength

Count touches. Three bounces are more reliable than one. Five bounces - that's a powerful zone.

Look at volume. If there's lots of trading at a level, it confirms its significance. Large volume shows major players are active here.

Pay attention to time. A level that worked five years ago may lose strength. Fresh levels are usually stronger than old ones.

When a Level Breaks

A breakout happens when price closes beyond the level. Not just touched with a wick, but closed.

After a breakout, support becomes resistance. And vice versa. This is called polarity shift. Traders who bought at old support now sit in losses and wait for return to entry point to exit without losses.

A breakout must be confirmed. One candle beyond the level is not a breakout yet. Wait for the day to close, check volume, verify price didn't return.

False breakouts happen all the time. Major players deliberately knock out stops to collect liquidity.

Common Mistakes

Traders draw levels on small timeframes. A five-minute chart is full of noise. Levels from hourly or daily charts work better.

Traders ignore context. Support in an uptrend is stronger than in a downtrend. Resistance in a falling market breaks easier.

Traders enter exactly at the level. Better to wait for a bounce and confirmation. Price can break through a level by several points, knock out your stop, then reverse.

Diagonal Levels

Support and resistance aren't only horizontal. Trendlines work as dynamic levels.

In an uptrend, draw a line through lows. Price will bounce from this line upward.

In a downtrend, connect highs. The line becomes dynamic resistance.

Trendlines break just like horizontal levels. A trendline break often signals a trend reversal.

Combining with Other Tools

Levels don't work in isolation. Their strength grows when they coincide with other signals.

A level at a round number + cluster of past bounces + overbought zone on an oscillator - this is a powerful combination for finding reversals.

Traders often add technical indicators to their charts to help confirm price reaction at levels. This makes analysis more reliable and reduces false signals.

How to survive a losing streak without blowing up your accountHow to survive a losing streak without blowing up your account

Drawdown hits the account, but the real damage lands in your head.

A real trading career always includes stretches of pure red. Five, seven, even ten losses in a row can appear without anything "being wrong" with the setup. At that point the market stops looking like candles and levels, and starts looking like a personal enemy. Without a plan written in advance, the usual reaction is to increase size and "win it back."

The drawdown itself is not the main threat. The danger sits in what happens inside the drawdown: revenge trades, oversized positions, random entries just to feel in control again.

Turn the losing streak into numbers

The feeling "everything goes wrong" is vague and dangerous. Numbers are less emotional.

Simple tracking is enough:

Current drawdown in percent from the equity peak

Number of losing trades in a row

Total hit of the streak in R (risk units per trade)

Example: risk per trade is 1%, and you take five consecutive stops. That is -5%. With a personal limit of 10% drawdown, the account is still alive, but the mind is already tense. At that point the numbers matter more than mood. They show whether there is still room to act or time to stop and regroup.

Why losing streaks bend your thinking

The market does not change during a streak. The trader does.

Typical thoughts:

"The strategy is dead" after only a few stops

Desire to prove to the market that you were right

Sudden shift from clear setups to anything that "might move"

In reality it is normal distribution at work. Losses cluster. Most traders know that in theory, but very few accept it in advance and prepare a plan for that specific phase.

Build a risk frame for bad runs

Risk rules for streaks should live in writing, not in memory.

For example:

Define 1R as 0.5–1% of account size

Daily loss limit in R

Weekly loss limit in R

Conditions for a mandatory trading pause

A simple version:

1R = 1%

Stop trading for the day once -3R is reached

Stop trading for the week once -6R is reached

After a weekly stop, take at least two market sessions off from active trading

This does not make performance look pretty. It simply keeps one emotional spike from turning into a full account blow-up.

A protocol for losing streaks

Rules are easier to follow when they read like a checklist, not a philosophy.

Sample protocol:

After 3 consecutive losses: cut position size in half for the rest of the day

After 4 consecutive losses: stop trading for that day

After 5 or more consecutive losses: take at least one full day off and do only review and backtesting

Return to normal size only after a small series of well-executed trades where rules were respected

Printed rules next to the monitor work better than "mental promises." In stress the brain does not recall theory, it reads whatever sits in front of the eyes.

A drawdown journal

A regular trade log tracks entries and exits. During drawdowns you need an extra layer dedicated to the streak.

For each drawdown period, you can record:

Start date and equity at the beginning

Maximum drawdown in percent and in R

Main source of damage: risk, discipline, setup quality, or flat market conditions

Any mid-streak changes to the original plan

Outside factors such as sleep, stress, or heavy workload

After some months, the journal starts to show patterns. Many discover that the deepest drawdowns came not from the market, but from trading while tired, distracted, or under pressure outside the screen.

Coming back from a drawdown

The drawdown will end. The key part is the exit from it. Jumping straight back to full size is an easy way to start a new streak of losses.

You can describe the return process in stages:

Stage 1. One or two days off from live trading. Only review, markups, statistics.

Stage 2. Half-size positions, only the cleanest setups, strict cap on trade count.

Stage 3. Back to normal risk after a short series of trades where rules were followed, even if the profit is modest.

The drawdown is over not when the equity line prints a new high, but when decisions are again based on the plan instead of the urge to "get it all back."

Where tools and indicators help

A big part of the pressure in a streak comes from the mental load: levels, trend filters, volatility, news, open positions. That is why many traders rely on indicator sets that highlight key zones, measure risk to reward, send alerts when conditions line up, and reduce the need to stare at the screen all day. These tools do not replace discipline, but they take some of the routine off your plate and give more energy for the hard part: staying calm while the equity curve is under water.

A daily trading plan: stop trading your moodA daily trading plan: stop trading your mood and start trading your system

Most traders think they need a new strategy. In many cases they need a clear plan for the day.

Trading without a plan looks very similar across accounts. The platform opens, eyes lock onto a bright candle, the button gets pressed. Then another one. The mind explains everything with words like “intuition” or “feel for the market”, while the journal in the evening shows a pile of unrelated trades.

A daily plan does not turn trades into perfection. It removes chaos. The plan covers charts, risk, loss limits, number of trades and even the trader’s state. With that in place, the history starts to look like a series of experiments instead of casino slips.

Skeleton of a daily plan

A practical way is to split the day into five blocks:

market overview from higher timeframes

watchlist for the session

risk and limits

scenarios and entry checklist

post-session review

The exact form is flexible. The important part is to write it down instead of keeping it in memory.

Market overview: higher timeframe sets the background

The day starts on the higher chart, not on the one-minute screen. H4, D1 or even W1. That is where major swings, large reaction zones and clear impulses live.

A small template helps:

main asset of the day, for example BTC or an index

current phase: directional move or range

nearest areas where a larger player has strong reasons to act

Descriptions work best when they are concrete. Not “bullish market”, but “three higher lows in a row, shallow pullbacks, buyers defend local demand zones”. A month later these notes show how thinking about trend and risk evolved.

Watchlist: stop chasing every ticker

Next layer is a focused list of instruments. With less experience, a shorter list often works better. Two or three names are enough for the day.

Selection can rely on simple filters:

recent activity instead of a dead flat chart

structure that is readable rather than random noise

enough liquidity for clean entries and exits

Once the list is fixed, outside movement loses some emotional grip. Another coin can fly without you, yet the plan keeps attention on the few markets chosen for that day.

Risk and limits: protection from yourself

This block usually appears only after a painful streak. Until then the brain likes the story about “just this one time”.

Minimal set:

fixed percentage risk per trade

daily loss limit in R or percent

cap on number of trades

For example, 1% per trade, daily stop at minus 3R, maximum of 5 trades. When one of these lines is crossed, trading stops even if the chart shows a beautiful setup. That stop is not punishment. It is a guardrail.

Breaking such rules still happens. With written limits, each violation becomes visible in the journal instead of dissolving in memory.

Scenarios and entry checklist

After the bigger picture and limits are set, the plan moves to concrete scenarios. Clarity beats variety here.

For every instrument on the list, write one or two scenarios:

area where a decision on price is expected

direction of the planned trade

SEED_ALEXDRAYM_SHORTINTEREST2:TYPE of move: breakout, retest, bounce

[*stop and targets in R terms

Example: “ETHUSDT. H4 in an uptrend, H1 builds a range under resistance. Plan: long on breakout of the range, stop behind the opposite side, target 2–3R with partial exit on fresh high.”

An entry checklist keeps emotions in check.

$ trade goes with the higher-timeframe narrative

$ stop stands where the scenario breaks, not “somewhere safer”

$ position size matches the risk rules

$ trade is not revenge for a previous loss

If at least one line fails, entry is postponed. That small pause often saves the account from “just testing an idea”.

Post-session review: where real learning sits

The plan lives until the terminal closes. Then comes the review. Not a long essay, more like a short debrief.

Screenshots help a lot: entry, stop, exit marked on the chart, with a short note nearby.

was there a scenario beforehand

did the market behave close to the plan

which decisions looked strong

where emotions took over

Over several weeks, this archive turns into a mirror. Profitable setups repeat and form a core. Weak habits step into the light: size jumps after a loss, early exits on good trades, stop removal in the name of “room to breathe”.

Where indicators fit into this routine

None of this strictly requires complex tools. A clean chart and discipline already move the needle. Many traders still prefer to add indicators that highlight trend, zones, volatility and risk-to-reward, and ping them when price enters interesting regions. That kind of automation cuts down on routine work and makes it easier to follow the same checklist every day. The decision to trade still stays with the human, while indicators quietly handle part of the heavy lifting in the background.

$META | COVERAGE INITIATED — Personal Position Update [W49]COVERAGE INITIATED — Bullish Classification (Trend Shift Identified)

META — WEEK 49 TREND REPORT | 12/05/2025

Ticker: NASDAQ:META

Timeframe: W

This is a reactive structural classification based on the weekly chart as of this timestamp. Price conditions are evaluated as they stand — nothing here is predictive or forward-assumptive.

⸻

Author’s Note — Personal Position Update

I initiated my own position on [ NASDAQ:META ] during Week [ 49 ], entering at $ [ 673.42 ].

This decision follows my personal criteria: I only participate when my system identifies a verified structural trend shift supported by both a confirmed weekly flag and a qualifying candle state. This note reflects my activity only and is not a suggestion for anyone else.

As of this update, my position is currently up ~ [ 0% ] from my entry.

My structural exit level is $ [ 670.20 ] on a weekly-close basis. This level will continue to adjust upward automatically as the structure strengthens. If price closes below that threshold, my system classifies the trend as structurally compromised, and that is where I personally exit.

This update exists solely to document my own participation and the structural levels I monitor. It is not predictive and does not imply any future outcome.

⸻

Structural Integrity

• 1) Current Trend Condition [ Numbers to Watch ]

• Current Price @ $

• Trend Duration @ +0 Weeks

( Bullish )

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish ) @ $

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish Confirmation ) @ $

• Pullback Correction Retracement @ $

• Correction Structural Support @ $

⸻

2) Structure Health

• Retracement Phase:

Uptrend (operating above 78.6%)

• Position Status:

Caution (interacting with structural layers)

⸻

3) Temperature :

Warming Phase

⸻

4) Momentum :

Neutral

⸻

Structural Alignment

NEUTRAL STRUCTURAL CONDITION

This mark represents a period where directional behavior was unclear. Market movement here reflected compression, chop, or indecision — neither trend direction was dominant. It does not signal continuation or reversal, only that price action was not showing strong alignment in either direction.

⸻

Methodology Overview

This classification framework evaluates directional conditions using internal trend-interpretation logic that references price behavior relative to its structural layers. These relationships are used to identify when price movement aligns with the framework’s criteria for directional phases, transition points, or regime shifts. Visual elements or structural labels reflect these internal interpretations, rather than explicit trading signals or preset indicator crossovers. This framework is observational only and does not imply future outcomes.

$PLTR | COVERAGE INITIATED — Personal Position Update [W49]COVERAGE INITIATED — Bullish Classification (Trend Shift Identified)

PLTR — WEEK 49 TREND REPORT | 12/05/2025

Ticker: NASDAQ:PLTR

Timeframe: W

This is a reactive structural classification based on the weekly chart as of this timestamp. Price conditions are evaluated as they stand — nothing here is predictive or forward-assumptive.

⸻

Author’s Note — Personal Position Update

I initiated my own position on [ NASDAQ:PLTR ] during Week [ 49 ], entering at $ [ 181.76 ].

This decision follows my personal criteria: I only participate when my system identifies a verified structural trend shift supported by both a confirmed weekly flag and a qualifying candle state. This note reflects my activity only and is not a suggestion for anyone else.

As of this update, my position is currently up ~ [ 0% ] from my entry.

My structural exit level is $ [ 177.54 ] on a weekly-close basis. This level will continue to adjust upward automatically as the structure strengthens. If price closes below that threshold, my system classifies the trend as structurally compromised, and that is where I personally exit.

This update exists solely to document my own participation and the structural levels I monitor. It is not predictive and does not imply any future outcome.

⸻

Structural Integrity

• 1) Current Trend Condition [ Numbers to Watch ]

• Current Price @ $

• Trend Duration @ +0 Weeks

( Bullish )

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish ) @ $

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish Confirmation ) @ $

• Pullback Retracement @ $

• Correction Support @ $

⸻

2) Structure Health

• Retracement Phase:

Uptrend (operating above 78.6%)

• Position Status:

Healthy (price above both structural layers)

⸻

3) Temperature :

Neutral Phase

⸻

4) Momentum :

Bullish

⸻

Structural Alignment

NEUTRAL STRUCTURAL CONDITION

This mark represents a period where directional behavior was unclear. Market movement here reflected compression, chop, or indecision — neither trend direction was dominant. It does not signal continuation or reversal, only that price action was not showing strong alignment in either direction.

⸻

Methodology Overview

This classification framework evaluates directional conditions using internal trend-interpretation logic that references price behavior relative to its structural layers. These relationships are used to identify when price movement aligns with the framework’s criteria for directional phases, transition points, or regime shifts. Visual elements or structural labels reflect these internal interpretations, rather than explicit trading signals or preset indicator crossovers. This framework is observational only and does not imply future outcomes.

$SHOP | COVERAGE INITIATED — Personal Position Update [W49]COVERAGE INITIATED — Bullish Classification (Trend Shift Identified)

SHOP — WEEK 49 TREND REPORT | 12/05/2025

Ticker: NASDAQ:SHOP

Timeframe: W

This is a reactive structural classification of SHOP based on the weekly chart as of this timestamp. Price conditions are evaluated as they stand — nothing here is predictive or forward-assumptive.

⸻

Author’s Note — Personal Position Update

I initiated my own position on [ NASDAQ:SHOP ] during Week [ 49 ], entering at $ [ 161.08 ].

This decision follows my personal criteria: I only participate when my system identifies a verified structural trend shift supported by both a confirmed weekly flag and a qualifying candle state. This note reflects my activity only and is not a suggestion for anyone else.

As of this update, my position is currently up ~ [ 0% ] from my entry.

My structural exit level is $ [ 159.19 ] on a weekly-close basis. This level will continue to adjust upward automatically as the structure strengthens. If price closes below that threshold, my system classifies the trend as structurally compromised, and that is where I personally exit.

This update exists solely to document my own participation and the structural levels I monitor. It is not predictive and does not imply any future outcome.

⸻

Structural Integrity

1) Current Trend Condition [ Numbers to Watch ]

• Current Price @ $

• Trend Duration @ +0 Weeks

( Bullish )

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish ) @ $

• Trend Reversal Level ( Bearish Confirmation ) @ $

• Pullback Retracement @ $

• Correction Support @ $

⸻

2) Structure Health

• Retracement Phase:

Uptrend (operating above 78.6%)

• Position Status:

Healthy (price above both structural layers)

⸻

3) Temperature :

Neutral Phase

⸻

4) Momentum :

Bullish

⸻

Structural Alignment

UPWARD STRUCTURAL ALIGNMENT

This mark reflects a point where market behavior supported the continuation of the existing upward direction. It does not imply forecasting or targets — it simply notes where strength became observable within the current trend. Its meaning holds only while price continues to respect the broader structural levels that define the trend.

⸻

Methodology Overview

This classification framework evaluates directional conditions using internal trend-interpretation logic that references price behavior relative to its structural layers. These relationships are used to identify when price movement aligns with the framework’s criteria for directional phases, transition points, or regime shifts. Visual elements or structural labels reflect these internal interpretations, rather than explicit trading signals or preset indicator crossovers. This framework is observational only and does not imply future outcomes.

How to Use Simple Moving Averages (SMA) to Predict Price TargetsIn this video, you’ll learn exactly how to use the Simple Moving Average (SMA) to find both short-term and long-term price targets.

I explain which SMA settings work best, how to spot trend direction, and most importantly:

When you should take a trade and when you should stay OUT of the market to avoid losses.

What You’ll Learn:

How the Simple Moving Average works (SMA 9, 21, 50)

How to use SMA for short-term and long-term price targets

Best SMA crossover strategies

When to enter a trade using SMA

When to stop trading / avoid traps

How institutions use SMA to set levels

Tips to improve your accuracy and timing

USDHKD Forex Pair is exploding as expectedMost traders keep chasing candles on the 5-minute chart, hoping to find magic. But magic doesn’t happen there — it happens when you learn to wait.

The USD/HKD Forex pair is the perfect example. We called the monthly demand level at 7.77 weeks ago, and look at it now — it’s reacting beautifully.

The big boys are buying while everyone else is still guessing. Let’s dive into the chart and see why this pair is offering both swing and intraday opportunities right now!

USDHKD Forex Analysis and Forecast

The USD/HKD Forex pair is doing exactly what supply and demand imbalances told us it would do.

The monthly demand level at 7.77 — the one we discussed in our last analysis — is playing out beautifully. Price reached this imbalance, and once again, demand took full control.

This isn’t the first time the US dollar has bounced hard from around the 7.75–7.78 range. Historically, whenever the dollar dips near that area, strong buyers step in, triggering a powerful bullish reaction.

Now, as the pair rallies from this strong monthly demand, we can already see strong impulses on the daily, 4H, and 1H timeframes. These are early signs of new buyers entering the market — perfect for Forex swing traders and intraday traders alike.

SUCCESS OR FAILURE: MINDSET OR SKILLS?Anfibo's here. Today, I wanna share you guys my valuable experience.

For new traders who just want to trade, after learning the basics, your strategy boils down to 4 things:

Fundamental Analysis (FA)

Technical Analysis (TA)

Fund Management (FM)

Risk Management (RM)

Think of it like a battle. The market is the battlefield, and you’re the warrior:

FA and TA are your sword and spear. The more you sharpen these skills, the better your edge in trading.

FM and RM are your shield and armor. Manage them well, and you’ll stay protected and survive longer.

But gear alone isn’t enough to win!

MINDSET—like a warrior’s spirit—is the real key to success or failure. Here are 6 common psychological factors, or keywords that every trader faces:

1. TREND FOLLOWING: The trend is your friend. Don’t fight it!

2. OPPORTUNITY COST: In the end, we only regret the chances we didn’t take

3. ENDOWMENT EFFECT: This is when you overvalue something just because you own it. Don’t fall in love with your trades—overpricing them leads to disaster!

4. ANCHORING EFFECT: This happens when you cling to the first piece of info you get and base decisions on it, even if it’s wrong. Don’t let one bit of news steer your choices.

5. GREED: Wanting too much can backfire. Greed leads to mistakes!

6. DECISIVE: Be bold. Hesitating at key moments can cost you.

I call these six keywords my “SIX-WORD MANTRA.” Why? Because in trading, mindset controls 60% of your success or failure. Skills make up the other 40% —and if you’re not great at them, you can lean on others’ expertise.

That’s why I always tell newbies: at the very least, learn enough to read someone else’s chart, spot the entry and stop-loss points, and make your own decisions. Don’t just blindly follow some influencer or “expert” online shouting to buy something—that’s a recipe for trouble if you lack knowledge or your own judgment!

What’s your take? Drop a comment, and let’s discuss!

If you agree with me, follow me to read more of my good articles.

And I’m An, just sharing what I know about finance ;)

Geopolitical Tensions & Trade Wars1. Understanding Geopolitical Tensions

Definition

Geopolitical tensions refer to conflicts or rivalries between nations that arise from differences in political systems, territorial claims, military strategies, or economic interests. These tensions often extend beyond diplomacy into military confrontations, sanctions, cyber warfare, and trade restrictions.

Key Drivers of Geopolitical Tensions

Territorial disputes – e.g., South China Sea, India-China border, Israel-Palestine conflict.

Resource competition – oil, natural gas, rare earth minerals, and even water supplies.

Ideological differences – democracy vs. authoritarianism, capitalism vs. socialism.

Technological dominance – battles over 5G, semiconductors, and artificial intelligence.

Strategic influence – the U.S. vs. China in Asia-Pacific, Russia vs. NATO in Eastern Europe.

Geopolitical tensions may not always escalate into war, but they often manifest as economic weapons, including tariffs, sanctions, and restrictions on trade.

2. What Are Trade Wars?

Definition

A trade war is an economic conflict between nations where countries impose tariffs, quotas, or other trade barriers against each other, often in retaliation. Instead of cooperating in the free exchange of goods and services, they use trade as a weapon to gain leverage.

Mechanisms of Trade Wars

Tariffs – taxes on imported goods (e.g., U.S. tariffs on Chinese steel).

Quotas – limits on the number of goods imported (e.g., Japan’s rice import restrictions).

Subsidies – financial aid to domestic industries, making exports cheaper.

Export controls – restricting key goods, like semiconductors or defense equipment.

Sanctions – blocking trade altogether with specific countries or entities.

Difference Between Trade Dispute and Trade War

A trade dispute is usually limited and negotiable (resolved via WTO).

A trade war escalates into repeated rounds of retaliatory measures, often causing collateral damage to global supply chains.

3. Historical Background of Trade Wars

Mercantilism in the 16th–18th centuries – European powers imposed heavy tariffs and colonized territories to control resources.

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930, USA) – raised tariffs on over 20,000 goods, worsening the Great Depression.

Cold War Trade Restrictions (1947–1991) – U.S. and Soviet blocs limited economic interaction, fueling technological and arms races.

Japan-U.S. Trade Tensions (1980s) – disputes over Japanese car and electronics exports to the U.S. led to tariffs and voluntary export restraints.

U.S.-China Trade War (2018–present) – the most significant modern trade war, involving hundreds of billions in tariffs, sanctions, and tech restrictions.

4. Causes of Trade Wars in the Modern Era

Economic Protectionism – shielding domestic industries from foreign competition.

National Security Concerns – restricting sensitive technologies like 5G, AI, and semiconductors.

Geopolitical Rivalry – economic weapons as part of larger power struggles (e.g., U.S. vs. China, Russia vs. NATO).

Unfair Trade Practices Allegations – accusations of currency manipulation, IP theft, or dumping.

Populism & Domestic Politics – leaders use trade wars to appeal to local voters by promising to "bring jobs back home."

5. Case Study: The U.S.-China Trade War

The U.S.-China trade war (2018–present) is the most important example of how geopolitical rivalry shapes global trade.

Phase 1 (2018): U.S. imposed tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese goods, citing unfair trade practices and intellectual property theft.

Retaliation: China imposed tariffs on U.S. agricultural products, especially soybeans, targeting American farmers.

Escalation: Tariffs expanded to cover $360+ billion worth of goods.

Technology Restrictions: U.S. banned Huawei and restricted semiconductor exports.

Phase 1 Agreement (2020): China promised to increase U.S. imports, but tensions remain unresolved.

Impact:

Global supply chains disrupted.

Rising inflation due to higher import costs.

Shift of manufacturing from China to Vietnam, India, and Mexico.

U.S. farmers and Chinese exporters both suffered losses.

6. Geopolitical Hotspots Affecting Trade

1. Russia-Ukraine War

Western sanctions cut Russia off from global finance (SWIFT ban, oil & gas restrictions).

Europe shifted away from Russian energy, sparking energy crises.

Global wheat and fertilizer exports disrupted, raising food inflation worldwide.

2. Middle East Conflicts

Oil is a geopolitical weapon—any conflict in the Persian Gulf impacts global crude prices.

OPEC+ decisions are often politically influenced, affecting both producers and consumers.

3. South China Sea

A vital shipping lane ($3.5 trillion in trade passes annually).

Territorial disputes between China and Southeast Asian nations raise risks of blockades.

4. Taiwan & Semiconductors

Taiwan produces over 60% of global semiconductors (TSMC).

Any conflict over Taiwan could paralyze global tech supply chains.

5. India-China Border & Indo-Pacific Rivalries

India bans Chinese apps and tightens investment rules.

Strengthening of Quad alliance (US, India, Japan, Australia) reshapes Asian trade.

7. Impact of Geopolitical Tensions & Trade Wars

1. On Global Economy

Slower global growth due to reduced trade flows.

Inflationary pressures from higher tariffs and supply disruptions.

Increased uncertainty reduces foreign direct investment (FDI).

2. On Businesses

Supply chain realignments (China+1 strategy).

Rising costs of raw materials and logistics.

Technology companies face export bans and restrictions.

3. On Consumers

Higher prices for imported goods (electronics, fuel, food).

Limited choices in the market.

4. On Financial Markets

Stock market volatility increases.

Commodity prices (oil, gold, wheat) spike during conflicts.

Currency fluctuations as investors seek safe havens (USD, gold, yen).

5. On Developing Nations

Export-dependent economies suffer as global demand falls.

Some benefit by replacing disrupted supply chains (e.g., Vietnam, India, Mexico).

8. The Role of International Institutions

World Trade Organization (WTO)

Provides a platform to resolve disputes.

However, its influence has declined due to U.S.-China disputes and non-compliance.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) & World Bank

Provide financial stability during crises.

Encourage open trade but have limited enforcement power.

Regional Trade Agreements

CPTPP, RCEP, EU, USMCA act as counterbalances to global tensions.

Countries diversify trade partnerships to reduce dependence on rivals.

9. Strategies to Manage Geopolitical Risks

Diversification of Supply Chains – "China+1" strategy by multinationals.

Hedging Against Commodity Risks – futures contracts for oil, wheat, etc.

Regionalization of Trade – building self-sufficient trade blocs.

Technology Independence – countries investing in local semiconductor and AI industries.

Diplomacy & Dialogue – ongoing talks via G20, BRICS, ASEAN, and other forums.

10. The Future of Geopolitical Tensions & Trade Wars

Rise of Economic Nationalism: Countries prioritizing local industries over globalization.

Technology Wars Intensify: AI, semiconductors, and green energy will be new battlegrounds.

Fragmentation of Global Trade: Shift from globalization to "regionalization" or "friend-shoring."

Energy Transition Risks: Conflicts over rare earth metals, lithium, and cobalt needed for batteries.

New Alliances: BRICS expansion, Belt & Road Initiative, and Indo-Pacific strategies will reshape global economic influence.

Conclusion

Geopolitical tensions and trade wars are not temporary disruptions but structural features of the modern global economy. While globalization created interdependence, it also exposed vulnerabilities. Trade wars, sanctions, and economic blockades have become powerful tools of foreign policy, often with far-reaching economic consequences.

For businesses and investors, the challenge lies in navigating uncertainty through diversification, resilience, and adaptation. For policymakers, the task is to strike a balance between protecting national interests and sustaining global cooperation.

Ultimately, the world may not return to the hyper-globalization era of the early 2000s. Instead, we are moving toward a multipolar trade system shaped by regional blocs, strategic rivalries, and technological competition. How nations manage these tensions will determine the stability and prosperity of the 21st-century global economy.

US-China Trade War: Causes, Impacts, and Global ImplicationsHistorical Context of U.S.-China Economic Relations

Early Engagement

The United States normalized relations with China in 1979, following Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and China’s opening up to global markets.

Over the next three decades, U.S. companies moved manufacturing to China to take advantage of cheap labor and efficient supply chains.

China, in turn, gained access to advanced technologies, investment capital, and export markets.

Entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO)

In 2001, China’s entry into the WTO was a turning point. It marked its deeper integration into the global economy.

China rapidly grew into the “world’s factory,” and its exports surged.

However, the U.S. and other Western nations accused China of unfair practices: state subsidies, currency manipulation, forced technology transfers, and weak intellectual property protections.

The Growing Trade Imbalance

By the 2010s, the U.S. trade deficit with China exceeded $300 billion annually.

American policymakers began questioning whether trade with China was truly beneficial, especially as U.S. manufacturing jobs declined.

These tensions set the stage for a conflict that was as much about economics as it was about strategic rivalry.

The Outbreak of the Trade War (2018–2019)

Trump Administration’s Policies

In 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump labeled China as a “trade cheater,” accusing it of unfair practices.

By 2018, the U.S. imposed tariffs on steel, aluminum, and billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods.

China retaliated with tariffs on U.S. agricultural products, automobiles, and energy.

Escalation

By mid-2019, the U.S. had imposed tariffs on over $360 billion worth of Chinese imports, while China hit back with tariffs on $110 billion of U.S. goods.

The dispute extended beyond tariffs: restrictions were placed on Chinese technology firms like Huawei and ZTE.

Phase One Deal (2020)

After months of negotiations, the U.S. and China signed a “Phase One” trade deal in January 2020.

China pledged to purchase an additional $200 billion worth of U.S. goods and services over two years.

The deal addressed some issues like intellectual property and financial market access but left most tariffs in place.

Core Issues Driving the Trade War

Trade Imbalance

The U.S. imports far more from China than it exports, leading to a massive trade deficit.

While economists argue deficits are not inherently bad, politically they became a symbol of “unfairness.”

Intellectual Property (IP) Theft

American firms accused Chinese companies of copying technology and benefiting from weak IP protections.

Forced technology transfers—where U.S. firms had to share technology with Chinese partners as a condition for market entry—were a major point of contention.

State Subsidies and Industrial Policy

China’s state-driven model, including its “Made in China 2025” plan, aimed to dominate advanced industries like AI, robotics, and semiconductors.

The U.S. viewed this as a threat to its technological leadership.

National Security Concerns

The U.S. raised alarms over Chinese companies’ ties to the Communist Party, particularly in sectors like 5G, AI, and cybersecurity.

Huawei became a focal point, with Washington warning allies against using its equipment.

Geopolitical Rivalry

The trade war is also a battle for global leadership.

China’s rise threatens the U.S.-led order, prompting Washington to adopt a more confrontational stance.

Economic Impacts of the Trade War

On the United States

Consumers: Tariffs increased prices of everyday goods, from electronics to clothing, hurting U.S. households.

Farmers: China imposed tariffs on soybeans, pork, and other agricultural products, devastating American farmers who depended on Chinese markets.

Manufacturers: U.S. firms reliant on Chinese supply chains faced higher input costs.

GDP Impact: Estimates suggest the trade war reduced U.S. GDP growth by 0.3–0.5 percentage points annually.

On China

Export Decline: Chinese exports to the U.S. fell sharply, pushing firms to seek new markets.

Economic Slowdown: Growth dipped from above 6% to below 6%—the lowest in decades.

Technology Restrictions: Huawei and other tech giants faced disruptions in accessing U.S. chips and software.

Resilience: Despite the tariffs, China remained competitive due to diversified global markets and strong domestic consumption.

On the Global Economy

Supply Chains: The trade war disrupted global supply chains, prompting companies to diversify into countries like Vietnam, India, and Mexico.

Global Trade Growth: The WTO reported global trade growth slowed significantly in 2019 due to tensions.

Uncertainty: Businesses worldwide delayed investments amid fears of escalating tariffs and restrictions.

The Role of Technology and Decoupling

The trade war expanded into a tech war, especially in semiconductors, AI, and 5G.

Huawei Ban: The U.S. restricted Huawei from buying American components, pressuring allies to exclude Huawei from 5G networks.

Semiconductors: The U.S. tightened export controls on advanced chips, aiming to slow China’s technological rise.

Decoupling: Both nations began reducing dependency on each other, with companies shifting supply chains and governments investing in domestic industries.

This technological rivalry is often seen as the most critical and long-lasting element of the U.S.-China conflict.

Political Dimensions of the Trade War

Domestic Politics in the U.S.

The trade war became central to Trump’s political messaging, appealing to voters frustrated by globalization.

While tariffs hurt some sectors, they gained support among those seeking a tough stance on China.

Domestic Politics in China

China framed the trade war as foreign bullying, rallying nationalist sentiment.

The Communist Party emphasized self-reliance and doubled down on domestic technological innovation.

International Politics

Allies were caught in the middle:

Europe opposed Chinese trade practices but resisted U.S. pressure to take sides.

Developing nations saw opportunities as supply chains shifted.

COVID-19 and the Trade War

The pandemic, which began in China in late 2019, further complicated the trade war.

Supply Chain Shocks: COVID-19 highlighted global dependency on Chinese manufacturing for medical supplies, electronics, and more.

Geopolitical Blame: The U.S. accused China of mishandling the pandemic, worsening tensions.

Phase One Deal Collapse: China struggled to meet its purchase commitments due to the global recession.

In many ways, COVID-19 deepened the push toward decoupling and reshaping global trade patterns.

Global Implications of the US-China Trade War

Restructuring of Global Supply Chains

Companies are diversifying production away from China to reduce risks.

Southeast Asia, India, and Latin America are emerging as alternative hubs.

Impact on Global Institutions

The WTO struggled to mediate, highlighting weaknesses in the global trade system.

Calls for reforming trade rules to address issues like subsidies and digital trade gained momentum.

Pressure on Other Countries

Nations are forced to align with either the U.S. or China on issues like 5G, data security, and AI.

Middle powers like the EU, Japan, and Australia face tough choices in balancing relations.

Global Economic Slowdown

The IMF repeatedly warned that trade tensions could shave trillions off global GDP.

Slower global trade affects everything from commodity prices to investment flows.

Long-Term Outlook: Is the Trade War the New Normal?

The U.S.-China trade war represents more than a dispute over tariffs. It reflects a structural shift in global power dynamics.

Competition vs. Cooperation: While both countries remain economically interdependent, trust has eroded.

Persistent Rivalry: The Biden administration has largely continued Trump-era tariffs, indicating bipartisan consensus on confronting China.

Technology Cold War: The battle for dominance in semiconductors, AI, and 5G is set to intensify.

Partial Decoupling: Complete separation is unlikely, but critical sectors like technology, defense, and energy may increasingly operate in parallel ecosystems.

Conclusion

The U.S.-China trade war is one of the defining geopolitical and economic conflicts of the 21st century. What began as a tariff battle has evolved into a comprehensive strategic rivalry, encompassing trade, technology, national security, and global influence.

Both nations have paid economic costs, but the deeper impact lies in the reshaping of the global economy. Supply chains are being reorganized, trade institutions are under pressure, and countries around the world are recalibrating their positions between two superpowers.

Whether the future brings renewed cooperation or deepening confrontation depends on political will, economic necessity, and the evolving balance of power. What is clear, however, is that the trade war has fundamentally altered the trajectory of globalization and set the stage for decades of U.S.-China competition.

Role of Imports, Exports, and Tariffs Globally1. Understanding Imports

1.1 Definition and Importance

Imports refer to the goods and services that a country buys from foreign nations. They can include raw materials like crude oil, intermediate goods like steel, or finished consumer products like smartphones and luxury cars.

Imports are vital because no country is self-sufficient in everything. For example:

Japan imports crude oil because it lacks natural reserves.

India imports gold, electronics, and crude oil to meet domestic demand.

The U.S. imports cheap consumer goods from China and agricultural products from Latin America.

1.2 Role of Imports in Development

Imports help countries:

Access resources not available domestically (e.g., oil, rare earth minerals).

Improve quality of life by offering consumer choices.

Boost competitiveness by supplying industries with cheaper or better raw materials.

Promote innovation through exposure to foreign technology.

For example, many developing nations import advanced machinery to modernize their industries, which eventually helps them become competitive exporters.

1.3 Risks and Challenges of Imports

However, heavy reliance on imports can create vulnerabilities:

Trade deficits when imports exceed exports, leading to debt and currency depreciation.

Dependence on foreign suppliers can be risky during geopolitical tensions.

Loss of domestic jobs if foreign goods outcompete local industries.

A classic example is the U.S. steel industry, which suffered from cheap imports from China and other countries.

2. Understanding Exports

2.1 Definition and Importance

Exports are goods and services sold by one country to another. Exports are the lifeline of many economies, especially those with limited domestic markets.

For example:

Germany thrives on exports of automobiles and machinery.

China became the “world’s factory” by exporting electronics, textiles, and manufactured goods.

Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia rely on oil exports for government revenue.

2.2 Role of Exports in Growth

Exports contribute to:

Economic growth by earning foreign exchange.

Employment creation in manufacturing, agriculture, and services.

Technology transfer and skill development.

Trade balance improvement, reducing dependency on foreign debt.

Export-led growth has been a successful model for many Asian economies. South Korea, Taiwan, and later China built their prosperity on robust export sectors.

2.3 Risks and Challenges of Exports

Reliance on exports also carries risks:

Global demand fluctuations can hurt economies. For instance, oil-exporting nations face crises when oil prices fall.

Trade wars and tariffs can reduce access to markets.

Overdependence on one sector creates vulnerability (e.g., Venezuela relying heavily on oil).

3. Tariffs and Their Role in Global Trade

3.1 Definition and Purpose

Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported (and sometimes exported) goods. Governments use them to:

Protect domestic industries from foreign competition.

Generate revenue.

Influence trade balances.

Exercise political or economic leverage.

3.2 Types of Tariffs

Ad valorem tariffs: Percentage of the good’s value.

Specific tariffs: Fixed fee per unit.

Protective tariffs: Designed to shield local industries.

Revenue tariffs: Focused on government income.

3.3 Role of Tariffs in Trade Policy

Tariffs can:

Encourage domestic production by making imports more expensive.

Shape consumer preferences toward local products.

Serve as negotiation tools in international diplomacy.

However, tariffs often lead to trade wars. For example, the U.S.-China trade war (2018–2020) disrupted global supply chains, increased costs for consumers, and created uncertainty in markets.

4. Interconnection of Imports, Exports, and Tariffs

Imports, exports, and tariffs are deeply interconnected. Together they define a country’s trade balance and influence its global economic standing.

Countries that export more than they import run a trade surplus (e.g., Germany, China).

Countries that import more than they export run a trade deficit (e.g., the United States).

Tariffs can alter this balance:

High tariffs discourage imports but can provoke retaliatory tariffs, hurting exports.

Low tariffs encourage open trade but may harm domestic producers.

This interplay is at the heart of trade agreements, disputes, and organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO).

5. Historical Evolution of Global Trade

5.1 Mercantilism (16th–18th century)

Mercantilist policies emphasized maximizing exports and minimizing imports, with heavy reliance on tariffs. Colonial empires used this strategy to enrich themselves at the expense of colonies.

5.2 Industrial Revolution

Exports of manufactured goods surged from Europe to the world, while colonies provided raw materials. Imports fueled industrial growth, while tariffs protected nascent industries.

5.3 Post-World War II Liberalization

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later the WTO promoted free trade, reducing tariffs globally. Exports and imports flourished, creating the modern era of globalization.

5.4 21st Century Dynamics

Today’s global trade is shaped by:

Free trade agreements (e.g., NAFTA/USMCA, EU Single Market, RCEP).

Trade wars (e.g., U.S.-China).

Strategic tariffs to protect industries (e.g., solar panels, steel, agriculture).

6. Case Studies

6.1 China: Export Powerhouse

China’s rise is a textbook case of export-led growth. By keeping tariffs low, encouraging manufacturing, and integrating into global supply chains, China became the world’s largest exporter. However, its dependence on exports also made it vulnerable to U.S. tariffs in recent years.

6.2 United States: Import-Heavy Economy

The U.S. is the world’s largest importer, relying on foreign goods for consumer demand and industrial inputs. While this supports consumer affordability, it creates persistent trade deficits. The U.S. has used tariffs strategically to protect industries like steel and agriculture.

6.3 European Union: Balanced Trade

The EU maintains both strong exports (cars, pharmaceuticals, machinery) and imports (energy, raw materials). Its single market and common external tariffs demonstrate how regional integration manages trade collectively.

6.4 India: Emerging Economy

India imports heavily (crude oil, electronics, gold) but also pushes exports in IT services, pharmaceuticals, and textiles. Tariffs are frequently used to protect local farmers and small industries.

7. Benefits and Drawbacks of Free Trade vs. Protectionism

7.1 Free Trade Benefits

Efficiency and lower costs.

Greater consumer choices.

Encouragement of innovation.

Economic interdependence, reducing chances of conflict.

7.2 Protectionism Benefits

Protects infant industries.

Safeguards jobs.

Shields strategic sectors (defense, agriculture).

7.3 Risks of Each

Free trade can erode domestic industries.

Protectionism can lead to inefficiency and higher consumer costs.