Sentiment Analysis Using AI and Big DataConcept of Sentiment Analysis

At its core, sentiment analysis aims to classify data into emotional categories such as positive, negative, or neutral. More advanced systems go beyond simple polarity and detect emotions like happiness, anger, fear, trust, or anticipation. AI-driven sentiment analysis does not just identify what people are talking about but also how they feel about it. This makes it a crucial tool for businesses, governments, financial markets, and researchers.

Role of AI in Sentiment Analysis

AI is the backbone of modern sentiment analysis. Traditional rule-based systems relied on predefined dictionaries of positive and negative words, which were limited and often inaccurate. AI, particularly Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL), has transformed this field by enabling models to learn patterns directly from data.

Natural Language Processing (NLP), a branch of AI, allows machines to understand human language. Techniques such as tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition, and semantic analysis help models interpret context, sarcasm, slang, and linguistic variations. Advanced models like transformers and large language models can understand sentiment even when it is implicit or context-dependent.

AI also supports multilingual sentiment analysis, enabling global organizations to analyze sentiments across different languages and cultures without manual translation.

Big Data as the Foundation

Big Data refers to datasets characterized by high volume, velocity, and variety. Sentiment analysis depends heavily on Big Data because emotions and opinions are scattered across millions of data points. Social media platforms, e-commerce websites, financial news feeds, and IoT-generated data continuously stream information that must be captured, stored, and processed in real time.

Big Data technologies such as distributed databases, cloud storage, and parallel processing frameworks allow sentiment analysis systems to scale efficiently. They make it possible to analyze historical data for long-term trends as well as real-time data for immediate insights.

Integration of AI and Big Data

The real power of sentiment analysis emerges when AI and Big Data work together. Big Data provides the raw material—massive, diverse datasets—while AI provides the intelligence to interpret them. AI models are trained on large datasets to improve accuracy, adapt to changing language patterns, and reduce bias.

For example, in real-time sentiment analysis, streaming data pipelines ingest live tweets or news updates, while AI models instantly analyze sentiment and generate insights. This integration is especially valuable in fast-moving domains like financial markets or crisis management.

Applications of Sentiment Analysis

Business and Marketing

Companies use sentiment analysis to understand customer opinions about products, services, and brands. By analyzing reviews, social media comments, and feedback surveys, businesses can identify strengths, weaknesses, and emerging issues. This helps in product development, brand reputation management, and personalized marketing strategies.

Financial Markets

In trading and investment, sentiment analysis plays a critical role. AI systems analyze news articles, earnings reports, social media chatter, and analyst opinions to gauge market sentiment. Positive or negative sentiment often influences stock prices, volatility, and trading volumes. Hedge funds and algorithmic traders increasingly rely on sentiment-driven signals to gain an edge.

Politics and Public Policy

Governments and political organizations use sentiment analysis to understand public opinion on policies, elections, and social issues. By analyzing speeches, media coverage, and social platforms, policymakers can assess public response and adjust communication strategies accordingly.

Customer Support and Service

Sentiment analysis helps organizations monitor customer emotions during interactions such as emails, chats, and call transcripts. AI systems can flag highly negative sentiments in real time, allowing human agents to intervene and improve customer satisfaction.

Healthcare and Social Research

In healthcare, sentiment analysis is used to study patient feedback, mental health indicators, and public responses to health campaigns. Researchers analyze online discussions to understand stress levels, emotional well-being, and societal trends.

Advanced Sentiment Analysis Techniques

Modern sentiment analysis goes beyond basic classification. Aspect-based sentiment analysis identifies sentiment toward specific features, such as battery life or customer service. Emotion detection recognizes nuanced feelings rather than simple polarity. Multimodal sentiment analysis combines text, audio, and visual data to provide deeper emotional insights, such as analyzing facial expressions alongside spoken words.

AI models continuously improve through reinforcement learning and feedback loops, adapting to new slang, cultural shifts, and evolving language usage.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its advancements, sentiment analysis faces several challenges. Sarcasm, irony, and ambiguous language can mislead AI models. Cultural and regional differences affect how emotions are expressed, making global sentiment analysis complex. Data quality and bias are also major concerns, as models trained on biased datasets can produce skewed results.

Privacy and ethical considerations are increasingly important. Organizations must ensure responsible data usage, transparency, and compliance with data protection regulations when analyzing user-generated content.

Future of Sentiment Analysis

The future of sentiment analysis lies in deeper contextual understanding and real-time intelligence. As AI models become more sophisticated and Big Data infrastructure more powerful, sentiment analysis will move from descriptive insights to predictive and prescriptive intelligence. Systems will not only detect sentiment but also forecast emotional trends and recommend actions.

Integration with generative AI, voice analysis, and emotional AI will further expand its scope, enabling machines to understand human emotions more naturally and accurately.

Conclusion

Sentiment analysis using AI and Big Data has become an essential tool in the modern data-driven world. By combining massive datasets with intelligent algorithms, organizations can decode human emotions at scale and transform raw opinions into actionable insights. While challenges remain, continuous advancements in AI, Big Data, and ethical frameworks are shaping sentiment analysis into a more accurate, responsible, and impactful technology for the future.

Wave Analysis

Lower Lows For ONDOONDO Potentially printing sub-wave 5 of an extended 3rd wave of one higher degree. This suggests lower lows for ONDO. This also hints that the 5th impulsive wave of an even higher degree is not in yet. Key take away: Price is still impulsive to the downside.

This Publish Is Intended For Educational Purposes Only

IREN | DailyNASDAQ:IREN — Quantum Model Projection

Bullish Alternative 📈

IREN has appreciated ~70% since mid-December, launched decisively from the support

Q-Structure λₛ confluence.

This advance is projected as the initial phase of Intermediate Wave (5) within Primary Wave ⓷, potentially unfolding as an extension, with a Fib-extension target ➤ $431 🎯 (beyond the scope of the daily frame).

🔖 This bullish alternative structurally aligns with early Primary Wave ⓹ within Wave III of BTC ’s second Cycle.

🔖 This outlook is derived from insights within my Quantum Models framework. Within this methodology, Q-Targets represent high-probability scenarios generated by the confluence of equivalence lines. These Quantum Structures also serve as structural anchors, shaping the model's internal geometry and guiding the evolution of alternative paths as price action unfolds.

MSFT - Target 408-426 in last half of Apr 2026

MSFT good target price to load for long term is at support zone level 408-425 where there are huge volumes traded. I think it may reach that somewhere late Apr 2026 before its next earnings that time (sideway down a huge bull flag). This zone level is also right at the 200EMA of the weekly chart.

XAGUSD SILVER CYCLE 2020 - 2026With such significant upward price movements, Silver began its bullish trend in 2020.

And now, in 2026, Silver has broken through the 4,618 Fibonacci level.

Will Silver break through the 5,618 level? Given the continued strengthening, the possibility of breaking through that level still exists, around the 120s.

Let's continue to follow this extraordinary price movement.

Dow Jones (US30) Surges on Diplomatic BreakthroughThe Dow Jones index (US30) is displaying impressive buying strength. Market sentiment is driven by a major geopolitical shift: the cancellation of Trump’s tariffs on Europe in exchange for strategic agreements (Greenland). This diplomatic easing is unlocking massive growth potential for American companies.

📈 My Trading Plan:

Bias: Resolutely Bullish.

Buy Zone: Identified on the chart, where liquidity is maximized for a potential breakout.

Stop Loss (SL): H4 candle close below the zone. Discipline is key: if the zone breaks on a closing basis, the scenario is invalidated.

Take Profit (TP): Aiming for the all-time highs marked on the chart.

Key to Success: Patience and Discipline. We don't anticipate the move; we follow the structure.

Elise |XAUUSD | 30M – Bullish Continuation After Demand ReactionOANDA:XAUUSD

After a healthy pullback into demand, price printed a strong bullish reaction and resumed upside momentum. This move suggests continuation rather than exhaustion. As long as price holds above the demand zone, upside liquidity remains the preferred path.

Key Scenarios

✅ Bullish Case 🚀 → Continuation above demand can drive price toward external highs.

🎯 Target 1: 5000

🎯 Target 2: 5050

❌ Bearish Case 📉 → A sustained break and close below the demand zone would invalidate the bullish continuation and signal deeper correction.

Current Levels to Watch

Resistance 🔴: 5000 – 5050

Support 🟢: 4900 – 4860

⚠️ Disclaimer: This analysis is for educational purposes only. It is not financial advice. Please do your own research before trading.

WTI H4As anticipated in my previous analyses, WTI (Crude Oil) confirms its bullish momentum. The price structure validates buyer strength, supported by a tense geopolitical and energy landscape at the start of 2026.

📌 Key Analysis Points:

Bias Confirmation: The long-term vision remains intact. Price is respecting its supports and heading toward the major resistance levels identified on the chart.

Catalysts: Recent disruptions to energy infrastructure and rising global demand are pushing the barrel toward new highs.

Targets: Take Profit (TP) targets are clearly mapped on the chart. We are aiming for an extension of the current trend to sweep liquidity at the highs.

🛡️ Strategy: Patience has paid off. For those looking for entry points, watch for retests of Demand Zones on lower timeframes.

Golden Rule: Follow the plan, manage your risk, and let profits run toward the target zones.

BITCOIN CYCLE 2022 - 2025Below, I show the Bitcoin price cycle, since 2022 and reaching its peak in 2025.

In this chart, I use Fibonacci extensions as analysis to determine key levels within the Bitcoin cycle.

At the Fibonacci extension levels, we can see that the price reacts within these areas.

BTC is currently in a correction mode, and we can also see the possibility of a correction level and area being touched.

Hopefully, this is helpful!

SILVER $400 - UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY📣 Hello everyone!

Here is the global chart of XAG/USD and directly my long-term trading idea, time frame 1 month. Here is the story from 1802, but in fact this is not even a complete timeline.

I believe we are “close” to completing the Elliott Global Five on the silver chart. The first primary impulse wave, in my opinion, ended in 1864, the second corrective primary wave ended in 1932. From 1932 to 1980, the most powerful third Elliott wave of the primary level was formed - in 48 years, silver increased in price by 170 times. Then from 1980 to 1991 there was a bear market in the correctional wave-4 of the primary level. Further, from 1991 to the present day, the global impulse wave 5 of the primary level of the cycle has been developing.

Within the framework of my Elliott idea, we should expect that wave-5 of the primary level will be fully formed within 45-74 years, that is, from 2036 to 2065. Taking into account the dollar charts, US inflation, government bond yields and other important macroeconomic data, I am more inclined to believe that the cycle will end in 2036. Therefore, my goal is $400 per ounce of silver by 2036. This is an increase of approximately 18 times from the current price. This is great news for long-term investors.

As for this relatively short-term outlook for Silver, in the first half of 2024 there is still a chance, within the bullish flag, to descend to the zone of 14-16 dollars per ounce. Either way, I believe that in the longer term, silver is already incredibly close to breaking through its twelve-year downtrend resistance. As soon as the bullish flag and, accordingly, trend resistance are broken upward, then after a long period of consolidation, vigorous growth will begin and silver will quickly return to the highs of 2011. Be prepared for this.

❌ It is also necessary to understand that according to my current wave marking, under no circumstances should the price fall below $7.28, this is the completion level of wave 1 of the secondary level. If this happens, then it will be necessary to look for an error and make serious changes to the Elliott price movement marks in this trading idea.

⚠️ As always, I wish you good luck in making independent trading decisions and profit ✊

Goodbye!

AVAX Triple Zig-Zag FormationTriple Zig-Zag

It appears that AVAX has been forming a triple zig-zag correction on a high time frame. After further study of lower time frames, I have discovered smaller fractals of this correction of lower degrees. Price action is currently supported by the 1.272 pocket, which COULD lead to a reversal, but the1.618 (Wave "W" × 0.618) is a favored ratio above the 1.272 . However, there are crumbs on a lower time frame that suggest we may be experiencing another fractal of this structure.

On The 8-Hour Chart

An ABC correction has complete, and has price has become impulsive to the down side; the dominant trend has resumed. Price is currently in the Golden Window (0.618-0.786) retracement of wave B and in an area of high liquidity. Could this be a shakeout reversal pattern or continuation pattern? 👇👇👇

On the 1-Hour Chart

An exotic expanded running flat was printed that potentially marked wave 2 or B of a higher degree. Afterward came a 5 wave impulse down with a truncated 5th followed by an ABC to the upside. It's possible that we are in the middle of a zig zag correction and are waiting for confirmation of wave 2 of the potential 5 wave impulse down. An invalidation level would be @ $12.49 and would suggest that the high time frame triple zig zag may be complete at the 1.272 of wave "W". 👇👇👇

...if price action continues to the down side the 1.618 of wave A is a common area of retracement. The 1.272 ratio on the 1-Hour chart is also a potential retracement level, but less common than the 1.618.

This Publish Is Intended For Educational Purposes Only

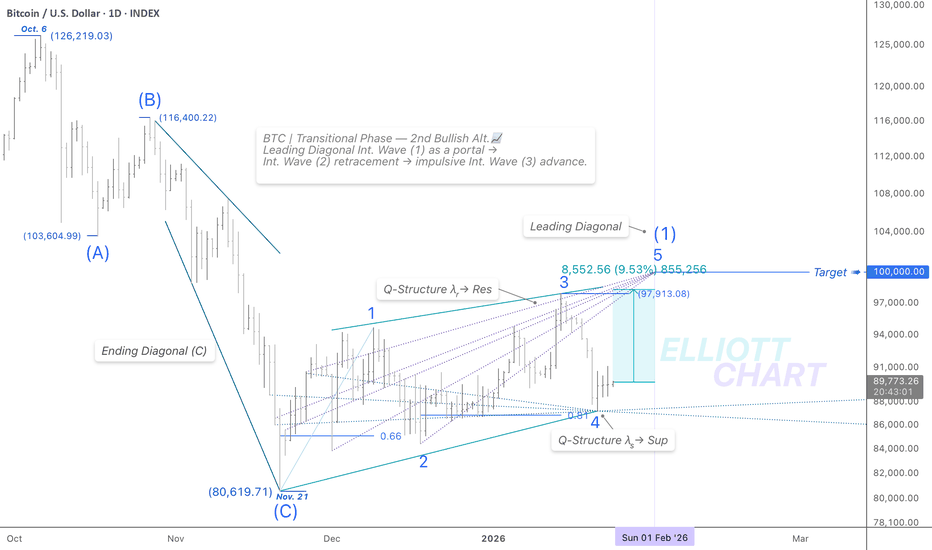

BTC | DailyCRYPTOCAP:BTC — Transitional Phase

BTC is holding above Q-Structure λₛ support.

A ~9.5% further advance is required to confirm the Leading Diagonal as a transitional structure in Intermediate Wave (1), signalling a Primary-degree trend reversal.

Q-Structure λᵣ targets ➤ $100k via Minor Wave 5(near term).

🔖 This outlook is derived from insights within my Quantum Models framework. Within this methodology, Q-Targets represent high-probability scenarios generated by the confluence of equivalence lines. These Quantum Structures also serve as structural anchors, shaping the model's internal geometry and guiding the evolution of alternative paths as price action unfolds.

#BTC #Bitcoin #ElliottWave #QuantumModel #CryptoMarkets

#MarketStructure #TrendReversal

XAUUSD GOLD Price Road Map 1970 - 2026In the early history of gold prices in the 1970s, we can see that prices were marked up as high as the 4.618 Fibonacci level until 1980.

Interestingly, in the current era, gold prices have been marked up since 2016, from 1040 to 2026, when they reached the 3.618 Fibonacci level.

Will history repeat itself ? Will prices be marked up to the 4.618 Fibonacci level ?

Let's continue to follow the history of gold prices from the 1960s to the present.

basic technical analysis : Fibonacci Extention.

We give our respect and thankful to Leonardo Pisano (Fibonacci).

I'm very happy to share this, and I hope it's helpful!

NOTE : correction for the early period 1960-1970 is a typo...I meant 1970 -1980 .

I am providing this note because the image cannot be edited.

Divergence Spotted! Wave C Power Play BeginsOn the Daily timeframe, price is currently forming an X wave within a WXYXZ complex correction.

This X wave is developing as a corrective structure, most likely a Running Flat or an Expanding Flat.

Waves A and B are completed, and the market is now progressing through wave C, whose purpose is to complete the X correction before a larger bullish continuation.

Due to the higher-timeframe structure, this C wave is expected to be strong and extended, implying several months of bearish pressure before the correction fully concludes.

:

Wave B has ended as a complex WXYXZ correction.

The final Z wave itself unfolded as:

a nested WXYXZ,

followed by an ending 12345 impulse.

A clear divergence between waves 4 and 5 marked the termination of wave B.

After this exhaustion, the market initiated wave C.

Wave C started with a clean 12345 impulsive structure, and price is currently developing wave 3 of C, which typically represents the strongest and fastest segment of the move.

The current bearish move is part of wave C of X on the Daily timeframe.

Once wave C completes, the larger correction (X) should be finished.

After that, the market is expected to resume higher toward wave Z, targeting the 1.414 – 1.618 Fibonacci extensions.

DXY (Dollar Index) 4H Outlook (Count 3)Here is a 4H update on the TVC:DXY index. I've been bearish for a while as you can see from my previous outlooks.

i think price in currently in a wave iii decline, i posted some chart images last night and the chart is playing out since then in line with the outlook.

previously posted weekly outlook shows the potential larger pattern at play.

If you like my analysis show your appreciation!!

SOL/USDT Approaching Key Demand – Bounce or Breakdown?Technical Analysis:

Price Structure: After printing a recent lower high, SOL is undergoing a sharp correction toward dynamic support levels.

Point of Control (POC): Based on the Volume Profile (VPVR), the $127.39 area is the current POC. The price is consolidating exactly at this high-volume node. If it fails to hold here, market gravity may pull it lower.

Support & Demand Zones:

Immediate Support: $127 (currently being tested).

Major Support: The red horizontal line at $116.71 aligns with the blue demand zone below ($110 - $115). This is the "last line of defense" for bulls to maintain the medium-term structure.

Resistance: The red horizontal line at $140 remains the primary obstacle. A daily candle close above this level is required to confirm a trend reversal.

Trading Plan:

Scenario A (Aggressive - Buy on Retest):

Entry: $125 - $127 area (look for confirmation like a pin bar or engulfing candle on lower timeframes).

Target: $140 (Resistance).

Stop Loss: Below $123.

Scenario B (Conservative - Buy at Major Support):

Entry: Wait for a dip to the $116.71 level. This area has a higher probability of a rebound as it served as a historical pivot point (see the yellow markers in Dec/Jan).

Target: $130 and $140.

Stop Loss: Below $110.

Note: Always use strict risk management. SOL's movement is heavily influenced by overall BTC market sentiment.

Disclaimer: This is a personal analysis and not financial advice. Trade at your own risk!

XAUUSD Update BULLISH ContinuationAfter hitting a new all-time high this week at 4990, gold prices are still strongly predicted to continue their bullish rally and break through the 5,000 area.

We'll follow this price movement and becareful when entering the market. Wait for a minor retracement, and avoid FOMO.

Have a blessing week ahead !

Nexgold Mining Daily Outlook Count 3This is my Elliott Wave count on Nexgold Mining TSXV:NEXG . Price could be making a wave 3 high and could retrace for wave 4. suppose it depends on what Gold does to a degree. The chart so far has reversed at some nice Fibonacci levels along the outlook.

The wave 5 high wouldn't necessarily be end of the bullish sequence, i just don't tend to project too far ahead, lets let these waves play out and go from there.

More comments on the chart.

If you like, show your appreciation!

Rose - a short-term recovery🐂 LONG – ROSE

On the 15m timeframe, price is consolidating above a strong resistance, signaling accumulation and preparation for a potential breakout. This move is likely a short-term recovery phase within the broader structure. The prevailing downtrend remains the key filter—entry is planned only after a confirmed break above the descending trendline, reducing false-breakout risk.

Momentum and structure align with typical pre-breakout behavior: compression near resistance, reduced volatility, and stabilizing price action. This setup supports a controlled long once confirmation is in place.

🎯 TP: 0.01929

🛡️ SL: 0.01640

📊 RR: 1 : 3.38

Trade thesis: confirmed trend break + resistance hold → short-term recovery with favorable risk–reward.