Saudi’s $700 bln PIF is odd sort of sovereign fund

Barely a day goes by without an eye-catching story involving Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund. In the last few months alone, the $700 billion investor and the companies it controls have undertaken a landmark deal to revolutionise the world of golf, snapped up a $3.6 billion aircraft leasing business from Standard Chartered STAN, bought a 10% stake in Spanish telco Telefonica

TEF, and launched an audacious 300 million euro bid for the services of French soccer superstar Kylian Mbappé.

The PIF’s flamboyant investment style defies comparisons with other sovereign wealth funds. Multiple far-reaching targets make it difficult to tell whether the vehicle is achieving its goals. It’s also hard to judge how long it will keep throwing around cash on global markets.

HOME BIAS

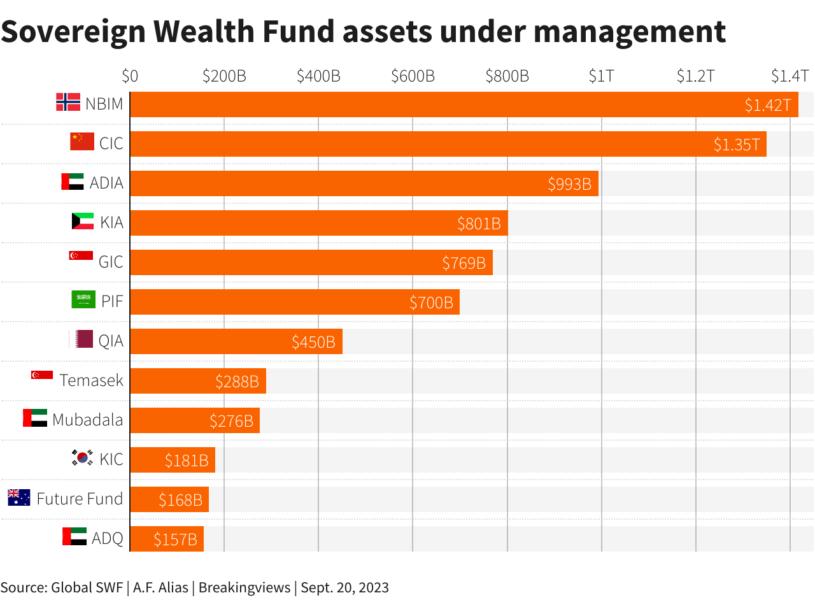

Sovereign wealth funds typically look like Norway’s $1.4 trillion Government Pension Fund Global or the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), which oversees nearly $1 trillion, according to analyst Global SWF. These juggernauts have been endowed by oil-rich governments to create national rainy-day funds that they prudently invest in overseas debt, equity and infrastructure.

The PIF is different. Founded in 1971, the fund was revamped in 2015 under the control of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), with a mandate to help deliver his Vision 2030 plan to diversify the kingdom’s oil-dependent economy and create private sector jobs for its 32 million people.

PIF Governor Yasir Al-Rumayyan does not receive a predetermined flow of oil wealth from the state, but instead has been handed a portfolio of domestic and international assets. A third of the fund consists of significant stakes in domestic companies like the $51 billion Saudi Telecom Company 7010 and $53 billion Saudi National Bank

1180. It also controls 8% of $2.2 trillion oil giant Saudi Aramco 663WB, worth about $180 billion, which Riyadh transferred in 2022 and earlier this year. A fifth of all PIF assets in 2022 were targeted at developing new industries like gaming, while another 5% was earmarked for giga-projects like the $500 billion NEOM, home of “The Line” – a futuristic 110-mile long “linear smart city”.

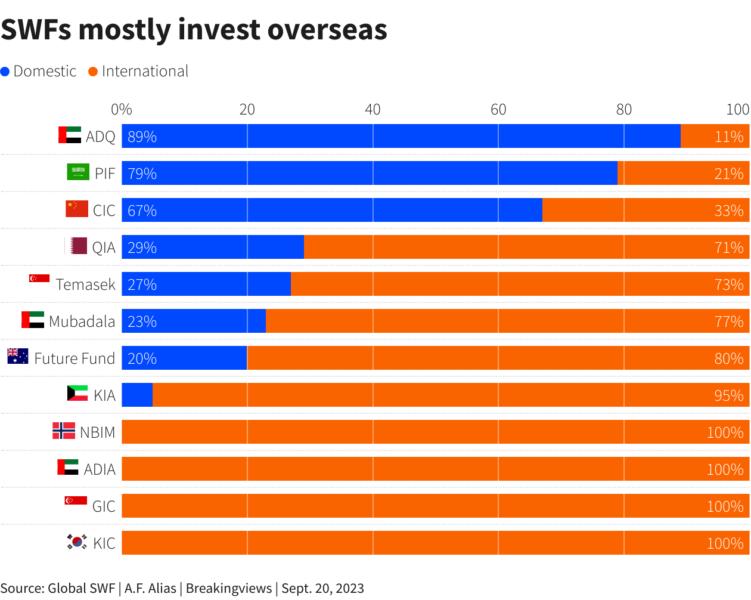

Despite its image as a serial acquirer of high-profile western trinkets, the PIF only deployed 21% of its assets outside the kingdom in 2022. By comparison, funds like the Qatar Investment Authority, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala and Singapore’s Temasek invest only about a quarter of their wealth at home, according to Global SWF.

The PIF’s investment strategy is also racier than its more conservative peers. In a podcast recorded in October last year, Al-Rumayyan recounted how he, MbS and senior PIF managers lobbied Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz to take a $35 billion punt on depressed western stocks during the Covid-19 pandemic – overruling the objections of politicians on the fund’s board. The bet paid off as the initial outlay quickly swelled to $49 billion. But the episode reinforces the impression that the PIF is a mix of venture capital, hedge fund and startup money.

BLURRED LINES

The PIF already has some high-profile goofs under its belt. The most spectacular was probably handing $45 billion to SoftBank Group 9984 boss Masayoshi Son for his $100 billion first Vision Fund. As of March the Japanese investor’s splurge on high-profile tech bets, including office-sharing flop WeWork, had generated a meagre 3% internal rate of return for limited partners like the PIF since inception, even though a chunk of the cash was in coupon-paying preferred shares. Saudi National Bank lost a packet on Credit Suisse when UBS

UBSG rescued the Swiss lender earlier this year.

The PIF’s hyper-ambitious mandate makes such screw-ups more likely. Yet overall it isn’t doing especially badly. In 2021 it made a 25% total shareholder return. As markets tumbled in 2022 it suffered a 6.5% loss, though this was in line with the 5.5% hit recorded by SWFs in general, according to Global SWF.

Even so, the PIF’s goal of advancing Saudi diversification complicates any assessment. The fund says it will focus on 13 “strategic sectors”, covering almost everything except oil. Any credible valuation for NEOM and three other Saudi giga-projects will depend on major international investors buying in. But the kingdom remains way off its target of attracting $100 billion of foreign direct investment by 2030. In 2022 it received only $8 billion.

TREBLE VISION

The PIF’s goal to boost its assets under management to $2 trillion is also odd. If the fund keeps earning the same 8% average annual return it has managed since 2018 its assets would reach $1.3 trillion by that date, according to Breakingviews calculations. To get to $2 trillion under its own steam, it would need to generate a steep 14% annual return for the rest of the decade.

Al-Rumayyan could raise cash by selling further chunks of the PIF’s corporate holdings. In recent years it has offloaded stakes in Saudi Telecom Company, the Tadawul stock exchange and gas company GASCO. Another option is to borrow. At about $25 billion, the PIF’s net debt is currently less than 5% of its assets.

Then there are potential transfers from the state. Al-Rumayyan could for example receive more of the $19.5 billion quarterly dividend Aramco hands to investors including the government, which holds 90%.

The other option is to plonk more Aramco shares in the PIF, swelling its assets, boosting its income, and making it a more creditworthy borrower. The oil giant can also help in other ways, such as when it spent $69 billion on the PIF’s 70% stake in chemicals group SABIC 2010 in 2020. Al-Rumayyan has some influence over these transactions as he also chairs Aramco.

Tot it all up, and it’s possible to see the PIF reaching MbS’s target. To steer the Saudi economy away from oil, however, the PIF will need more investments in nascent industries such as its new electric vehicle joint venture with Taiwan’s Foxconn 2317.

Whether that rosy vision materialises is anyone’s guess. While rival states top up their rainy-day funds, the PIF could be a powerful force for diversifying the Saudi economy – or an ATM to prop up a cash-strapped government. Either way, it will be a sovereign wealth fund in name only.

Follow @gfhay and @karenkkwok on X

CONTEXT NEWS

The Public Investment Fund’s assets under management surpassed 2.2 trillion riyals ($594 billion) in 2022, according to its annual report published on Aug. 6, compared with 1.98 trillion riyals for 2021. Factoring in the recent transfer by the government of a 4% stake in oil giant Saudi Aramco, the PIF’s AUM are now around $700 billion, according to analyst Global SWF.

The kingdom's sovereign wealth fund generated a total annual shareholder return of 8% for the five years up to 2022, and established 25 companies in that year. In the same year it deployed 120 billion riyals in domestic strategic sectors.

The fund said 17% of its assets were managed externally, with 83% managed internally.