Gold vs. Equities — The 45-Year Cycle and a Pending Monetary Reset

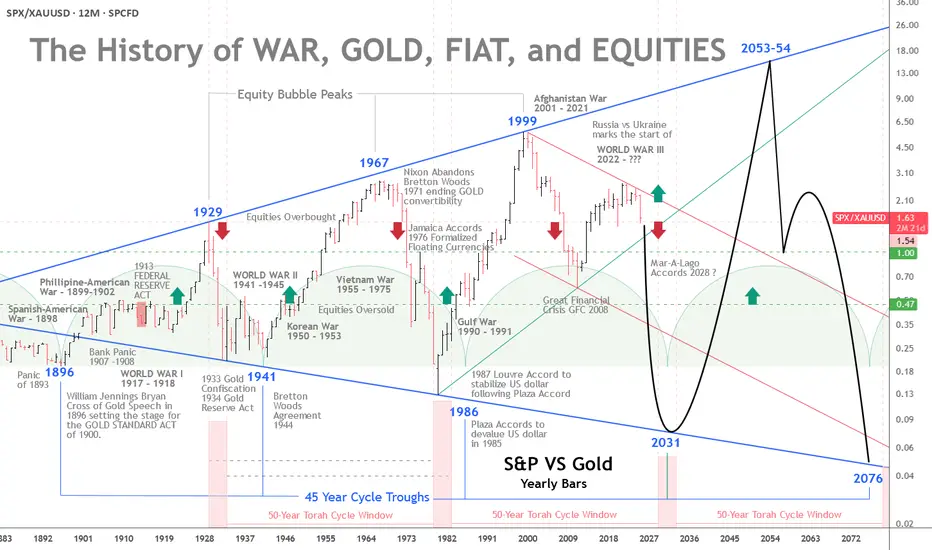

The interplay of war, gold, fiat money, and equities has long been a barometer of real wealth and economic stability. A recurring pattern emerges across modern history: approximately 45-year intervals when gold strengthens relative to equities.

From the Panic of 1893 to the present, these cycles have coincided with major monetary shifts and geopolitical shocks.

With a broadening 100-year pattern, rising geopolitical tension, and roughly $300 trillion in global debt, a monetary reset by the early 2030s is plausibly on the horizon.

The 45-Year Cycle — Gold’s Strength at Equity Troughs

The pattern’s first trough is traced to 1896, when William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech preceded the Gold Standard Act of 1900. Equities were weak after the Panic of 1893, and gold gained prominence. Thirteen years later, the Federal Reserve would be created. More on the 45-year cycle later.

The 50-Year Jubilee Cycle

The Torah’s 50-year Jubilee cycle, as outlined in Leviticus 25:8–12, is a profound economic and social reset that follows seven 7-year Shemitah cycles, totaling 49 years, with the 50th year designated as the Jubilee.

Each Shemitah cycle concludes with a sabbatical year (year 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49), during which the land rests, debts are released, and economic imbalances are addressed (Leviticus 25:1–7).

The Jubilee, occurring in the 50th year, amplifies this reset by mandating the return of ancestral lands, freeing of slaves, and further debt forgiveness, symbolizing a divine restoration of societal equity.

While built on the 49-year framework of seven Shemitahs, the 50th year stands distinct, marking a transformative culmination rather than a simple extension of the Shemitah cycle.

The five-year Jubilee windows highlighted at the base of the chart compliment the 45-year cycles previously noted. The 4 year Jubilee windows are projected from the roaring 20s peak in 1929 and the 1932 bear market low four years later.

The next Jubilee window is scheduled to occur some time between 2029 and 2031.

The Panic of 1907 and the Fed

The Panic of 1907 was a severe crisis, with bank runs, failing trust companies, and a liquidity crunch centered in New York. The collapse of copper speculators (F. Augustus Heinze and Charles W. Morse) triggered runs on institutions like the Knickerbocker Trust.

Private bankers led by J.P. Morgan injected liquidity (over $25 million) to stabilize the system. The shock exposed the absence of a lender of last resort and precipitated reforms.

Congress responded with the Aldrich–Vreeland Act (1908) and the National Monetary Commission, whose 1911 report recommended a central bank to supply “elastic currency.”

After debate and hearings, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913, creating a decentralized central bank with 12 regional banks.

Some alternative accounts (e.g., The Creature from Jekyll Island) argue that the panic was exploited to centralize financial control. Mainstream history, however, treats the panic as the genuine catalyst for reform.

Whatever the intent, the Fed’s creation shifted the tools available to manage crises—and, over time, central banks have played an instrumental role in financing wars and expanding Fiat currency.

The Fed and World War I

World War I began in Europe in 1914 (U.S. entry in 1917). The Fed began operations in November 1914 and later supported wartime financing by:

Although the Fed was created primarily to prevent panics and stabilize banking, its early role in war finance shifted expectations about central banking’s functions.

From Confiscation to Bretton Woods to the Nixon Shock

In 1933, during the Great Depression, the U.S. effectively nationalized gold—private ownership was outlawed, and the official price was later reset at $35/oz by the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. Private ownership remained restricted until President Ford legalized it again in 1974.

World War II and the Bretton Woods Agreement (1944) cemented gold’s role: the dollar became the anchor of the system, and other currencies pegged to it.

That status persisted until August 15, 1971, when President Nixon suspended dollar-gold convertibility—the “Nixon Shock”—moving the world toward fiat currencies.

The Petrodollar and Post-1971 Arrangements

After 1971, the U.S. worked to preserve dollar demand. The petrodollar system emerged in the early 1970s: following the 1973 oil shock, a U.S.–Saudi understanding (1974) helped ensure oil continued to be priced in dollars and that oil revenues were recycled into U.S. Treasuries—supporting the dollar’s global role despite its fiat status.

Devaluations, Floating Rates, and the End of Bretton Woods

Two formal “devaluations” followed the Nixon Shock:

These moves were reactive attempts to adjust the dollar’s value amid trade deficits, inflation, and speculative pressures. They ultimately ushered in a fiat era, where market forces, not official pegs, set the price of gold.

Triffin’s Dilemma — Then and Now

Triffin’s Dilemma describes the structural tension faced by a reserve currency issuer: it must supply enough currency to ensure global liquidity (running deficits) while risking domestic instability and a loss of confidence.

Britain faced this under the gold standard; the U.S. faced it under Bretton Woods and again after 1971, albeit in a different form.

Modern manifestations include inflation, persistent fiscal and external deficits, and mounting debt. International policy coordination (e.g., the Plaza and Louvre Accords) repeatedly tried—and only partially succeeded—to manage these tensions.

The Plaza (1985) and Louvre (1987) Accords

Both accords illustrate the extreme difficulty in balancing global liquidity needs with domestic economic health in a fiat system.

De-industrialization, Bubbles, and the Broadening Pattern

Orthodox history would argue that U.S. de-industrialization in the 1990s was rational at the time. Globalization and cost arbitrage provided short-term benefits, but they increased trade deficits, foreign dependency, and robbed the middle class of high-paying jobs. That loss of capacity heightens vulnerability to dollar shocks and complicates any re-industrialization efforts today.

Measured in gold, equities have experienced expanding ranges:

From 1999, relative equity values fell until a trough around 2011 (coinciding with the European debt crisis). Quantitative easing and policy responses (2010 onward) restored growth, but frailties remained (e.g., repo market stress in 2018).

COVID produced another shock; aggressive fiscal and monetary responses engineered a V-shaped asset recovery but also higher inflation.

Relative to gold, equities peaked in 1999 and have trended lower since. As nominal stock prices register all-time-highs in dollars—fueled by AI and other themes—equities are historically overvalued. When priced against gold, the apparent bubble in nominal terms looks more like an extended bear market ready for its next down-leg.

The Broadening Pattern and the Next Trough

A broadening pattern illustrates the gold equity ratio range expanding with each major peak and trough. If we accept a roughly 45-year rhythm from the 1980/86 period, the next cyclical trough may fall between 2025 and 2031, with 2031 a focal point. Whether this manifests as a runaway gold price, a sharp equity collapse, or both remains uncertain.

If a sovereign-debt crisis or major war escalates, changes could accelerate—some scenarios even speculate about a negotiated new monetary framework (e.g., “Mar-A-Lago Accords”) in the next 5–15 years.

Geopolitics and the $300 Trillion Debt

Geopolitical tension compounds financial stress. The Russia-Ukraine war, plausibly the start of World War III, NATO involvement, and nuclear saber-rattling evoke systemic risk. Global debt—estimated at around $300 trillion (over 300% of GDP per the Institute of International Finance)—is unsustainable.

U.S. public debt (~$38 trillion) now carries interest costs comparable to defense spending.

Central bank money creation to service debt erodes confidence in fiat currencies and boosts demand for gold. Historical monetary resets (Bretton Woods, Nixon Shock) followed similar pressures of debt and conflict.

A modern reset could push gold well beyond current records—potentially into the high thousands or five-figure territory if confidence collapses.

Implications of a Pending Monetary Reset

A reset might take various forms:

Given Triffin’s Dilemma, inflated financial assets, and interconnected global linkages, a modern reset could be far larger in scale and speed than past adjustments. Assets, trade, and supply chains are far larger and more intertwined than in 1971, increasing contagion risk.

Practical takeaway: investors should consider gold’s role in portfolios; policymakers must confront debt sustainability or risk a market-driven reckoning that could disrupt global finance.

Conclusion

Triffin’s Dilemma, decades of accumulated imbalances, de-industrialization, and escalating geopolitical risk suggest a monetary reset is plausible between 2030 and 2035—possibly sooner under severe stress.

A modern reset would be more disruptive than past episodes because today’s global economy is larger, more integrated, and technologically complex. The question is not only whether such a reset will occur, but how policymakers and markets will manage it.

The stakes—global financial stability and the relative value of fiat versus real assets—could not be higher.

The interplay of war, gold, fiat money, and equities has long been a barometer of real wealth and economic stability. A recurring pattern emerges across modern history: approximately 45-year intervals when gold strengthens relative to equities.

From the Panic of 1893 to the present, these cycles have coincided with major monetary shifts and geopolitical shocks.

With a broadening 100-year pattern, rising geopolitical tension, and roughly $300 trillion in global debt, a monetary reset by the early 2030s is plausibly on the horizon.

The 45-Year Cycle — Gold’s Strength at Equity Troughs

The pattern’s first trough is traced to 1896, when William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech preceded the Gold Standard Act of 1900. Equities were weak after the Panic of 1893, and gold gained prominence. Thirteen years later, the Federal Reserve would be created. More on the 45-year cycle later.

The 50-Year Jubilee Cycle

The Torah’s 50-year Jubilee cycle, as outlined in Leviticus 25:8–12, is a profound economic and social reset that follows seven 7-year Shemitah cycles, totaling 49 years, with the 50th year designated as the Jubilee.

Each Shemitah cycle concludes with a sabbatical year (year 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49), during which the land rests, debts are released, and economic imbalances are addressed (Leviticus 25:1–7).

The Jubilee, occurring in the 50th year, amplifies this reset by mandating the return of ancestral lands, freeing of slaves, and further debt forgiveness, symbolizing a divine restoration of societal equity.

While built on the 49-year framework of seven Shemitahs, the 50th year stands distinct, marking a transformative culmination rather than a simple extension of the Shemitah cycle.

The five-year Jubilee windows highlighted at the base of the chart compliment the 45-year cycles previously noted. The 4 year Jubilee windows are projected from the roaring 20s peak in 1929 and the 1932 bear market low four years later.

The next Jubilee window is scheduled to occur some time between 2029 and 2031.

Returning to History and the 45-Year Cycles:

The Panic of 1907 and the Fed

The Panic of 1907 was a severe crisis, with bank runs, failing trust companies, and a liquidity crunch centered in New York. The collapse of copper speculators (F. Augustus Heinze and Charles W. Morse) triggered runs on institutions like the Knickerbocker Trust.

Private bankers led by J.P. Morgan injected liquidity (over $25 million) to stabilize the system. The shock exposed the absence of a lender of last resort and precipitated reforms.

Congress responded with the Aldrich–Vreeland Act (1908) and the National Monetary Commission, whose 1911 report recommended a central bank to supply “elastic currency.”

After debate and hearings, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913, creating a decentralized central bank with 12 regional banks.

Some alternative accounts (e.g., The Creature from Jekyll Island) argue that the panic was exploited to centralize financial control. Mainstream history, however, treats the panic as the genuine catalyst for reform.

Whatever the intent, the Fed’s creation shifted the tools available to manage crises—and, over time, central banks have played an instrumental role in financing wars and expanding Fiat currency.

The Fed and World War I

World War I began in Europe in 1914 (U.S. entry in 1917). The Fed began operations in November 1914 and later supported wartime financing by:

- Marketing Liberty Bonds (~$21.5 billion raised, 1917–1919).

- Providing low-interest loans to banks buying Treasury securities (via 1916-era amendments).

- Expanding the money supply, which contributed to wartime inflation.

Although the Fed was created primarily to prevent panics and stabilize banking, its early role in war finance shifted expectations about central banking’s functions.

From Confiscation to Bretton Woods to the Nixon Shock

In 1933, during the Great Depression, the U.S. effectively nationalized gold—private ownership was outlawed, and the official price was later reset at $35/oz by the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. Private ownership remained restricted until President Ford legalized it again in 1974.

World War II and the Bretton Woods Agreement (1944) cemented gold’s role: the dollar became the anchor of the system, and other currencies pegged to it.

That status persisted until August 15, 1971, when President Nixon suspended dollar-gold convertibility—the “Nixon Shock”—moving the world toward fiat currencies.

The Petrodollar and Post-1971 Arrangements

After 1971, the U.S. worked to preserve dollar demand. The petrodollar system emerged in the early 1970s: following the 1973 oil shock, a U.S.–Saudi understanding (1974) helped ensure oil continued to be priced in dollars and that oil revenues were recycled into U.S. Treasuries—supporting the dollar’s global role despite its fiat status.

Devaluations, Floating Rates, and the End of Bretton Woods

Two formal “devaluations” followed the Nixon Shock:

- Smithsonian Agreement (Dec 18, 1971): Raised the official gold price from $35 to $38/oz (an 8.57% change) as a stopgap attempt to stabilize fixed rates without restoring convertibility. It widened exchange banding but proved unsustainable.

- On February 12, 1973, the official gold price was revalued to $42.22/oz (roughly a 10% change), a symbolic acknowledgment that Bretton Woods was collapsing. By March 1973, major economies had effectively moved to floating exchange rates, and market gold prices surged.

These moves were reactive attempts to adjust the dollar’s value amid trade deficits, inflation, and speculative pressures. They ultimately ushered in a fiat era, where market forces, not official pegs, set the price of gold.

Triffin’s Dilemma — Then and Now

Triffin’s Dilemma describes the structural tension faced by a reserve currency issuer: it must supply enough currency to ensure global liquidity (running deficits) while risking domestic instability and a loss of confidence.

Britain faced this under the gold standard; the U.S. faced it under Bretton Woods and again after 1971, albeit in a different form.

Modern manifestations include inflation, persistent fiscal and external deficits, and mounting debt. International policy coordination (e.g., the Plaza and Louvre Accords) repeatedly tried—and only partially succeeded—to manage these tensions.

The Plaza (1985) and Louvre (1987) Accords

- Plaza Accord (Sept 22, 1985): G5 nations coordinated to depreciate the dollar (it had appreciated ~50% since 1980). The goal was to ease U.S. trade imbalances. The dollar fell substantially vs. the yen and mark by 1987.

- Louvre Accord (Feb 22, 1987): G6 sought to stabilize the dollar after its rapid decline following the Plaza Accord, setting informal target zones and coordinating intervention. It temporarily checked volatility but did not solve underlying imbalances.

Both accords illustrate the extreme difficulty in balancing global liquidity needs with domestic economic health in a fiat system.

De-industrialization, Bubbles, and the Broadening Pattern

Orthodox history would argue that U.S. de-industrialization in the 1990s was rational at the time. Globalization and cost arbitrage provided short-term benefits, but they increased trade deficits, foreign dependency, and robbed the middle class of high-paying jobs. That loss of capacity heightens vulnerability to dollar shocks and complicates any re-industrialization efforts today.

Measured in gold, equities have experienced expanding ranges:

- Equity peaks (1929, 1967, 1999) were followed by troughs where gold outperformed (1896, 1941, 1980/86).

- Gold peaked in 1980, even though the cyclical trough in the broader pattern was nearer 1986—showing that cycles can shift.

- The dot-com peak (1999) marked a secular low for gold relative to equities. The ensuing crashes, 9/11, and the War in Afghanistan, followed by the 2008–2009 Financial Crisis (GFC), moved markets profoundly—both nominally and in terms of gold.

From 1999, relative equity values fell until a trough around 2011 (coinciding with the European debt crisis). Quantitative easing and policy responses (2010 onward) restored growth, but frailties remained (e.g., repo market stress in 2018).

COVID produced another shock; aggressive fiscal and monetary responses engineered a V-shaped asset recovery but also higher inflation.

Relative to gold, equities peaked in 1999 and have trended lower since. As nominal stock prices register all-time-highs in dollars—fueled by AI and other themes—equities are historically overvalued. When priced against gold, the apparent bubble in nominal terms looks more like an extended bear market ready for its next down-leg.

The Broadening Pattern and the Next Trough

A broadening pattern illustrates the gold equity ratio range expanding with each major peak and trough. If we accept a roughly 45-year rhythm from the 1980/86 period, the next cyclical trough may fall between 2025 and 2031, with 2031 a focal point. Whether this manifests as a runaway gold price, a sharp equity collapse, or both remains uncertain.

If a sovereign-debt crisis or major war escalates, changes could accelerate—some scenarios even speculate about a negotiated new monetary framework (e.g., “Mar-A-Lago Accords”) in the next 5–15 years.

Geopolitics and the $300 Trillion Debt

Geopolitical tension compounds financial stress. The Russia-Ukraine war, plausibly the start of World War III, NATO involvement, and nuclear saber-rattling evoke systemic risk. Global debt—estimated at around $300 trillion (over 300% of GDP per the Institute of International Finance)—is unsustainable.

U.S. public debt (~$38 trillion) now carries interest costs comparable to defense spending.

Central bank money creation to service debt erodes confidence in fiat currencies and boosts demand for gold. Historical monetary resets (Bretton Woods, Nixon Shock) followed similar pressures of debt and conflict.

A modern reset could push gold well beyond current records—potentially into the high thousands or five-figure territory if confidence collapses.

Implications of a Pending Monetary Reset

A reset might take various forms:

- A partial return to a gold-linked standard, perhaps supplemented by tokenized/digital assets.

- Forced debt restructuring or coordinated global defaults.

- Rapid adoption of digital currencies (including state-issued tokens—CBDCs) as part of a new settlement architecture.

Given Triffin’s Dilemma, inflated financial assets, and interconnected global linkages, a modern reset could be far larger in scale and speed than past adjustments. Assets, trade, and supply chains are far larger and more intertwined than in 1971, increasing contagion risk.

Practical takeaway: investors should consider gold’s role in portfolios; policymakers must confront debt sustainability or risk a market-driven reckoning that could disrupt global finance.

Conclusion

The Torah's 50-year Jubilee, the 45-year cycle and the century-long broadening pattern suggest we are approaching a structural turning point.

Triffin’s Dilemma, decades of accumulated imbalances, de-industrialization, and escalating geopolitical risk suggest a monetary reset is plausible between 2030 and 2035—possibly sooner under severe stress.

A modern reset would be more disruptive than past episodes because today’s global economy is larger, more integrated, and technologically complex. The question is not only whether such a reset will occur, but how policymakers and markets will manage it.

The stakes—global financial stability and the relative value of fiat versus real assets—could not be higher.

Note

NOTE: Gold peaked in 1980, even though the 45-year cyclical equity trough in the broader pattern was nearer 1986—showing that cycles can shift. The 50-year Jubilee cycle captures the 1980 inflection point with far better precision.Disclaimer

The information and publications are not meant to be, and do not constitute, financial, investment, trading, or other types of advice or recommendations supplied or endorsed by TradingView. Read more in the Terms of Use.

Disclaimer

The information and publications are not meant to be, and do not constitute, financial, investment, trading, or other types of advice or recommendations supplied or endorsed by TradingView. Read more in the Terms of Use.