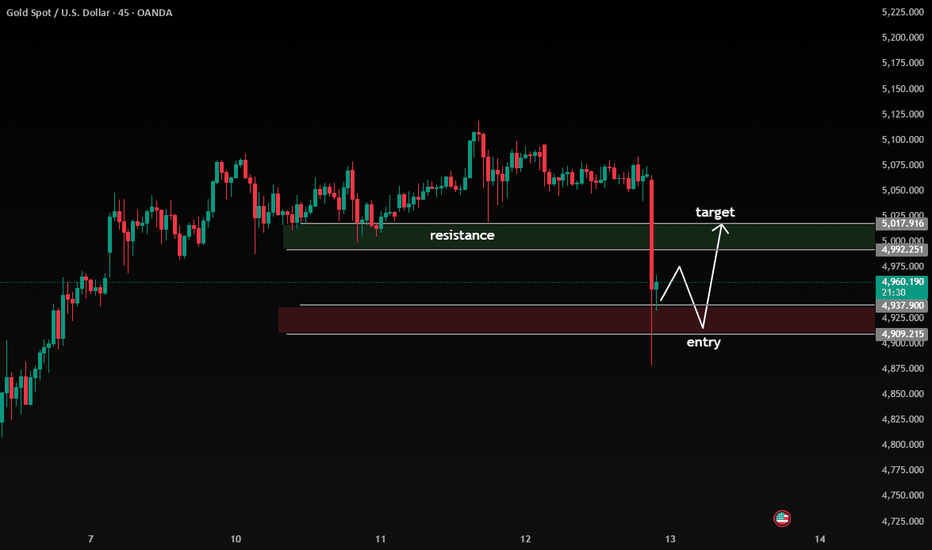

Bearish Breakout Below Range, Pullback Into Resistance

Current Structure:

Price was ranging under a clear resistance zone (≈ 4,992 – 5,018) before printing a strong bearish impulse candle that decisively broke structure to the downside. This move invalidated short-term bullish momentum and shifted bias intraday to bearish.

🔎 Key Observations

1. Market Structure Shift

The large bearish candle confirms a break of minor support and signals momentum expansion.

This looks like a liquidity sweep + displacement move, often followed by a corrective pullback.

2. Entry Zone (Demand) – 4,909 – 4,937

Price tapped into a marked demand/support area.

Reaction here suggests potential for a short-term retracement rather than immediate continuation.

This zone is likely where buyers attempt a bounce.

3. Resistance / Target Zone – 4,992 – 5,018

Previous consolidation + supply area.

If price retraces, this zone becomes:

A sell-on-rally area

A potential lower high formation zone

📈 Probable Scenario (Based on Structure)

Most likely flow:

Short-term bounce from demand

Retracement toward ~4,975–5,000

Rejection at resistance

Continuation lower if bearish structure holds

This would form a lower high, confirming bearish continuation.

⚠️ Alternative Scenario

If price:

Reclaims and closes strongly above 5,018

Holds above resistance

Then the bearish impulse becomes a fake breakdown and buyers regain control.

📊 Bias Summary

Intraday Bias: Bearish

Short-term Expectation: Pullback → rejection → continuation lower

Invalidation: Sustained move above resistance zone

Forextargets

Rejection at Resistance, Short Setup Toward Mid-Range Support Overview

On the 45-minute timeframe, Gold is trading within a broader range structure:

Major Support Zone: 4,600 – 4,670 (strong demand base)

Mid-Range Support / Target Zone: ~4,880 – 4,920

Major Resistance Zone: 5,100 – 5,150 (supply area)

Price recently rallied from the lower support zone (~4,600 area), formed a higher low, and pushed back into the key resistance region around 5,100.

📈 Current Price Action

Price tapped into the 5,100–5,150 resistance zone

Rejection wick and pullback forming

Momentum appears to be slowing near supply

Structure suggests possible lower high formation on this timeframe

This area has previously acted as a distribution zone, making it technically significant.

🎯 Trade Idea Illustrated on Chart

Bias: Short (counter-move within range)

Entry: Near 5,100–5,120 resistance after confirmation (rejection / bearish candle close)

Target: 4,880–4,920 mid-range support zone

Extended Target (if breakdown continues): 4,650 major support

🧠 Why This Setup Makes Sense

Price is reacting at a proven resistance area.

Market is still broadly ranging (not clean breakout structure).

Risk-to-reward favors shorting near supply rather than buying into resistance.

Mid-range inefficiency/support provides a logical first take-profit level.

⚠️ Invalidation

Strong breakout and 45m close above 5,150

Follow-through bullish momentum with acceptance above resistance

If that happens, structure shifts toward continuation rather than rejection.

📌 Summary

Gold is testing a key resistance zone inside a larger range. The chart suggests a potential rejection and pullback toward the 4,900 region before any larger directional decision.

45-Minute Chart Analysis: Support Hold → Range Break Attempt

Market Structure

Price previously sold off hard into the major demand/support zone (~4,650–4,720).

That support held cleanly (strong rejection + momentum shift), kicking off a rounded recovery / corrective arc.

Since Feb 7–10, price has been consolidating above a minor demand zone (~5,000–5,020) — classic base-building behavior.

Key Levels

Major Support (blue zone below): ~4,650–4,720

→ Strong institutional demand, validated by multiple reactions.

Current Entry Zone (blue box): ~5,000–5,020

→ Prior resistance turned support + consolidation range.

Major Resistance (gray zone): ~5,180–5,220

→ Supply zone / previous distribution area.

Trade Idea Logic

The chart is showing a higher low + compression under resistance.

If price holds above the entry zone and prints bullish continuation (strong close, volume expansion), the probability favors a push into resistance.

The drawn arrow reflects a range expansion move, not a breakout confirmation yet.

Bias

Bullish continuation (conditional) while price holds above ~5,000.

A clean rejection below the entry zone would invalidate the setup and shift bias back to range or pullback.

Summary

This is a support-hold → consolidation → resistance-target structure.

Patience matters here: confirmation above the range is the green light 🚦, while losing the blue entry zone is the warning sign.

Global Crash Alert: Market Meltdown1. Macroeconomic Stress and Inflation Pressures

One of the primary triggers of the current market turmoil is the persistent macroeconomic instability observed globally. Central banks, particularly in advanced economies, have been grappling with elevated inflation levels that have persisted longer than expected. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve's aggressive interest rate hikes to curb inflation have raised borrowing costs, putting pressure on both consumers and corporations. Higher interest rates slow economic growth by reducing spending and investment, which can trigger declines in corporate earnings and, consequently, stock valuations.

Emerging markets are not immune either. Many countries are facing stagflation-like conditions, where inflation remains high despite slowing economic growth. The combination of weakening currencies, rising debt servicing costs, and constrained fiscal space creates vulnerabilities that can quickly translate into capital flight, stock market declines, and a regional financial crisis.

2. Debt Overhang and Financial Leverage

High levels of global debt, particularly in corporate and sovereign sectors, exacerbate the risk of a market meltdown. Companies that borrowed aggressively during low-interest-rate periods are now struggling with refinancing costs amid rising rates. Similarly, countries with high external debt obligations face mounting pressure as currency depreciations increase the real cost of debt repayment.

Financial leverage amplifies market volatility. Hedge funds, institutional investors, and retail traders using borrowed capital may be forced to liquidate positions in a falling market, creating a cascading effect of sell-offs. This deleveraging spiral can accelerate a market crash, causing liquidity shortages and triggering panic across multiple asset classes.

3. Geopolitical Risks and Supply Chain Disruptions

Geopolitical tensions have reached levels that directly impact global financial stability. Conflicts in key regions, trade wars, and sanctions create uncertainty, disrupting supply chains, energy markets, and commodity prices. For instance, ongoing tensions in energy-producing regions can spike oil and gas prices, contributing to inflationary pressures and reducing corporate profitability.

Supply chain bottlenecks, which have persisted since the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbate inflation and create unpredictability in earnings forecasts. Investors respond negatively to uncertainty, often selling equities and other risk assets, which intensifies market declines.

4. Investor Sentiment and Behavioral Triggers

Markets are not purely driven by fundamentals; investor psychology plays a critical role in amplifying volatility. Fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) can spread rapidly in today’s hyperconnected financial world, where social media and instant news updates influence decisions.

A market meltdown is often self-reinforcing: initial losses trigger margin calls and forced selling, which leads to further declines and heightened panic. Retail investors, driven by fear of losses, may exit positions en masse, while institutional players attempt to reduce risk exposure, further accelerating the crash.

5. Correlation and Contagion Effects

One of the defining characteristics of modern financial crises is the high degree of market interconnectivity. A crisis in one major economy can quickly spill over to others, as global investors adjust portfolios to mitigate risk. For instance, a sharp downturn in U.S. equities often leads to capital outflows from emerging markets, currency depreciation, and rising yields on sovereign debt.

Similarly, interlinked derivatives markets, credit default swaps, and highly leveraged financial instruments can magnify losses. In a worst-case scenario, this interconnectedness could lead to a systemic crisis affecting banks, hedge funds, pension funds, and insurance companies simultaneously.

6. Early Warning Indicators

Several indicators point toward an elevated risk of a global market meltdown. Equity markets are showing increased volatility, with major indices hitting technical support levels that historically coincide with panic selling. Credit spreads are widening, signaling higher default risk and investor caution. Bond yields are rising in many economies, reflecting fears of persistent inflation and tighter monetary policy.

Additionally, global liquidity conditions are tightening as central banks withdraw pandemic-era stimulus measures. Reduced liquidity makes markets more sensitive to shocks, increasing the likelihood of rapid price declines and severe corrections.

7. Potential Implications

The consequences of a global market meltdown would be profound. A severe crash in equity markets could erode trillions of dollars in wealth, reducing consumer confidence and spending. Corporate bankruptcies could rise as financing becomes scarce, leading to layoffs, wage stagnation, and economic contraction. Sovereign debt crises in vulnerable countries could trigger regional instability, forcing international intervention.

Financial institutions may face solvency challenges, particularly if leverage is high and risk management systems fail. This could necessitate coordinated central bank action, including emergency liquidity injections and potential asset purchases to stabilize markets.

8. Risk Mitigation and Strategic Responses

Investors and policymakers must adopt proactive measures to mitigate the fallout from a market meltdown. Diversification across asset classes, geographies, and sectors can reduce exposure to concentrated risks. Hedging strategies, such as options, futures, and safe-haven assets like gold or government bonds, may protect portfolios against severe downside movements.

Central banks and governments play a crucial role in maintaining confidence. Transparent communication, targeted monetary and fiscal interventions, and liquidity support can prevent panic from escalating into systemic collapse. Regulatory oversight, stress testing of financial institutions, and monitoring of leverage are essential tools to manage systemic risks.

9. Looking Ahead

While predicting the exact timing of a market meltdown is impossible, the convergence of inflationary pressures, high debt levels, geopolitical uncertainty, and investor sentiment indicates elevated vulnerability in the global financial system. Awareness, preparation, and strategic risk management are critical for investors and policymakers alike.

The coming months could define the resilience of global markets. Prudent diversification, disciplined investment strategies, and vigilance in monitoring macroeconomic and geopolitical developments are essential to navigate what could be one of the most turbulent periods in recent financial history. The global economy’s interconnected nature ensures that no market is immune, and the lessons from past crashes, from 2008 to the pandemic-era turbulence, underscore the importance of readiness and measured response.

US Federal Reserve Policy and Its Impact on Global Interest RateUnderstanding the Role of the US Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve’s primary mandate is domestic: to achieve maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. To meet these objectives, the Fed uses monetary policy tools such as setting the federal funds rate, conducting open market operations, and managing its balance sheet through quantitative easing (QE) or quantitative tightening (QT). Although these tools are designed for the US economy, their effects extend well beyond national borders.

Because the US dollar is the dominant global reserve currency and a key medium for international trade, finance, and debt issuance, the Fed’s policy stance effectively acts as a benchmark for global financial conditions. When the Fed changes interest rates, global investors reassess risk, returns, and capital allocation decisions across countries.

Transmission of US Interest Rate Policy to the Global Economy

The impact of US Federal Reserve policy on global interest rates occurs through several interconnected channels.

1. Capital Flows and Investment Decisions

When the Fed raises interest rates, US assets such as Treasury bonds become more attractive due to higher yields and perceived safety. Global investors often shift capital toward the US, reducing investment flows to emerging and developing economies. This capital movement pushes up interest rates elsewhere, as countries must offer higher returns to retain or attract investors. Conversely, when the Fed cuts rates, capital tends to flow toward higher-yielding markets abroad, easing global borrowing costs.

2. Exchange Rate Effects

Higher US interest rates generally strengthen the US dollar. A stronger dollar increases the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt for countries and corporations outside the US. To defend their currencies and manage inflationary pressures, many central banks are forced to raise domestic interest rates, even if their economies are weak. Thus, Fed tightening often leads to synchronized global rate hikes.

3. Global Benchmark for Borrowing Costs

US Treasury yields serve as a global benchmark for pricing financial assets. International loans, bonds, and mortgages are frequently priced relative to US yields. When Treasury yields rise due to Fed tightening, global borrowing costs increase across both developed and emerging markets. This affects government debt servicing, corporate investment plans, and household credit conditions worldwide.

Impact on Developed Economies

In advanced economies such as the Eurozone, Japan, and the United Kingdom, central banks closely monitor Fed policy. While these economies have independent monetary authorities, they cannot ignore US policy without risking financial instability.

For example, if the Fed raises rates while another major economy keeps rates low, capital outflows may weaken that country’s currency and fuel inflation. To maintain financial balance, developed-market central banks often adjust their policies in alignment with the Fed, even if domestic conditions differ. As a result, US monetary tightening can slow economic growth globally by increasing interest rates across advanced economies.

Impact on Emerging and Developing Economies

Emerging markets are particularly sensitive to US Federal Reserve policy. Many of these countries rely heavily on foreign capital and have significant levels of dollar-denominated debt. When US rates rise, emerging markets face higher debt servicing costs, currency depreciation, and capital flight.

To stabilize their currencies and control inflation, emerging-market central banks frequently raise interest rates in response to Fed tightening. While this may help maintain financial stability, it can also suppress economic growth, increase unemployment, and strain public finances. In extreme cases, rapid Fed rate hikes have contributed to financial crises in vulnerable economies, as seen during past periods of aggressive tightening.

Inflation, Global Liquidity, and Interest Rate Cycles

The Fed’s policy stance significantly influences global liquidity conditions. During periods of low US interest rates and quantitative easing, global liquidity expands. Cheap dollar funding encourages borrowing, asset price growth, and risk-taking across the world. This environment often leads to lower global interest rates and higher asset valuations.

However, when the Fed shifts toward tightening to control inflation, global liquidity contracts. Higher rates and reduced balance sheet support tighten financial conditions worldwide, raising interest rates and reducing access to credit. This transition often exposes weaknesses in highly leveraged economies and financial systems.

Policy Coordination and Global Challenges

The global influence of US Federal Reserve policy highlights the challenges of international monetary coordination. While the Fed focuses on US economic conditions, its actions can unintentionally create economic stress elsewhere. This has led to calls for greater cooperation among major central banks, especially during periods of global crisis.

Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) often play a stabilizing role by providing financial assistance to countries affected by sharp changes in global interest rates. Swap lines between the Fed and other central banks have also become an important tool for ensuring dollar liquidity during times of market stress.

Long-Term Implications for the Global Economy

Over the long term, persistent changes in US interest rate policy can reshape global economic structures. Prolonged periods of low US rates encourage global debt accumulation, while extended tightening cycles can force painful adjustments. Countries increasingly seek to reduce dependence on dollar funding, diversify reserves, and strengthen domestic financial systems to reduce vulnerability to Fed-driven shocks.

At the same time, the Fed’s credibility and transparency play a crucial role in stabilizing expectations. Clear communication helps global markets anticipate policy moves and adjust gradually, reducing the risk of sudden interest rate spikes and financial turmoil.

Conclusion

The US Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is a powerful force shaping global interest rates and financial conditions. Through capital flows, exchange rate movements, and benchmark yield transmission, Fed decisions influence borrowing costs and economic stability across the world. While the Fed’s mandate is domestic, its global impact is unavoidable in an interconnected financial system. Understanding this relationship is essential for policymakers, investors, and economies seeking to navigate global interest rate cycles and maintain long-term financial resilience.

Global Trade Impact1. Economic Growth and Development

Global trade plays a pivotal role in stimulating economic growth. By allowing countries to specialize in the production of goods and services in which they hold a comparative advantage, trade increases overall efficiency and productivity. Nations can export products in which they are strong and import goods they lack, resulting in higher output and consumption levels. Developing countries often benefit from access to larger markets, enabling them to attract foreign investments, improve infrastructure, and create job opportunities.

Trade has also been a driving force behind industrialization. For example, countries in East Asia, such as South Korea and China, leveraged global trade to transition from agrarian economies to industrial powerhouses, significantly raising living standards. Furthermore, trade generates revenue for governments through tariffs, duties, and taxation of corporate profits, which can be reinvested in social services, infrastructure, and education.

2. Technological Advancement and Innovation

Global trade facilitates the rapid diffusion of technology and innovation across borders. When countries engage in international trade, they gain exposure to new techniques, business models, and production methods. For instance, multinational corporations often transfer technology to their foreign subsidiaries, leading to productivity improvements in host countries.

Moreover, competition in the global market incentivizes domestic firms to innovate continually. Firms are compelled to improve product quality, reduce costs, and adopt new technologies to remain competitive internationally. This not only strengthens the companies but also contributes to the broader technological and industrial advancement of their economies.

3. Employment and Labor Markets

The impact of global trade on employment is complex and multidimensional. On one hand, trade can create jobs in export-oriented industries. For instance, sectors such as electronics, automotive, and pharmaceuticals in countries like Germany, Japan, and India employ millions of workers due to strong export demand. Trade also enables service industries, including logistics, finance, and IT, to expand across borders, creating high-skilled employment opportunities.

On the other hand, increased imports and outsourcing can disrupt local industries, especially in sectors that cannot compete with cheaper foreign goods. This can lead to job losses, wage stagnation, and economic dislocation in certain regions. Governments and policymakers often respond by implementing retraining programs, social safety nets, and economic diversification strategies to mitigate negative effects on vulnerable workers.

4. Consumer Benefits

Consumers are one of the primary beneficiaries of global trade. By expanding access to a wide variety of goods and services at competitive prices, trade enhances consumer choice and purchasing power. For example, through imports, consumers in India can access technology products from the United States, electronics from South Korea, and clothing from Bangladesh at affordable prices.

Global trade also drives product quality improvements. International competition forces companies to innovate, improve service delivery, and offer better value for money. Additionally, trade often accelerates the introduction of environmentally friendly and technologically advanced products, benefiting consumers in terms of quality and sustainability.

5. Geopolitical and Strategic Implications

Global trade impacts geopolitics by fostering interdependence among nations. Countries with strong trade relations are often more likely to maintain peaceful and cooperative interactions, as their economies are intertwined. Trade agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the European Union Single Market, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), reflect how economic integration can influence diplomacy and global stability.

However, trade can also become a tool for strategic leverage. Export controls, tariffs, and sanctions are frequently used by nations to exert political pressure or protect domestic industries. Recent trade disputes between major economies, such as the United States and China, illustrate how global trade can shape international relations, sometimes generating economic uncertainty and market volatility.

6. Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

While global trade drives economic growth, it also has environmental implications. The transportation of goods across continents contributes to carbon emissions, while large-scale production can lead to resource depletion and ecological degradation. Global trade can also facilitate the spread of environmentally harmful products, such as plastics and fossil fuels, intensifying climate change challenges.

Conversely, trade can promote sustainability by enabling the global dissemination of green technologies, renewable energy solutions, and environmentally friendly production techniques. International agreements and standards, such as carbon footprint labeling and sustainable supply chain certifications, encourage businesses to adopt eco-conscious practices, demonstrating the dual nature of trade’s environmental impact.

7. Challenges and Risks

Global trade is not without its risks. Economic shocks, such as financial crises, pandemics, or geopolitical conflicts, can disrupt trade flows, leading to supply chain interruptions and price volatility. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how interconnected economies are vulnerable to global disruptions. Similarly, rising protectionism, trade wars, and regulatory barriers can hinder the free flow of goods, reduce market access, and slow economic growth.

Countries that heavily rely on exports may face economic instability if global demand declines. Developing nations, in particular, are susceptible to external shocks, emphasizing the need for diversified economies and resilient trade policies. Ensuring fair trade practices, intellectual property protection, and dispute resolution mechanisms are crucial for sustaining the long-term benefits of global trade.

8. The Role of Digital Trade and E-Commerce

In the 21st century, digital trade and e-commerce have become increasingly significant components of global trade. Platforms such as Amazon, Alibaba, and Shopify enable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to reach international customers, breaking down traditional barriers to entry. Digital services, including software, cloud computing, and financial technologies, are also increasingly traded across borders, contributing to economic growth and innovation.

Digital trade enhances efficiency, reduces transaction costs, and allows rapid adaptation to market changes. It also poses new regulatory challenges, such as data privacy, cybersecurity, and digital taxation, requiring coordinated international policies to ensure equitable growth.

Conclusion

Global trade is a powerful engine of economic development, technological progress, and cultural exchange. It generates jobs, expands consumer choice, fosters innovation, and strengthens diplomatic ties. At the same time, it presents challenges, including labor displacement, environmental concerns, economic vulnerability, and geopolitical tensions.

Maximizing the positive impact of global trade requires balanced and inclusive policies that promote sustainable development, fair competition, and resilience against global shocks. Nations must work collaboratively to ensure that trade benefits are widely shared while mitigating risks, ensuring that global trade continues to serve as a force for prosperity, innovation, and stability in the modern world.

Global Stock MarketStructure, Functioning, Trends, and Its Impact on the World Economy

The global stock market represents a vast network of interconnected financial exchanges where shares of publicly listed companies are bought and sold across countries and continents. It is one of the most important pillars of the modern financial system, serving as a bridge between companies that need capital and investors seeking opportunities for wealth creation. From the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and NASDAQ in the United States to the London Stock Exchange (LSE), Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE), and India’s NSE and BSE, the global stock market operates almost around the clock, reflecting the continuous flow of capital in a globalized economy.

At its core, the global stock market performs two fundamental functions. First, it enables companies to raise capital by issuing shares to the public. This capital is then used for expansion, research and development, infrastructure, and innovation. Second, it provides investors with a platform to participate in the growth of these companies, offering potential returns in the form of capital appreciation and dividends. Together, these functions support economic growth, job creation, and technological progress worldwide.

Structure of the Global Stock Market

The global stock market is not a single, centralized entity but a collection of national and regional markets connected through technology, capital flows, and investor sentiment. Each country typically has one or more stock exchanges regulated by domestic authorities. For example, the U.S. markets are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), while India’s markets are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). Despite differing regulations, accounting standards, and trading hours, globalization has tightly linked these markets.

Market participants include retail investors, institutional investors such as mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and increasingly, algorithmic and high-frequency traders. Advances in technology have made cross-border investing easier than ever, allowing investors in one country to invest in equities listed thousands of kilometers away with minimal friction.

Key Global Stock Market Indices

Stock market indices act as benchmarks to measure the performance of specific markets or sectors. Prominent global indices include the S&P 500, Dow Jones Industrial Average, and NASDAQ Composite in the U.S.; the FTSE 100 in the UK; the DAX in Germany; the Nikkei 225 in Japan; the Hang Seng Index in Hong Kong; and the Nifty 50 and Sensex in India. Global indices such as the MSCI World Index and MSCI Emerging Markets Index provide a broader view of international equity performance.

These indices are closely watched because they reflect investor confidence, economic expectations, and corporate health. Movements in major indices often influence investor sentiment globally, triggering rallies or sell-offs across multiple markets.

Factors Influencing the Global Stock Market

The global stock market is influenced by a wide range of factors, both economic and non-economic. Macroeconomic indicators such as GDP growth, inflation, interest rates, employment data, and trade balances play a crucial role. Central bank policies, especially interest rate decisions by institutions like the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and other major central banks, have a significant impact on global liquidity and equity valuations.

Geopolitical events also strongly affect global markets. Wars, trade disputes, sanctions, elections, and diplomatic tensions can increase uncertainty and volatility. For example, conflicts in major oil-producing regions can impact energy prices, which in turn affect stock markets worldwide. Similarly, global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how interconnected markets are, as shocks in one region quickly spread across the globe.

Corporate earnings and financial performance are another key driver. Strong earnings growth tends to support higher stock prices, while disappointing results can lead to sharp declines. Technological innovation, mergers and acquisitions, and regulatory changes also influence market dynamics.

Developed vs. Emerging Markets

The global stock market is often divided into developed markets and emerging markets. Developed markets, such as the U.S., Western Europe, Japan, and Australia, are characterized by mature economies, stable political systems, strong regulatory frameworks, and high market liquidity. These markets tend to be less volatile but may offer relatively moderate growth compared to emerging markets.

Emerging markets, including countries like India, China, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia, are associated with faster economic growth, expanding middle classes, and increasing industrialization. While these markets offer higher growth potential, they also come with higher risks due to political instability, currency fluctuations, and regulatory uncertainties. Global investors often diversify across both developed and emerging markets to balance risk and return.

Role of Technology and Globalization

Technology has transformed the global stock market dramatically. Electronic trading platforms, real-time data, mobile trading apps, and algorithmic trading have increased market efficiency and accessibility. Information now travels instantly, meaning that news released in one country can impact stock prices worldwide within seconds.

Globalization has further strengthened these connections. Multinational corporations operate across borders, and their performance depends on global supply chains, consumer demand, and international trade policies. As a result, the stock price of a company listed in one country may be influenced by economic conditions in many others.

Opportunities and Risks for Investors

The global stock market offers vast opportunities for investors. International diversification can reduce portfolio risk by spreading investments across different economies, sectors, and currencies. Investors can gain exposure to global growth trends such as digitalization, renewable energy, healthcare innovation, and artificial intelligence.

However, global investing also involves risks. Currency risk can affect returns when exchange rates fluctuate. Political and regulatory risks may impact foreign investments. Market volatility can increase during global crises, leading to sharp and sudden losses. Therefore, successful participation in the global stock market requires careful research, risk management, and a long-term perspective.

Conclusion

The global stock market is a powerful engine of economic growth and wealth creation, reflecting the collective expectations and decisions of millions of participants worldwide. It connects economies, channels savings into productive investments, and provides insights into the health of businesses and nations. While it is influenced by a complex mix of economic data, corporate performance, technology, and geopolitics, its fundamental role remains unchanged: allocating capital efficiently and enabling participation in global prosperity.

In an increasingly interconnected world, understanding the global stock market is essential not only for investors but also for policymakers, businesses, and individuals seeking to navigate the modern economy. With the right knowledge, discipline, and strategy, the global stock market can serve as a valuable tool for long-term financial growth and economic development.

Global Market Time Zone ArbitrageLeveraging the Clock for Trading Advantage

Global financial markets operate around the clock, moving seamlessly from one time zone to another as trading shifts from Asia to Europe and then to the Americas. This continuous cycle creates unique opportunities known as time zone arbitrage, where traders exploit price discrepancies, information gaps, and sentiment shifts that arise because markets in different regions open and close at different times. Global market time zone arbitrage is not about illegal exploitation; rather, it is a strategic approach that takes advantage of how information, liquidity, and trader behavior flow across time zones.

Understanding Time Zone Arbitrage

Time zone arbitrage refers to the practice of using the staggered opening and closing hours of global markets to anticipate price movements or capture temporary inefficiencies. For example, developments in the US market after Indian market hours can significantly impact Asian markets the next day. Similarly, movements in Asian markets during their trading session often influence European markets when they open. Traders who monitor and interpret these transitions can position themselves ahead of the crowd.

Unlike classical arbitrage, which focuses on simultaneous price differences of the same asset in different markets, time zone arbitrage is more anticipatory and strategic. It relies on understanding how price discovery unfolds over time rather than at a single moment.

Global Market Structure and Time Zones

The global trading day typically follows this sequence:

Asian Session (Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, India)

European Session (London, Frankfurt, Paris)

US Session (New York, Chicago)

Each session has distinct characteristics. Asian markets are often influenced by regional economic data and overnight US market cues. European markets tend to react to both Asian performance and early macroeconomic announcements. US markets, being the most liquid, often set the global tone, especially after major economic data releases or Federal Reserve announcements.

This handoff from one region to another is where time zone arbitrage opportunities arise.

Information Flow and Overnight Gaps

One of the most important drivers of time zone arbitrage is information asymmetry. Economic data, corporate earnings, geopolitical news, and central bank statements often occur when certain markets are closed. When those markets reopen, prices may gap up or down to reflect the new information.

Traders who analyze overnight developments can anticipate these gaps. For instance, if US indices rally strongly due to positive economic data, Asian equity markets often open higher. A trader positioned in index futures or ETFs before the Asian open can benefit from this expected move.

Similarly, negative global news released during Asian hours can affect European and US markets later in the day, creating opportunities for short positions or hedging strategies.

Cross-Market Influence and Lead–Lag Relationships

Time zone arbitrage also relies heavily on lead–lag relationships between markets. Certain markets tend to lead others due to their size, liquidity, or economic influence. The US equity market often leads global equities, while US bond yields and the dollar influence currencies and emerging markets worldwide.

For example:

A sharp rise in US bond yields during the US session may pressure emerging market equities and currencies in the following Asian session.

Strong performance in Asian technology stocks can influence European tech indices at the open.

Movements in crude oil during US trading hours can affect energy stocks in Asian and European markets the next day.

Understanding these relationships allows traders to forecast probable reactions rather than reacting after the move has already occurred.

Instruments Used in Time Zone Arbitrage

Time zone arbitrage is applied across multiple asset classes:

Equity Index Futures: Such as S&P 500, Nikkei, DAX, and Nifty futures, which trade nearly 24 hours.

Currencies (Forex): The forex market operates 24/5, making it ideal for time zone-based strategies.

Commodities: Crude oil, gold, and base metals often react to global news across sessions.

ETFs and ADRs: Used to gain exposure to foreign markets during domestic trading hours.

These instruments allow traders to act even when the underlying cash market is closed.

Role of Volatility and Liquidity

Volatility and liquidity vary by session, which is crucial for time zone arbitrage. Asian sessions may show lower volatility compared to US sessions, while European sessions often experience sharp moves during overlapping hours with the US.

Professional traders adjust position size and execution strategies based on session liquidity. Lower liquidity can exaggerate price movements, creating both opportunity and risk. Time zone arbitrage traders must balance the potential for outsized gains against slippage and execution costs.

Risk Management in Time Zone Arbitrage

While time zone arbitrage offers opportunities, it also carries risks:

Unexpected News: Sudden geopolitical events or policy announcements can invalidate expectations.

False Correlations: Lead–lag relationships can break down during unusual market conditions.

Gap Risk: Overnight gaps can move sharply against positions with limited exit options.

Effective risk management includes predefined stop-loss levels, diversification across markets, and awareness of economic calendars across regions.

Technology and Data in Modern Arbitrage

Advances in technology have enhanced time zone arbitrage strategies. Real-time global news feeds, economic calendars, algorithmic trading systems, and quantitative models help traders analyze cross-market relationships faster and more accurately. Institutional players often use automated systems to exploit these opportunities, but informed retail traders can still benefit through disciplined analysis and timing.

Relevance for Emerging Market Traders

For traders in emerging markets like India, time zone arbitrage is especially relevant. Global cues from US and European markets strongly influence domestic indices, currencies, and commodities. Monitoring global market closures, futures movement, and overnight news can significantly improve decision-making at the local market open.

Conclusion

Global market time zone arbitrage is a powerful trading approach that transforms the world’s trading clock into a strategic asset. By understanding how markets interact across time zones, how information travels, and how different sessions influence one another, traders can anticipate movements rather than chase them. While not risk-free, time zone arbitrage rewards preparation, global awareness, and disciplined execution. In an interconnected financial world, mastering time-based market dynamics is no longer optional—it is a key component of modern global trading success.

The Bond Market: Backbone of the Global Financial SystemWhat Is the Bond Market?

The bond market is a marketplace where debt securities, known as bonds, are issued and traded. When an entity issues a bond, it is essentially borrowing money from investors. In return, the issuer promises to pay periodic interest (called coupon payments) and repay the principal amount (face value) at a specified maturity date. Bonds are issued by governments, municipalities, corporations, and supranational institutions such as the World Bank.

The bond market is divided into two main segments: the primary market, where new bonds are issued, and the secondary market, where existing bonds are traded among investors. The smooth functioning of both segments ensures efficient capital allocation and liquidity.

Types of Bonds

The bond market encompasses a wide variety of instruments, each serving different purposes:

Government Bonds

These are issued by national governments to finance fiscal deficits, infrastructure projects, and public spending. Examples include U.S. Treasury bonds, Indian Government Securities (G-Secs), and UK Gilts. They are generally considered low-risk because they are backed by sovereign authority.

Municipal Bonds

Issued by states, cities, or local authorities, municipal bonds finance public projects such as roads, schools, and hospitals. In many countries, interest income from these bonds may carry tax advantages.

Corporate Bonds

Companies issue corporate bonds to fund expansion, acquisitions, or refinancing of debt. These bonds typically offer higher yields than government bonds to compensate for higher credit risk.

High-Yield (Junk) Bonds

Issued by entities with lower credit ratings, these bonds offer higher interest rates but come with increased default risk.

Inflation-Linked Bonds

These bonds protect investors against inflation by adjusting interest payments or principal values in line with inflation indices.

Zero-Coupon Bonds

These bonds do not pay periodic interest but are issued at a discount and redeemed at face value upon maturity.

Role of the Bond Market in the Economy

The bond market serves several crucial economic functions:

Capital Formation: It provides long-term funding for governments and businesses without diluting ownership, unlike equity financing.

Benchmark for Interest Rates: Government bond yields often act as reference rates for loans, mortgages, and other financial instruments.

Monetary Policy Transmission: Central banks use bond markets to implement monetary policy through open market operations, quantitative easing, or bond yield targeting.

Risk Management: Bonds help investors diversify portfolios and manage risk, especially during periods of equity market volatility.

Bond Pricing and Yields

Bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship. When bond prices rise, yields fall, and when prices fall, yields rise. Several factors influence bond prices:

Interest Rates: Rising interest rates generally lead to falling bond prices, as newer bonds offer higher yields.

Credit Risk: Bonds issued by entities with weaker credit profiles trade at lower prices and higher yields.

Inflation Expectations: Higher expected inflation erodes the real return on bonds, reducing their attractiveness.

Time to Maturity: Longer-maturity bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes.

Yield curves, which plot bond yields across different maturities, provide valuable insight into economic expectations. An upward-sloping curve suggests economic growth, while an inverted yield curve is often seen as a warning signal of recession.

Bond Market Participants

The bond market attracts a wide range of participants:

Institutional Investors: Pension funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds are major players due to their need for stable income.

Central Banks: They influence liquidity and interest rates through bond purchases and sales.

Commercial Banks: Banks invest in bonds for liquidity management and regulatory requirements.

Retail Investors: Individual investors participate through direct bond purchases or bond mutual funds and ETFs.

Hedge Funds and Traders: These participants seek to profit from interest rate movements, arbitrage opportunities, and credit spreads.

Global Bond Markets

Globally, the bond market is significantly larger than the equity market. The United States has the largest and most liquid bond market, followed by Europe and Japan. Emerging markets, including India and China, have rapidly growing bond markets as they develop domestic debt financing and reduce reliance on foreign currency borrowing.

International bond markets facilitate cross-border capital flows but also expose economies to global interest rate cycles and currency risks. Events such as U.S. Federal Reserve policy changes often have widespread impacts on global bond yields and capital movements.

Risks in the Bond Market

While bonds are often considered safer than equities, they are not risk-free. Key risks include:

Interest Rate Risk: The risk of bond prices falling due to rising interest rates.

Credit Risk: The possibility that the issuer may default on interest or principal payments.

Inflation Risk: Inflation can erode the real value of bond returns.

Liquidity Risk: Some bonds may be difficult to sell quickly without price concessions.

Reinvestment Risk: The risk that future coupon payments may be reinvested at lower interest rates.

Bond Market and Financial Stability

The bond market is closely linked to financial stability. Sharp movements in bond yields can affect banking systems, government finances, and currency markets. Sovereign bond crises, such as those seen in parts of Europe during the debt crisis, highlight how bond market stress can spill over into broader economic turmoil.

At the same time, a well-functioning bond market enhances resilience by providing alternative funding sources, distributing risk, and improving transparency in pricing credit and interest rate expectations.

Conclusion

The bond market is the backbone of the global financial system, underpinning government financing, corporate investment, and monetary policy implementation. Its size, depth, and influence extend far beyond simple debt instruments, shaping interest rates, economic cycles, and financial stability. For investors, bonds offer income, diversification, and risk management benefits. For economies, they enable sustainable growth and efficient capital allocation. As global financial markets evolve, the bond market will continue to play a critical role in balancing risk, return, and stability in an increasingly interconnected world.

The Best Way of Trading in the Cryptocurrency Market1. Understand the Nature of the Crypto Market

Before trading, it is essential to understand how crypto markets differ from traditional markets. Cryptocurrencies are decentralized, largely unregulated in many regions, and driven by innovation, narratives, and global participation. Prices can move sharply within minutes due to news, whale activity, macroeconomic events, or social media sentiment. Volatility is both the biggest opportunity and the biggest risk. Successful traders accept volatility as a feature, not a flaw, and design strategies that can survive sudden price swings.

2. Choose the Right Trading Style

The best way to trade crypto depends heavily on your personality, time availability, and risk tolerance. Common trading styles include scalping, day trading, swing trading, and position trading.

Scalping focuses on very small price movements and requires speed, discipline, and low transaction costs.

Day trading involves entering and exiting positions within the same day to avoid overnight risk.

Swing trading aims to capture medium-term trends lasting days or weeks.

Position trading focuses on long-term trends based on fundamentals and macro cycles.

There is no universally best style; the best approach is the one you can execute consistently without emotional stress.

3. Focus on Liquidity and Quality Assets

A key rule in crypto trading is to trade liquid and well-established assets, especially for beginners. Coins like Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH) have high liquidity, tighter spreads, and more reliable technical structures. Low-liquidity altcoins can offer explosive gains, but they also carry higher risks of manipulation, slippage, and sudden crashes. The best way to trade is to prioritize quality over hype and avoid chasing every new token or trend.

4. Use Technical Analysis as a Core Tool

Technical analysis plays a central role in crypto trading because price action reflects collective market psychology. Learning how to read charts, identify trends, support and resistance levels, chart patterns, and indicators like moving averages, RSI, and volume is essential. However, indicators should not be used blindly. The best traders focus on price structure and market context first, using indicators only as confirmation tools rather than decision-makers.

5. Combine Fundamentals and Narratives

While technical analysis helps with entries and exits, fundamentals and narratives help with direction and conviction. Understanding a project’s use case, tokenomics, developer activity, ecosystem growth, and adoption trends can help traders decide which assets are worth trading. In crypto, narratives such as Layer-2 scaling, AI tokens, DeFi, NFTs, or Bitcoin halving cycles often drive sustained trends. The best way to trade is to align technical setups with strong narratives rather than trading random coins.

6. Master Risk Management

Risk management is the most important factor in long-term success. Even the best strategy will fail without proper risk control. Traders should never risk more than a small percentage of their capital on a single trade, typically 1–2%. Stop-loss orders are essential to protect against sudden market moves. Position sizing, risk-to-reward ratios, and capital preservation must always come before profit maximization. The best way of trading is to survive long enough to let skill compound.

7. Control Emotions and Trading Psychology

The crypto market is emotionally intense. Fear of missing out (FOMO), panic selling, overconfidence, and revenge trading are common reasons for losses. Successful traders develop emotional discipline by following predefined rules and avoiding impulsive decisions. Keeping a trading journal, reviewing mistakes, and maintaining realistic expectations helps build psychological resilience. The best way to trade crypto is to remain calm and rational, even during extreme volatility.

8. Avoid Overtrading and Leverage Abuse

Because crypto markets are always open, many traders fall into the trap of overtrading. Constant trading increases transaction costs and emotional fatigue. Similarly, excessive leverage can wipe out accounts quickly during sudden price swings. While leverage can be a useful tool for experienced traders, the best way of trading is to use it conservatively or avoid it entirely until consistent profitability is achieved.

9. Stay Updated but Filter Information

Crypto markets react quickly to news, but not all information is valuable. Social media is full of hype, rumors, and misleading advice. The best traders learn to filter noise and focus on credible sources, on-chain data, macro trends, and official announcements. Being informed is important, but reacting emotionally to every headline is dangerous.

10. Build Consistency and a Long-Term Mindset

The best way of trading in the crypto market is to think in terms of consistency rather than quick riches. Profitable trading is the result of repeated correct decisions over time, not one lucky trade. Losses are part of the process, and even top traders experience drawdowns. What separates successful traders is their ability to learn, adapt, and remain disciplined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the best way of trading in the cryptocurrency market is a balanced and professional approach that combines market understanding, a suitable trading style, technical and fundamental analysis, strict risk management, and strong psychological control. Crypto trading is not gambling; it is a skill that improves with education, experience, and discipline. Those who focus on process over profits, protect their capital, and continuously refine their strategies are the ones who succeed in the long run.

Competitive Devaluation: The New Currency War Introduction

Competitive devaluation has re-emerged as a powerful and controversial tool in the modern global economy. In a world marked by slowing growth, geopolitical fragmentation, rising debt, and persistent trade imbalances, countries increasingly look toward their exchange rates as a lever to protect domestic interests. Competitive devaluation refers to a situation where countries deliberately weaken their currencies to gain an advantage in international trade, stimulate exports, attract foreign investment, and support domestic growth. While it may provide short-term relief, it often triggers retaliation, financial instability, and long-term structural risks. In today’s interconnected financial system, competitive devaluation is no longer an isolated policy choice—it is part of a broader, ongoing currency war.

Understanding Competitive Devaluation

At its core, competitive devaluation is about making a nation’s goods and services cheaper on the global market by reducing the value of its currency. When a currency depreciates, exports become more attractive to foreign buyers, while imports become more expensive for domestic consumers. Governments and central banks can influence devaluation through interest rate cuts, quantitative easing, foreign exchange interventions, capital controls, or fiscal expansion.

Unlike market-driven depreciation caused by economic fundamentals, competitive devaluation is intentional and strategic. It is often pursued during periods of weak global demand, when countries struggle to grow through productivity or innovation alone.

Why Competitive Devaluation Is Prominent Now

The current global environment has made competitive devaluation more appealing and more frequent:

Slowing Global Growth

As major economies face stagnation or low growth, traditional policy tools lose effectiveness. Currency depreciation becomes a shortcut to stimulate demand.

High Debt Levels

Inflation and currency weakness reduce the real value of debt, making devaluation attractive for highly indebted governments.

Fragmented Global Trade

De-globalization, sanctions, and supply chain realignment have increased trade competition, pushing nations to protect export competitiveness.

Diverging Monetary Policies

Differences in interest rate paths between countries create sharp currency movements, often interpreted as deliberate devaluation even when policy goals differ.

Geopolitical Tensions

Economic warfare increasingly complements military and diplomatic strategies, with currencies becoming tools of influence.

Mechanisms of Competitive Devaluation

Countries employ several mechanisms to weaken their currencies:

Interest Rate Reductions: Lower rates reduce capital inflows and weaken currency demand.

Quantitative Easing: Injecting liquidity increases money supply, putting downward pressure on the currency.

Direct FX Intervention: Central banks sell their own currency in foreign exchange markets.

Capital Controls: Restricting inflows or encouraging outflows limits currency appreciation.

Fiscal Expansion: Large deficits can undermine investor confidence and weaken exchange rates.

Often, these tools are framed as domestic stabilization policies, even when their external impact is clear.

Short-Term Benefits of Competitive Devaluation

Competitive devaluation can deliver immediate advantages:

Boost to Exports: Domestic producers gain price competitiveness abroad.

Improved Trade Balance: Reduced imports and increased exports can narrow deficits.

Economic Stimulus: Export-led growth supports employment and industrial output.

Asset Market Support: Weaker currency often lifts equity markets through higher earnings translations.

Debt Relief: Inflationary effects reduce real debt burdens.

These benefits explain why competitive devaluation remains politically attractive, especially during economic downturns.

The Hidden Costs and Risks

Despite its appeal, competitive devaluation carries significant risks:

Retaliation and Currency Wars

When one country devalues, others respond, neutralizing the original advantage and escalating tensions.

Imported Inflation

Higher import prices raise inflation, eroding purchasing power and hurting consumers.

Capital Flight

Persistent devaluation undermines investor confidence, leading to outflows and financial instability.

Erosion of Monetary Credibility

Markets may lose faith in central bank independence and long-term policy discipline.

Misallocation of Resources

Artificial competitiveness discourages productivity improvements and structural reforms.

In the long run, no country gains if all currencies weaken simultaneously.

Competitive Devaluation in Emerging vs. Developed Economies

The impact differs across economies:

Emerging Markets face higher risks of capital outflows, debt stress (especially if debt is dollar-denominated), and inflation shocks.

Developed Economies often have more policy credibility and reserve currency status, allowing prolonged monetary easing without immediate crises.

However, even advanced economies are not immune, as persistent currency weakness can distort global capital flows and asset valuations.

Role of the US Dollar and Global Imbalances

The dominance of the US dollar complicates competitive devaluation. Many countries manage their currencies relative to the dollar, making US monetary policy a global anchor. When the dollar strengthens, others face pressure to devalue to maintain competitiveness. Conversely, when the dollar weakens, it can export inflation worldwide.

This asymmetry fuels global imbalances and reinforces the cycle of competitive devaluation, especially among export-driven economies.

Competitive Devaluation vs. Structural Competitiveness

A key criticism of competitive devaluation is that it substitutes currency manipulation for genuine economic reform. Sustainable competitiveness comes from productivity gains, innovation, infrastructure investment, education, and institutional strength—not from weaker currencies alone.

Countries relying too heavily on devaluation risk falling into a trap of low productivity, high inflation, and volatile capital flows.

Future Outlook: Is Competitive Devaluation Sustainable?

Competitive devaluation is likely to persist in the near term as global uncertainty remains high. However, its effectiveness will diminish as more countries adopt similar strategies. Over time, coordinated frameworks, regional trade arrangements, and currency diversification may limit its scope.

The future global system may shift toward:

Greater use of bilateral trade settlements

Reduced reliance on single reserve currencies

Increased scrutiny of currency practices by international institutions

Yet without genuine global coordination, competitive devaluation will remain a recurring feature of economic crises.

Conclusion

Competitive devaluation is once again at the center of global economic strategy, reflecting deep structural stresses in the world economy. While it offers short-term relief and political appeal, it carries long-term costs that can undermine stability, trust, and growth. In the end, currency weakness cannot replace real economic strength. Nations that balance exchange rate flexibility with structural reform, policy credibility, and international cooperation will be best positioned to navigate the evolving currency landscape.

What a Stronger US Dollar Means for Global MarketsThe US Dollar Index (DXY), which measures the strength of the US dollar against a basket of major currencies (EUR, JPY, GBP, CAD, SEK, and CHF), has surged today, drawing the attention of global financial markets. A rising DXY is never an isolated event—it reflects deeper macroeconomic forces and triggers ripple effects across equities, commodities, bonds, emerging markets, and global trade. Understanding why the DXY is rising and what it implies is essential for traders, investors, policymakers, and businesses alike.

Understanding the DXY Surge

A DXY surge indicates broad-based strength in the US dollar relative to its peers. This typically occurs when global capital flows toward the United States in search of safety, higher returns, or monetary stability. The dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency amplifies these moves, especially during periods of uncertainty or policy divergence between the US and other major economies.

Today’s surge suggests a renewed preference for dollar-denominated assets, reflecting changing expectations around growth, inflation, interest rates, or global risk sentiment.

Key Drivers Behind the DXY Surge

One of the most important drivers of a rising DXY is interest rate expectations. When markets anticipate that the US Federal Reserve will maintain higher interest rates for longer—or delay rate cuts—the dollar tends to strengthen. Higher yields on US Treasury bonds attract foreign capital, increasing demand for dollars.

Another major factor is risk aversion. During times of geopolitical tension, financial stress, or economic uncertainty, investors often move money into safe-haven assets. The US dollar, along with US Treasuries, is considered the safest and most liquid store of value in the global system. Even mild increases in uncertainty can trigger sharp dollar rallies.

Relative economic strength also plays a crucial role. If US economic data—such as employment, GDP growth, or consumer spending—outperforms that of Europe, Japan, or the UK, capital naturally flows toward the US. This divergence boosts the DXY as other currencies weaken in comparison.

Additionally, weakness in major counterpart currencies, particularly the euro and yen, can mechanically push the DXY higher. Structural challenges, slower growth, or accommodative monetary policies in other economies often translate into currency depreciation against the dollar.

Impact on Global Equity Markets

A surging DXY often creates headwinds for global equities, especially outside the United States. For emerging markets, a stronger dollar raises the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt, pressures local currencies, and can lead to capital outflows. As a result, equity markets in developing economies tend to underperform during strong dollar phases.

Even US equities are not immune. While domestic-focused companies may remain resilient, multinational corporations can face earnings pressure because overseas revenues translate into fewer dollars. Sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods with significant global exposure may experience valuation compression.

However, defensive sectors and companies with strong pricing power often fare better, as they are less sensitive to currency fluctuations.

Effect on Commodities

Commodities are typically priced in US dollars, making them inversely correlated with the DXY. When the dollar strengthens, commodities like gold, silver, crude oil, and industrial metals become more expensive for non-US buyers, reducing demand.

Gold is particularly sensitive to dollar movements. A DXY surge often puts downward pressure on gold prices, especially when accompanied by rising real yields. However, in extreme risk-off environments, gold can sometimes hold firm due to its safe-haven appeal, even as the dollar rises.

For oil and base metals, a strong dollar usually signals tighter financial conditions, which can dampen global growth expectations and suppress prices.

Implications for Bond Markets

The bond market is both a cause and a consequence of a rising DXY. Higher US yields attract foreign capital, strengthening the dollar. At the same time, strong dollar inflows can reinforce demand for Treasuries, particularly during periods of uncertainty.

For emerging market bonds, the impact is often negative. A stronger dollar tightens global liquidity, increases refinancing risks, and raises borrowing costs. This can widen credit spreads and increase volatility in global fixed-income markets.

Currency Wars and Global Policy Response

A sustained DXY surge can place pressure on other central banks. Countries facing currency depreciation may be forced to choose between supporting growth and defending their currencies. Some may raise interest rates to stem capital outflows, while others may tolerate weaker currencies to support exports.

This dynamic sometimes fuels concerns about competitive devaluations or “currency wars,” where nations attempt to gain trade advantages through weaker exchange rates. While rarely explicit, such tensions can influence trade negotiations and global economic cooperation.

Impact on India and Emerging Economies

For economies like India, a rising DXY often leads to currency depreciation, imported inflation, and higher costs for commodities such as crude oil. This can complicate monetary policy decisions, as central banks must balance inflation control with growth support.

Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) may also reduce exposure to emerging markets during periods of dollar strength, leading to short-term volatility in equity and bond markets. However, countries with strong foreign exchange reserves and improving fundamentals tend to weather these phases better.

What the DXY Surge Signals Going Forward

A DXY surge today may be signaling tighter global financial conditions, persistent inflation concerns, or prolonged monetary policy divergence. Historically, extended periods of dollar strength often coincide with slower global growth and higher market volatility.

However, dollar cycles are not permanent. Once interest rate expectations stabilize or global growth broadens beyond the US, the DXY can peak and reverse. For long-term investors, understanding where the dollar sits in its broader cycle is more important than reacting to daily moves.

Conclusion

The surge in the DXY today is more than just a currency move—it is a reflection of global capital flows, policy expectations, and risk sentiment. A stronger dollar reshapes asset allocation decisions, pressures commodities, challenges emerging markets, and influences central bank strategies worldwide.

For traders, the DXY acts as a powerful macro indicator, offering clues about liquidity, risk appetite, and future market direction. For investors and policymakers, it serves as a reminder of how interconnected the global financial system remains, with the US dollar still firmly at its core.

The Interplay of Investors, Traders, and Policymakers1. The Global Trading Ecosystem: An Overview

Global trading encompasses equity markets, bond markets, commodities, currencies (forex), derivatives, and alternative assets such as cryptocurrencies. These markets operate across multiple time zones, making trading a 24-hour phenomenon. Capital flows seamlessly from one region to another in search of returns, safety, or diversification. This fluid movement is driven by information—economic data, corporate earnings, geopolitical events, and policy decisions—which is instantly reflected in asset prices.

Within this ecosystem, investors provide long-term capital, traders ensure liquidity and efficient pricing, and policymakers establish the rules of the game. The balance among these participants determines market confidence, volatility, and sustainability.

2. Investors: Long-Term Capital and Value Creation

Investors are the cornerstone of global trading. They typically operate with a medium- to long-term horizon, aiming to grow wealth through appreciation, income, or both. Institutional investors such as pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and endowments dominate global capital flows. Retail investors, though smaller individually, collectively have a significant impact, especially with the rise of online platforms.

Investors focus on fundamentals—economic growth, corporate profitability, balance sheets, governance, and long-term trends such as demographics, technology, and climate transition. Their decisions determine where capital is allocated globally: emerging markets versus developed economies, equities versus bonds, or traditional industries versus new-age sectors.

In global trading, investors also play a stabilizing role. By holding assets through market cycles, they help dampen excessive volatility. Long-term investments in infrastructure, manufacturing, and innovation contribute to economic development and employment. However, shifts in investor sentiment—such as risk-on or risk-off behavior—can trigger massive cross-border capital movements, impacting currencies, interest rates, and asset prices worldwide.

3. Traders: Liquidity, Price Discovery, and Market Efficiency

Traders operate on shorter time horizons compared to investors. They range from intraday and swing traders to high-frequency trading (HFT) firms and proprietary desks at global banks. Traders focus on price action, liquidity, volatility, and market psychology rather than long-term fundamentals.

Their primary contribution to global trading is liquidity. By continuously buying and selling, traders ensure that markets remain active and that investors can enter or exit positions efficiently. This liquidity is crucial for accurate price discovery, allowing asset prices to reflect real-time information.

In modern global markets, technology plays a dominant role. Algorithmic and quantitative trading strategies analyze massive datasets in milliseconds, exploiting small price inefficiencies across geographies and asset classes. While this enhances efficiency, it can also amplify short-term volatility, especially during periods of stress.

Traders are highly sensitive to macroeconomic data releases, central bank announcements, geopolitical developments, and unexpected news. Their rapid reactions often cause sharp intraday movements, which can later be assessed and absorbed by longer-term investors.

4. Policymakers: Regulation, Stability, and Economic Direction

Policymakers—governments, central banks, and regulatory authorities—set the framework within which global trading operates. Their decisions influence interest rates, inflation, currency values, capital flows, and investor confidence.

Central banks play a particularly critical role. Through monetary policy tools such as interest rates, open market operations, and liquidity measures, they directly affect asset prices and risk appetite. For example, accommodative monetary policy tends to support equities and risk assets, while tightening cycles often strengthen currencies and pressure valuations.

Fiscal policymakers influence markets through taxation, public spending, subsidies, and trade policies. Infrastructure spending can boost equities and commodities, while protectionist measures may disrupt global supply chains and increase market uncertainty.

Regulatory bodies ensure market integrity by enforcing transparency, preventing fraud, managing systemic risk, and protecting investors. Well-designed regulation fosters confidence and long-term participation, while excessive or unpredictable regulation can deter capital and reduce market efficiency.

5. Interaction Between Investors, Traders, and Policymakers

The global trading environment is shaped by the continuous interaction among these three groups. Policymaker actions influence investor expectations and trader behavior. Traders interpret policy signals instantly, often driving short-term price movements. Investors then reassess long-term implications and adjust portfolios accordingly.

For example, a central bank’s indication of future rate cuts may trigger an immediate rally led by traders, followed by sustained inflows from investors reallocating capital toward growth assets. Conversely, unexpected policy tightening can cause sharp sell-offs, currency appreciation, and capital outflows from riskier markets.

This interaction is not one-way. Market reactions also influence policymakers. Severe volatility, financial instability, or market crashes may prompt intervention through liquidity support, regulatory changes, or fiscal stimulus. Thus, global trading is a dynamic feedback loop rather than a static system.

6. Globalization, Geopolitics, and Cross-Border Complexity

Global trading does not occur in isolation from political and geopolitical realities. Trade wars, sanctions, military conflicts, and diplomatic shifts can significantly alter capital flows and market structures. Investors reassess country risk, traders exploit volatility, and policymakers respond with strategic measures.

Emerging markets are particularly sensitive to global capital flows driven by developed-market monetary policy. Changes in interest rates in major economies can influence currencies, bond yields, and equity markets worldwide, highlighting the asymmetry of global financial power.

7. Technology and the Future of Global Trading

Advancements in technology continue to reshape global trading. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, blockchain, and digital assets are transforming how markets operate. Retail participation has expanded due to easy access to information and low-cost trading platforms, blurring the line between investors and traders.

Policymakers face new challenges in regulating digital markets, managing systemic risks, and ensuring fair access while fostering innovation. The balance between efficiency, stability, and inclusivity will define the next phase of global trading.

8. Conclusion

Global trading is a complex, interconnected system driven by the collective actions of investors, traders, and policymakers. Investors provide long-term capital and stability, traders ensure liquidity and efficient pricing, and policymakers set the economic and regulatory framework. Their interaction determines market direction, volatility, and resilience.

In an increasingly globalized and technologically advanced world, understanding this interplay is crucial for navigating financial markets effectively. As economic power shifts, new asset classes emerge, and policy challenges grow, the role of global trading will remain central to shaping economic outcomes and wealth creation across the world.

Managing Currency Pegs1. Introduction to Currency Pegs

A currency peg is an exchange rate policy in which a country fixes the value of its domestic currency to another major currency (such as the US dollar or euro), a basket of currencies, or a commodity like gold. The primary objective of a currency peg is to maintain exchange rate stability, reduce volatility in international trade, and enhance investor confidence. Many developing and emerging economies adopt currency pegs to anchor inflation expectations and stabilize their macroeconomic environment.

However, managing a currency peg is complex and requires strong institutional capacity, sufficient foreign exchange reserves, and disciplined economic policies. Failure to manage a peg effectively can lead to severe financial crises, as seen in historical episodes such as the Asian Financial Crisis (1997) and Argentina’s currency collapse (2001).

2. Types of Currency Peg Systems

a) Fixed Peg

Under a fixed peg, the currency is tied at a constant rate to another currency. The central bank intervenes actively to maintain this rate.

b) Crawling Peg

A crawling peg allows gradual, pre-announced adjustments to the exchange rate, usually to offset inflation differentials.

c) Peg to a Basket of Currencies

Instead of a single currency, some countries peg to a basket, reducing dependence on one economy and smoothing external shocks.

d) Currency Board Arrangement

A currency board is a strict form of peg where domestic currency issuance is fully backed by foreign reserves, leaving little room for monetary discretion.

3. Objectives of Managing Currency Pegs

The management of currency pegs is driven by several economic objectives:

Exchange rate stability to promote trade and investment

Inflation control, especially in high-inflation economies

Policy credibility by anchoring monetary expectations

Reduction of currency risk for exporters and importers

Macroeconomic discipline, forcing governments to limit excessive deficits