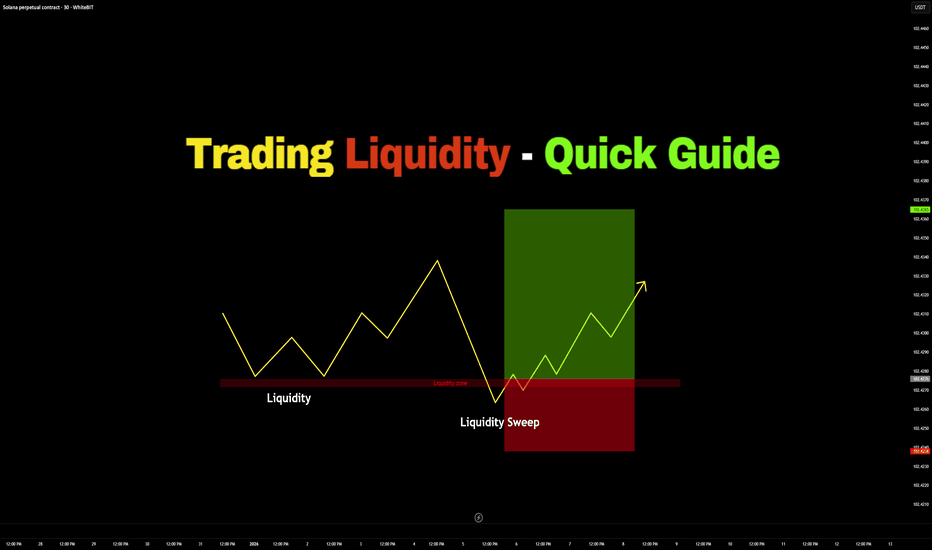

Trading Liquidity – Quick Guide in 5 StepsWelcome back everyone to another guide, today we will speed run "Trading Liquidity" in a quick 5 step guide. Be sure to like, follow and join the community!

1) Identify Liquidity:

- Equal highs or cluster of highs (Buy-side Liquidity)

- Equal lows or cluster of lows (Sell-side Liquidity)

- Obvious highs & lows

2) Identify Liquidity Direction (Price moves towards liquidity first):

- Equal highs > Price is likely to sweep above

- Equal lows > Price is likely to sweep below

3) Wait for Liquidity Sweeps

- Price takes out lows

- Stops get triggered

- Look for rejection or close back inside

Do NOT enter before the sweep or before the confirmation.

4) Enter Trade:

Enter after confirmation, away from liquidity

- Stop loss: Longs > Below Swept Lows

- Stop loss: Shorts > Above Swept Highs

5) Take Profits:

- Take Profit: Nearest opposing liquidity

- Take Profit: Previous high/low

- Take Profit: Range boundaries

RESULTS:

Liquidity sweep > confirmation > clean move

Thank you all so much for reading! Hopefully this is a useful guide in the future or present! If you would like me to make any simplified guides, articles or tutorials, let me know in the comment section down below - or even contact me through trading view.

Thank you!

Chart Patterns

Gold doesn’t hate you. Gold just loves… your liquidity.If you’ve ever felt like XAUUSD has a personal grudge against you — price spikes the moment you enter, sweeps your SL perfectly, then runs strongly in your predicted direction right after you exit — take a breath. Pause for a second.

The gold market doesn’t move based on emotions.

It moves based on liquidity — the fuel behind every major move .

1. Retail traders trade price. Institutions trade orderflow.

You look at the chart to find a perfect entry.

Institutions look at the chart to find where the most SL and pending orders are stacked.

To them, it’s not a “resistance zone” — it’s a liquidity pool.

When retail SL gets triggered, it turns into market orders.

And those market orders become the free matching engine for big players to enter without excessive slippage.

You think you’re protecting your risk with SL.

The market thinks you’re placing free orders for them to fill their positions.

2. Gold loves clean levels because SL sits at clean levels.

Liquidity sweep zones usually share the same traits:

- Recent highs/lows everyone can see

- Support/resistance that looks clean and easy to draw

- Attractive round numbers like 2,700 – 2,650 – 2,600…

These areas are liquidity magnets, not breakout signals.

3. “Sweep then run” is a process, not an exception.

A major gold move typically has 2 phases:

- Liquidity grab (SL sweep, pending activation)

- Expansion (the real trend begins)

Most traders lose because they confuse phase 1 with phase 2.

Retail sees a spike → fear trend break.

Institutions see a spike → mission accomplished, liquidity collected, positions filled.

4. The market doesn’t need you to be wrong — it only needs you forced out.

Gold doesn’t need to prove your analysis was bad.

It just needs enough volatility to make you:

- Hit SL

- Or close manually out of panic

Either way, the market gets the liquidity you left behind.

5. Trading maturity = not turning yourself into liquidity.

You don’t need to remove SL. You just need to:

- Place SL where the structure is truly invalidated, not where liquidity is obvious

- Enter after liquidity is swept, not before

- Keep margin to reposition during pullbacks

- Understand: being right isn’t enough — you must be right at the right time.

Gold Rewards Timing, Not Activity🟡 Gold Rewards Timing, Not Activity ⏳✨

Gold is not a market that rewards constant action.

It rewards waiting, observation, and precise timing.

Many traders believe that trading more means earning more. In Gold, this mindset often leads to overtrading, emotional decisions, and unnecessary losses.

⏱️ 1. Gold Moves in Phases, Not Constant Trends

Gold spends a large amount of time in:

consolidation 🔄

slow accumulation 🧩

controlled ranges 📦

During these phases, price appears “boring,” but the market is actually preparing.

Trading aggressively in these conditions usually means trading noise, not opportunity.

🧠 2. Activity Feeds Emotions, Timing Controls Risk

High activity leads to:

impatience 😤

forced entries 🎯

emotional exits ❌

Good timing, on the other hand, comes from:

understanding context 🧭

waiting for price to show intent 📊

acting only when conditions align ✅

Gold punishes impatience faster than most markets.

🏦 3. Institutions Trade Less, But Trade Better

Large players do not chase every candle.

They wait for:

liquidity to build 💧

weak hands to exit 🧹

price to reach meaningful zones 📍

When timing is right, Gold often moves fast and decisively — leaving overactive traders behind.

⚡ 4. Big Gold Moves Come After Quiet Periods

Some of the strongest Gold expansions begin after:

low volatility 😴

reduced participation 📉

trader boredom 💤

This is why patience is not passive — it is strategic.

🧩 Key Insight

In Gold, doing less at the right time often outperforms doing more at the wrong time.

🎯 Final Takeaway

❌ More trades ≠ more profits

✅ Better timing = cleaner execution

🟡 Gold rewards discipline, context, and patience

Master timing, and activity will take care of itself.

The Liquidity Map: How Smart Money Actually Moves

Price Doesn't Move Randomly — It Hunts Liquidity

Every time you place a stop loss, you're adding to a liquidity pool.

Every time price "randomly" spikes to hit your stop before reversing, it wasn't random at all.

Understanding liquidity is understanding why price moves the way it does — and AI is getting very good at mapping these invisible pools.

---

What Is Liquidity?

Simple Definition:

Liquidity is the ability to buy or sell without significantly moving the price.

In Practice:

Liquidity exists where orders are clustered:

Stop losses (become market orders when triggered)

Limit orders (resting buy/sell orders)

Pending orders (orders waiting to execute)

The Key Insight:

Large players need liquidity to fill their positions. They can't just buy 10,000 contracts at market — they need someone to sell to them.

Where do they find sellers? Where stop losses are clustered.

---

Types of Liquidity Zones

1. Buy-Side Liquidity (BSL)

Located ABOVE price action:

Stop losses from short positions

Buy stop orders from breakout traders

Triggered when price moves up

2. Sell-Side Liquidity (SSL)

Located BELOW price action:

Stop losses from long positions

Sell stop orders from breakdown traders

Triggered when price moves down

3. Equal Highs/Lows

Multiple touches at the same level:

Creates obvious stop placement

Attracts more orders over time

High-probability liquidity targets

4. Swing Points

Previous highs and lows:

Natural stop loss placement zones

Visible to all market participants

Frequently targeted before reversals

---

Why Price "Hunts" Liquidity

The Mechanism:

Retail traders place stops at obvious levels

These stops accumulate into liquidity pools

Large players need this liquidity to fill positions

Price is drawn to these pools

Stops trigger, providing liquidity

Large players fill their orders

Price reverses

This Isn't Conspiracy — It's Market Structure

Large orders need counterparties. If a fund wants to buy 50,000 shares, they need 50,000 shares worth of sellers. Stop losses, when triggered, become market sell orders — perfect liquidity for buyers.

---

How AI Maps Liquidity Zones

Method 1: Swing Point Detection

AI identifies:

Recent swing highs (potential BSL)

Recent swing lows (potential SSL)

Multiple touches at same level (stronger zones)

Method 2: Order Flow Analysis

Where available, AI analyzes:

Resting limit orders in the book

Historical order placement patterns

Volume profile at price levels

Method 3: Pattern Recognition

AI identifies formations that create liquidity:

Equal highs/lows (obvious stops)

Trendline touches (stops below/above)

Range boundaries (stops outside range)

Method 4: Historical Stop Placement

Machine learning on:

Where stops typically cluster relative to patterns

How far from entry traders usually place stops

Common ATR multiples for stop distance

---

Liquidity Concepts in Practice

Concept 1: Liquidity Sweep

Price moves to take out a liquidity zone, then reverses.

Identification:

Price breaks above/below a key level

Quick rejection (wick or immediate reversal)

Often accompanied by volume spike

Trading Application:

Wait for the sweep before entering in the opposite direction.

---

Concept 2: Liquidity Void (Fair Value Gap)

Areas where price moved so fast that no trading occurred.

Identification:

Gap between candle bodies

No overlap in price action

Often created during news or high momentum

Trading Application:

Price often returns to fill these voids before continuing.

---

Concept 3: Liquidity Grab

Intentional move to trigger stops before the real move.

Identification:

Sharp move into obvious stop zone

Immediate reversal

Often occurs before significant moves

Trading Application:

Don't place stops at obvious levels. Wait for grabs before entering.

---

Building a Liquidity-Aware Strategy

Step 1: Identify Key Levels

Mark on your chart:

Recent swing highs (BSL zones)

Recent swing lows (SSL zones)

Equal highs/lows

Obvious trendline touches

Step 2: Anticipate Liquidity Hunts

Before entering, ask:

Where is the nearest liquidity pool?

Is price likely to sweep that level first?

Should I wait for the sweep?

Step 3: Place Stops Intelligently

Instead of obvious levels:

Beyond the liquidity zone (not at it)

Use ATR-based stops that adapt to volatility

Consider time-based exits instead of price-based

Step 4: Use Liquidity as Entry Trigger

Enter AFTER liquidity is taken:

Wait for sweep of key level

Confirm with reversal candle or structure

Enter with stop beyond the sweep

---

Common Liquidity Mistakes

Placing Stops at Round Numbers — $100, $50, $10 — everyone sees these. So does the algorithm hunting stops.

Stops Just Below Support — If you can see the support, so can everyone else. Stops cluster just below.

Ignoring the Sweep — Entering at support without waiting for the liquidity grab often means getting stopped out on the sweep.

Fighting Liquidity Flow — If price is clearly hunting liquidity in one direction, don't stand in front of it.

---

AI-Enhanced Liquidity Trading

What AI Can Do:

Map All Liquidity Zones — Scan multiple timeframes and instruments simultaneously

Rank Zone Importance — Weight zones by age, touches, and volume

Predict Sweep Probability — Based on current momentum and zone proximity

Alert on Sweeps — Real-time notification when liquidity is taken

Optimize Stop Placement — Calculate stops that avoid obvious liquidity pools

---

Liquidity Zone Checklist

Before entering any trade:

Where is the nearest BSL (above price)?

Where is the nearest SSL (below price)?

Has recent liquidity been swept?

Is my stop at an obvious level?

Am I entering before or after the liquidity grab?

---

Key Takeaways

Liquidity zones are where stop losses and pending orders cluster

Price is drawn to liquidity — large players need it to fill positions

AI can map and rank liquidity zones across multiple timeframes

Smart traders wait for liquidity sweeps before entering

Stop placement should avoid obvious liquidity pools

---

Your Turn

Have you noticed price "hunting" your stops before reversing?

How do you currently think about liquidity in your trading?

Share your experiences below 👇

Options Blueprint Series [Advanced]: Structuring Long VolatilityWhy Long Volatility Matters in Euro FX Right Now

Euro FX futures offer a clean and highly liquid way to observe how macro forces, relative growth expectations, and monetary policy differentials express themselves through price. While directional narratives often dominate discussion, options markets frequently reveal a different story — one centered on volatility pricing rather than directional certainty.

This Options Blueprint focuses on Euro FX futures (6E) and Micro EUR/USD futures (M6E) during a period when implied volatility is historically compressed, while price structure suggests an elevated probability of expansion. The purpose of this case study is not to anticipate direction, but to explore how options structures can be engineered to respond to range resolution risk when price compression and technical conflict coexist.

This article is strictly educational and illustrative, designed to demonstrate principles of volatility analysis, options structure design, and risk management.

Volatility Context: Reading Implied Volatility with CVOL

Implied volatility reflects the market’s collective expectation of future price variability. When implied volatility is elevated, options tend to price in larger potential moves. When it is compressed, options reflect an assumption of relative calm.

In this case, the CVOL index for Euro FX futures is observed at relatively low levels compared to its behavior earlier in the year. While CVOL is not predictive, it provides valuable context: the market is currently assigning a lower probability to large price swings than it has at other times.

Periods of compressed implied volatility are noteworthy because price expansion often follows periods of contraction, particularly when price structure begins to show signs of instability. This does not guarantee movement, but it shifts the analytical focus toward strategies that can benefit from expansion rather than stagnation.

Technical Landscape: A Market at an Inflection Point

From a structural perspective, Euro FX futures present a rare but important configuration: conflicting continuation and reversal patterns.

A bullish flag has developed following an impulsive advance, suggesting the potential for trend continuation.

Simultaneously, a double top formation has emerged, introducing the possibility of a downside resolution.

When viewed in isolation, each pattern offers a directional narrative. When viewed together, they create directional ambiguity but expansion risk clarity. In other words, the market may not be signaling where it intends to go — but it is signaling that remaining stagnant may be increasingly difficult.

This type of structural conflict is often where volatility-focused strategies become more relevant than directional trades.

Mapping Price Targets to Market Structure

Technical patterns are most useful when they provide reference points, not predictions. In this case, both patterns generate projected levels that act as structural guideposts.

The bullish flag projects an upside objective near 1.2116, which also aligns with a clearly defined UFO resistance zone.

The double top projects a downside objective near 1.1618, aligning with a well-defined UFO support zone.

These levels form a structural range boundary. Price acceptance beyond either boundary would represent meaningful resolution of the current compression phase. For options traders, these projected zones are valuable because they provide logical strike selection reference points when designing volatility structures.

Strategy Foundation: The Role of a Long Straddle

A traditional long straddle involves purchasing both a call and a put at the same strike, typically near the current price. This structure is directionally neutral and benefits from large price movements in either direction.

The strength of a long straddle lies in its convexity. Its primary weakness lies in time decay, particularly when implied volatility is low and price remains range-bound.

In compressed volatility environments, a pure long straddle can be inefficient if price takes time to resolve. This is where structure refinement becomes essential.

Strategy Evolution: Structuring an Asymmetric Long Volatility Approach

Instead of relying on a textbook long straddle, this Options Blueprint explores an asymmetric volatility structure designed to reflect the underlying technical landscape.

The structure begins with a long at-the-money straddle, capturing core volatility exposure:

Long 1.175 Call

Long 1.175 Put

To refine the payoff and reduce exposure to time decay, options are sold at technically

meaningful projected targets:

Short 1.21 Call

Short 1.16 Put

This transforms the strategy into a defined-risk, asymmetric volatility structure.

Key educational concepts illustrated by this construction:

The long options capture expansion risk near the current price.

The short options align with projected structural boundaries.

The payoff becomes skewed, favoring upside expansion while still allowing for limited downside participation.

Theta exposure is reduced compared to a pure long straddle.

The goal is not optimization, but intentional payoff shaping based on structure.

Risk Profile Analysis: Understanding the Payoff Diagram

The resulting risk profile highlights several important principles.

Maximum risk occurs if price remains trapped between the short strikes into expiration.

Upside expansion toward the upper projected level produces the most favorable outcome.

Downside expansion produces a smaller, but still positive, outcome.

Both risk and reward are defined, removing uncertainty around extreme scenarios.

This structure favors movement over stagnation, reflecting the belief that expansion risk outweighs the likelihood of prolonged consolidation — without requiring directional conviction.

Contract Specifications

Euro FX futures are available in both standard and micro formats.

o 6E (Euro FX Futures)

Larger notional exposure

Suitable for accounts with higher margin tolerance

o M6E (Micro EUR/USD Futures)

One-tenth the size of the standard contract

Greater flexibility for position sizing

Often useful for testing or scaling strategies

Both contracts reference the same underlying market structure, allowing the same analytical framework to be applied across different risk profiles.

Margin requirements vary and are subject to change, making position sizing and risk definition essential considerations when selecting between standard and micro contracts.

Euro FX futures (6E) have a tick size of 0.000050 per Euro increment = $6.25 tick value and currently require roughly ~$2,700 in margin per contract, while Micro EUR/USD Futures (M6E) use a 0.0001 tick size per euro = $1.25 tick value and margin closer to ~$270.

Risk Management Considerations

Options strategies are not defined solely by payoff diagrams — they are defined by how risk is managed over time.

Key considerations include:

Sizing positions so that the maximum loss is acceptable within the broader portfolio context.

Understanding how time decay accelerates as expiration approaches.

Recognizing that volatility expansion does not occur on a fixed schedule.

Accepting predefined loss zones as part of the structure rather than reacting emotionally.

Risk management is not about avoiding losses; it is about controlling exposure to uncertainty.

Key Takeaways from This Options Blueprint

Implied volatility provides context, not direction.

Conflicting chart patterns often increase expansion risk.

Options structures can be shaped to reflect technical asymmetry.

Modifying classic strategies can improve alignment with market conditions.

Defined risk and intentional design matter more than prediction.

This case study demonstrates how volatility, structure, and risk management intersect — without requiring directional forecasts.

Data Consideration

When charting futures, the data provided could be delayed. Traders working with the ticker symbols discussed in this idea may prefer to use CME Group real-time data plan on TradingView: www.tradingview.com - This consideration is particularly important for shorter-term traders, whereas it may be less critical for those focused on longer-term trading strategies.

General Disclaimer

The trade ideas presented herein are solely for illustrative purposes forming a part of a case study intended to demonstrate key principles in risk management within the context of the specific market scenarios discussed. These ideas are not to be interpreted as investment recommendations or financial advice. They do not endorse or promote any specific trading strategies, financial products, or services. The information provided is based on data believed to be reliable; however, its accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. Trading in financial markets involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Each individual should conduct their own research and consult with professional financial advisors before making any investment decisions. The author or publisher of this content bears no responsibility for any actions taken based on the information provided or for any resultant financial or other losses.

The Language of Price | Lesson 15 – Chart Patterns TheoryLesson Focus: Chart Pattern Types (Theory)

This educational chart explains what chart patterns are and how they are used as visual tools to understand market structure and historical price behavior.

Chart patterns do not predict or cause price movement.

They visually represent past interactions between buyers and sellers , helping us observe how market participation has previously behaved at certain price areas.

📌 WHAT IS A CHART PATTERN?

A chart pattern is a recurring price structure that forms as a result of:

• buying and selling pressure

• price compression or expansion

• repeated market reactions at specific price zones

Chart patterns are descriptive, not predictive.

They are used to study historical market behavior , not to provide trading instructions.

📊 TYPES OF CHART PATTERNS USED IN THIS EDUCATION

Double Top

A price structure where the market fails twice to continue higher, often reflecting increased selling pressure near a resistance area.

Double Bottom

A structure where price finds support twice at a similar level, showing repeated buying interest in the same price zone.

Rising Wedge

A contracting structure where price moves upward with decreasing momentum, illustrating gradual loss of bullish pressure.

Falling Wedge

A downward contracting structure that reflects weakening selling pressure over time.

Ascending Triangle

A pattern formed by rising lows and a horizontal resistance, showing increasing demand at higher price levels.

Descending Triangle

A pattern with falling highs and horizontal support, representing persistent selling pressure against a fixed price area.

Symmetrical Triangle

A balanced price compression where buying and selling pressure converge, indicating market indecision and reduced volatility.

Ascending Channel

A structured upward price movement within parallel boundaries, reflecting controlled bullish participation.

Descending Channel

A structured downward movement within parallel boundaries, showing controlled bearish participation.

Horizontal Channel

A range-bound structure where price moves sideways, representing temporary equilibrium between buyers and sellers.

🧩 KEY EDUCATIONAL CONCEPT

Candlesticks and chart patterns do not move price.

They reflect historical decisions made by market participants.

Market structure becomes clearer when we focus on:

• price interaction zones

• pressure buildup and release

• collective participant behavior

rather than treating patterns as standalone decision tools.

📘 SERIES NOTE

This lesson introduces the theoretical foundation of chart patterns.

Practical examples will follow in the next lessons.

If you find this educational series useful, you may follow the profile to continue exploring market structure concepts step by step.

ETHICAL & EDUCATIONAL NOTICE

This content is presented solely for educational and analytical purposes , based on historical price data.

It does not promote or encourage any specific trading method, financial instrument, gambling, leverage, margin usage, short selling, or interest-based activity .

Readers are encouraged to align any financial activity with their own ethical, legal, and religious principles .

⚠️ DISCLAIMER

This material is strictly educational and informational .

It does not constitute financial advice, investment recommendations, or trading instructions.

The author does not provide personalized guidance.

Any decisions made based on this content are the sole responsibility of the individual.

The Language of Price | Lesson 14 –Candlesticks + S&R Practice 3Educational Context

This lesson is a practical continuation of the previous ranging market theory.

It demonstrates how Candlesticks and Support & Resistance interact inside a balanced (range-bound) market using real-chart illustrations.

↔️ Price oscillates between boundaries

⬆️ Upper boundary → Resistance

⬇️ Lower boundary → Support

The objective is to improve structural reading and price behavior awareness , not prediction.

Scenario 1 – Fresh Resistance Reaction

⬆️ Resistance

• Fresh formed

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Inverse long wick

• Inside candle

• Momentum

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Price pushes up ⬆️ into resistance

↳ Upper rejection appears 🛑

↳ Inside candle reflects hesitation

↳ Momentum slows near the range ceiling

📌 Range structure remains intact

Scenario 2 – Fresh Support With Strong Reaction

⬇️ Support

• Fresh formed

• Huge move away

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Change color

• Inverse long wick

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Price drops into support ⬇️

↳ Strong rejection triggers displacement

↳ Color change signals shift in pressure

↳ Market responds decisively from the range low

📌 Support validated structurally

Scenario 3 – Resistance With Two Rejections

⬆️ Resistance

• 2 rejections

• Fresh formed

• Swing high

• Huge move away

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Shrinking candles

• 2 inverse long wicks

• Change color

• Momentum

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Price fails twice at resistance 🔁

↳ Shrinking candles show reduced buying

↳ Rejections confirm supply dominance

↳ Momentum aligns with range rejection

📌 Resistance becomes structurally respected

Scenario 4 – Support With Two Rejections

⬇️ Support

• 2 rejections

• Fresh formed

• Swing low

• Huge move away

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Shrinking candles

• 2 inverse long wicks

• Long wick

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Multiple failures to break support ⛔

↳ Wicks show absorption of selling

↳ Price reacts strongly away from the zone

↳ Range floor remains protected

📌 Balance maintained inside the range

Scenario 5 – Resistance With Three Rejections

⬆️ Resistance

• 3 rejections

• Fresh formed

• Swing high

• Huge move away

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Long wick

• Inside candle

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Repeated rejection at the same level 🔒

↳ Long wicks show persistent selling pressure

↳ Inside candle highlights consolidation at supply

↳ No breakout confirmation present

📌 Range ceiling clearly defined

Scenario 6 – Support With Three Rejections

⬇️ Support

• 3 rejections

• Fresh formed

• Swing low

• Huge move away

🕯️ Candlesticks

• Long wick

• Momentum

🧠 Illustrated Interpretation

↳ Price repeatedly rejected below support ⛔⬇️

↳ Strong reactions confirm demand presence

↳ Momentum supports continuation inside the range

📌 Support acts as a stable balance zone

Key Educational Insight

🧩 Candlesticks → describe reaction

📐 Support & Resistance → define boundaries

➡️ In ranging markets, context matters more than direction .

ETHICAL & EDUCATIONAL NOTICE

This content is presented solely for educational and analytical purposes , based on historical price data.

It does not promote or encourage any specific trading method, financial instrument, gambling, leverage, margin usage, short selling, or interest-based activity .

Readers are encouraged to align any financial activity with their own ethical, legal, and religious principles .

⚠️ DISCLAIMER

This material is strictly educational and informational .

It does not constitute financial advice, investment recommendations, or trading instructions.

The author does not provide personalized guidance.

Any decisions made based on this content are the sole responsibility of the individual.

EURUSD x DXY | Simple but Powerful EURUSD x DXY | Simple but Powerful

EURUSD confirms trend reversal

(Dowtrend break → structure shift → retest AOI)

DXY confirms trend weakness

(Uptrend break → higher low broken → AOI retest)

📌 Correlation is clear:

Weak DXY = Strength on EURUSD

🔎 Bias from Daily,

⏱ Entries only on lower timeframes with confirmation.

Simple structure. Smart patience. 💪📊

Same scenario repeating…

Do you see it too? 👀

DXY frame 1D

EURUSD frame 1D

the Fed faces another slew of challenges in the year aheadThe Federal Reserve heads into 2026 facing a slew of political and policy challenges, headlined by a new chair and an economy fed by both tailwinds and headwinds that will make policymakers’ choices all the more important.

Coming off three consecutive interest rate cuts, the central bank is expected to follow a more tepid path for the year ahead in which additional cuts could be hard to come by considering expectations for solid growth and ongoing inflation pressures.

One thing does seem certain: After a year of extraordinary upheaval surrounding the Fed, 2026 looks to offer more of the same.

“I do think there’ll be a big spotlight. There’ll be lots of intrigue,” said Kathy Bostjancic, chief economist at Nationwide. “There’s still a lot of uncertainty that keeps the Fed in the spotlight, and probably in the hot seat too.”

The previous year saw the Fed come under that spotlight in ways that it never had before.

As he started his second term at the White House, President Donald Trump repeatedly threatened to fire Fed Chair Jerome Powell for not being quicker to push for interest rate cuts. Around mid-year, the Fed came under fire again, this time for cost overruns at a renovation project it had undertaken at its Washington headquarters.

In between, Trump tried to remove Governor Lisa Cook over allegations — as yet unproven and not even brought as formal charges — that she committed mortgage fraud. That all came against a backdrop of who would succeed Powell as chair when his term expires in May, with as many as 11 candidates considered during an interview process led by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent.

If all that sounds exhausting, consider that 2026 begins with a Supreme Court hearing scheduled for Jan. 21 to decide whether Trump has the authority to remove Cook. A week later, the Federal Open Market Committee holds its interest rate vote. At some point during the month, Trump is expected to unveil his choice for Fed chair. And Powell, cagey on the issue so far, also will have to disclose whether he plans on serving out his term on the Board of Governors that runs until January 2028.

There also have been multiple dissents at recent rate votes, and new regional presidents set to come on board at the FOMC have a hawkish bent, meaning they’re likely to resist additional cuts.

“It’s still a tough spot for the Fed,” Bostjancic said.

Focus on policy

Still, when it comes to policy, most on Wall Street expect the Fed to put the noise in the background and continue down the road of lowering its benchmark interest rate just a bit more until it gets closer to a neutral level around 3%. Neutral is considered a spot that neither boosts nor holds back economic activity, and the funds rate is just half a percentage point above where most on the FOMC see the rate landing over the long term.

“Chair Powell helped orchestrate three 25-basis-point rate cuts in a row. It’s not as if he was standing in the way of the FOMC cutting rates,” Bostjancic said. As far as further cuts go, “For us, it’s the economic data.”

Bostjancic sees the data pointing to two cuts this year, one around mid-year and another toward the end. The Fed’s “dot plot” grid of expectations indicates just one cut, while outliers such as Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi and Citigroup seeing labor market weakness pointing to three.

Powell and his colleagues have stood by the notion that they won’t be bullied into cuts and indeed will be guided by data.

Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, thinks the economy will be too strong for the Fed to cut much more, seeing just one reduction ahead.

“The issue is that the winds are really changing for the U.S. economy,” Slok said during a CNBC interview Friday.

Whereas 2025 saw headwinds of tariffs, inflation and a general air of uncertainty, fiscal stimulus and a stabilizing labor market will be pushing on growth, he said.

“It is, in my view, looking like more that the tailwinds are beginning to accumulate and making it more difficult for the Fed to cut rates this year,” Slok added.

The role of AI

One wildcard will be the role that artificial intelligence plays on economic growth.

Seen as both a productivity enhancer and a potential impediment to hiring, assessing the impact AI is having on the economy will be paramount for the Fed, said Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM.

“The Fed this year has got a real challenge in terms of communicating their strategy,” Brusuelas said. “We have this massive investment flowing into very sophisticated technologies, and the Federal Reserve is going to need to communicate their basic view on what this means.”

After sputtering at the beginning of 2026, the economy grew rapidly in the middle two quarters and is on pace to accelerate at a 3% pace in the fourth quarter, according to preliminary data from the Atlanta Fed.

In addition to helping push along the broader economy, AI-related stocks were a key highlight of another stellar year on Wall Street that saw major averages post double-digit increases.

Calibrating monetary policy in that kind of environment will be tough, Brusuelas said.

“They’re going to need to provide strategic direction for the central bank at a time when the economy is clearly pivoting towards the integration of this sophisticated technology in the production of goods and provision of services,” he said. “This is a really big potential pivot around policy that needs to happen.”

Exotic Option Structured ProductsAdvanced Instruments for Customized Risk–Return Profiles

Exotic option structured products are sophisticated financial instruments designed by combining traditional securities with exotic derivatives to create customized payoff structures. Unlike plain vanilla options such as simple calls and puts, exotic options embed complex features—path dependency, multiple underlying assets, conditional triggers, or non-standard expiration rules. When these options are packaged into structured products, they offer tailored solutions to investors seeking specific risk–return outcomes, yield enhancement, capital protection, or exposure to particular market views.

Understanding Structured Products

Structured products are pre-packaged investment strategies, typically issued by banks or financial institutions, whose returns depend on the performance of one or more underlying assets such as equities, indices, interest rates, commodities, or currencies. They are usually composed of two main components:

A fixed-income element (such as a bond or zero-coupon bond) that provides capital protection or income stability.

A derivative component (options or swaps) that delivers market-linked returns.

When exotic options are used instead of standard options, the product becomes an exotic option structured product. These structures allow issuers to engineer highly specific payoff profiles that cannot be easily replicated through direct market trading.

What Makes an Option “Exotic”?

Exotic options differ from vanilla options in their payoff complexity and conditions. Some defining characteristics include:

Path dependency: Payoff depends on the entire price path of the underlying, not just the final price.

Conditional triggers: Activation or deactivation occurs if certain price levels are touched.

Multiple underlyings: Returns may depend on the worst-performing or best-performing asset in a basket.

Non-standard settlement: Payoffs may occur at multiple observation dates or vary dynamically.

Examples of exotic options include barrier options, digital options, Asian options, lookback options, and rainbow options.

Common Types of Exotic Option Structured Products

Barrier-Linked Structured Notes

These products embed barrier options, where the payoff depends on whether the underlying asset crosses a predetermined barrier level.

Knock-in structures activate only if the barrier is breached.

Knock-out structures terminate if the barrier is breached.

Such products are often used to enhance yield but expose investors to sudden changes in risk if the barrier is touched.

Autocallable Structured Products

Autocallables are among the most popular exotic structured products. They include periodic observation dates. If the underlying asset trades above a predefined level on any observation date, the product automatically redeems early, paying a fixed coupon.

These products are attractive in sideways or moderately bullish markets but can expose investors to significant downside risk in sharp market declines.

Range Accrual Notes

Returns accrue only when the underlying asset remains within a specified price range. The longer the asset stays within the range, the higher the coupon earned.

These products are sensitive to volatility and are suitable when investors expect stable market conditions.

Worst-of and Best-of Structures

These products depend on the performance of multiple underlying assets.

Worst-of structures base returns on the poorest-performing asset in the basket, increasing risk but offering higher coupons.

Best-of structures benefit from the strongest performer but usually offer lower yields.

Digital and Binary Payoff Products

Digital structures pay a fixed amount if a specific condition is met (for example, the index closes above a strike level at maturity), and nothing otherwise.

They provide clear outcomes but involve all-or-nothing risk profiles.

Why Investors Use Exotic Option Structured Products

Exotic option structured products are used for several strategic reasons:

Yield Enhancement: In low-interest-rate environments, these products offer higher potential returns than traditional bonds by selling optionality.

Market View Expression: Investors can express nuanced views such as range-bound markets, mild bullishness, or low volatility expectations.

Customization: Products can be tailored to specific investment horizons, risk tolerance levels, and underlying assets.

Capital Protection (Partial or Conditional): Some structures provide capital protection unless certain adverse conditions occur.

Risks Involved in Exotic Structured Products

Despite their attractiveness, exotic option structured products carry significant risks:

Complexity Risk

The payoff mechanics are often difficult to understand, making it hard for investors to assess true risk exposure.

Market Risk

Adverse movements in the underlying asset can lead to partial or full capital loss, especially in barrier or worst-of structures.

Issuer Credit Risk

Structured products are typically unsecured obligations of the issuing bank. If the issuer defaults, investors may lose their investment regardless of market performance.

Liquidity Risk

Secondary market liquidity can be limited. Exiting the product before maturity may result in unfavorable pricing.

Model and Volatility Risk

Exotic options are highly sensitive to volatility, correlation, and pricing models. Changes in these parameters can significantly affect valuation.

Pricing and Valuation Considerations

Pricing exotic option structured products involves advanced quantitative models. Unlike vanilla options, which can often be priced using closed-form solutions, exotic options typically require numerical methods such as Monte Carlo simulations or lattice models.

Key factors influencing pricing include:

Implied volatility and volatility skew

Correlation between multiple underlyings

Interest rates and dividend assumptions

Frequency of observation dates

Barrier proximity and probability of breach

Because of this complexity, investors often rely on issuer-provided pricing, which may include embedded margins.

Role in Portfolio Construction

Exotic option structured products are generally used as satellite investments rather than core holdings. They can complement a portfolio by:

Generating income during low-growth phases

Providing differentiated return streams

Enhancing yield without full equity exposure

However, prudent allocation sizing and diversification across issuers and structures are essential to manage concentration risk.

Regulatory and Suitability Aspects

Given their complexity, regulators in many jurisdictions require enhanced disclosure and suitability assessments before these products are sold to retail investors. They are more commonly used by high-net-worth individuals, institutional investors, and professional traders who understand derivatives and structured payoffs.

Conclusion

Exotic option structured products represent the intersection of financial engineering, derivatives pricing, and customized investment solutions. They offer powerful tools for tailoring risk and return, expressing precise market views, and enhancing yield. However, these benefits come with increased complexity, opacity, and risk. Successful use of exotic option structured products requires deep understanding of derivative mechanics, careful assessment of issuer creditworthiness, and disciplined risk management. For informed investors, they can be valuable instruments—but they demand respect, due diligence, and strategic intent rather than speculative use.

Currency Trading ExposedThe Foundation of Currency Trading

At its core, currency trading involves the exchange of one currency for another. Every trade is quoted in pairs, such as EUR/USD, USD/JPY, or GBP/INR. When a trader buys a currency pair, they are buying the base currency and simultaneously selling the quote currency. Exchange rates fluctuate continuously based on supply and demand, reflecting economic strength, capital flows, interest rates, and geopolitical confidence.

Unlike stock markets, forex is decentralized. There is no single exchange. Instead, trading occurs electronically over-the-counter (OTC) through a global network of banks, institutions, brokers, and traders operating 24 hours a day, five days a week. This structure provides unmatched liquidity but also makes regulation and transparency uneven across regions.

Who Really Moves the Currency Market

A common myth is that retail traders drive currency prices. In reality, retail participation represents only a tiny fraction of total volume. The true market movers include:

Central Banks, which influence currencies through interest rates, monetary policy, and direct interventions

Commercial Banks and Financial Institutions, executing large transactions for clients and proprietary desks

Corporations, hedging currency risk arising from international trade

Hedge Funds and Asset Managers, deploying macro and speculative strategies

Governments and Sovereign Funds, managing reserves and capital flows

Retail traders operate on the margins, reacting to price movements rather than creating them. Understanding this power imbalance is crucial for realistic expectations.

What Drives Currency Prices

Currency values are shaped by a combination of fundamental, technical, and sentiment-based factors.

Fundamentally, interest rate differentials are among the most powerful drivers. Capital tends to flow toward countries offering higher real returns, strengthening their currencies. Inflation data, GDP growth, employment numbers, trade balances, and fiscal stability also play major roles.

Technically, forex markets are highly responsive to price levels, trends, support and resistance, and market structure. Because of high liquidity and institutional participation, technical analysis often works effectively—especially on higher time frames.

Sentiment reflects how market participants collectively feel about risk. In times of global uncertainty, traders flock to safe-haven currencies such as the US dollar, Japanese yen, or Swiss franc. During risk-on phases, capital shifts toward emerging market and high-yield currencies.

The Truth About Leverage

One of the most “exposed” realities of currency trading is leverage. Forex brokers offer extremely high leverage, sometimes up to 1:500. While leverage magnifies potential profits, it also magnifies losses—often wiping out accounts faster than traders expect.

Many beginners are attracted by the ability to control large positions with small capital, but this is where the market becomes unforgiving. Without disciplined risk management, leverage turns forex trading into a probability-defying gamble rather than a strategic endeavor. Professional traders focus on capital preservation first, using leverage cautiously and consistently.

Retail Trading vs Institutional Reality

Retail forex education often promotes indicators, signals, and short-term strategies promising quick returns. Institutional traders, however, operate very differently. They focus on:

Macro-economic themes

Interest rate cycles

Order flow and liquidity zones

Risk-adjusted returns over long horizons

This mismatch between retail expectations and institutional reality explains why a majority of retail traders struggle. Currency trading is not about predicting every move—it is about managing uncertainty, probabilities, and drawdowns over time.

Psychology: The Silent Market Force

Currency trading exposes traders not just to markets, but to themselves. Fear, greed, impatience, and overconfidence are amplified in a fast-moving, leveraged environment. Many losses are not due to poor analysis, but poor emotional control.

Successful traders develop routines, predefined risk rules, and the ability to accept losses without emotional reaction. The mental discipline required in forex often exceeds that needed in slower-moving markets.

Opportunities That Still Exist

Despite the challenges, currency trading offers genuine opportunities. High liquidity ensures tight spreads in major pairs. The 24-hour nature allows flexibility across time zones. Strong trends can develop around monetary policy shifts, economic cycles, and geopolitical changes.

For informed traders, currencies also serve as tools for hedging, diversification, and global macro positioning. When approached with realistic expectations, solid education, and patience, forex trading can become a professional skill rather than a speculative trap.

Currency Trading Exposed: The Bottom Line

Currency trading is neither a shortcut to wealth nor an impossible game. It is a highly competitive, institution-driven market where success depends on knowledge, discipline, and risk control. Exposing the reality behind forex removes the illusion of easy money and replaces it with a clearer understanding of how global capital truly moves.

Those who treat currency trading as a serious financial craft—grounded in economics, structure, and psychology—stand a far better chance of long-term survival and growth. In the end, forex does not reward excitement; it rewards consistency, humility, and respect for risk.

Exchange Rate SecretsThe Hidden Forces That Drive Currency Movements

Exchange rates appear on screens every second—USD/INR, EUR/USD, GBP/JPY—yet the forces that truly move currencies are far deeper than simple supply and demand. Behind every tick lies a complex interaction of economics, policy, psychology, capital flows, and global power dynamics. Understanding these “exchange rate secrets” is essential for traders, investors, policymakers, and businesses operating in a globalized world.

At its core, an exchange rate represents the relative value of one currency against another. However, currencies are not priced like ordinary goods. They are reflections of an economy’s credibility, stability, and future prospects. The real secret is that currencies trade on expectations more than on current reality.

1. Interest Rates: The Most Powerful Silent Driver

One of the strongest and most consistent drivers of exchange rates is interest rate differentials. Capital flows toward higher yields. When a country offers higher interest rates relative to others, global investors are incentivized to move capital into that currency to earn better returns. This is the foundation of the carry trade, where investors borrow in low-yield currencies and invest in high-yield ones.

However, the secret lies in expectations. Markets often move before a central bank changes rates. If traders believe interest rates will rise in the future, the currency may strengthen months in advance. Conversely, a rate hike that is already priced in may cause little movement—or even a reversal.

2. Central Banks: Masters of Perception

Central banks do more than set interest rates; they shape narratives. Forward guidance, speeches, press conferences, and even subtle changes in language can move currencies dramatically. A single word like “persistent” or “temporary” in inflation commentary can trigger large currency swings.

The hidden truth is that central banks manage confidence as much as policy. A credible central bank stabilizes its currency even during economic stress, while a loss of credibility can trigger sharp depreciation regardless of actual data.

3. Inflation: The Currency Erosion Factor

Inflation quietly eats away at a currency’s purchasing power. Countries with persistently high inflation tend to see long-term currency depreciation. This is why emerging market currencies often weaken over decades against developed market currencies.

But the secret is relative inflation. A currency doesn’t weaken just because inflation is high—it weakens when inflation is higher than its trading partners. If inflation rises everywhere, exchange rates may barely move. Forex is always a game of comparison.

4. Trade Balance and Current Account: Structural Pressure

Countries that export more than they import generate continuous foreign currency inflows, supporting their exchange rate. Export-driven economies often enjoy structurally strong currencies over time. Conversely, large and persistent current account deficits can put downward pressure on a currency.

Yet this relationship is not always immediate. The secret is financing. As long as a country can attract stable capital inflows—foreign investment, remittances, or portfolio flows—it can sustain a deficit without currency collapse. Problems arise when confidence breaks and funding dries up.

5. Capital Flows: The Real Market Movers

Trade flows are slow and predictable; capital flows are fast and emotional. Large institutional investors, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and multinational corporations can move billions in minutes. These flows often overwhelm trade-based fundamentals in the short to medium term.

The hidden reality is that currencies are increasingly driven by financial markets, not goods markets. Risk-on and risk-off sentiment—whether investors are seeking risk or safety—can dominate exchange rate movements irrespective of domestic economic conditions.

6. Safe-Haven Myth and Reality

Certain currencies, such as the US dollar, Swiss franc, and Japanese yen, are considered safe havens. During global crises, capital rushes into these currencies, pushing them higher even if the underlying economy is weak.

The secret here is trust and liquidity. Safe-haven currencies belong to countries with deep financial markets, strong institutions, and the ability to absorb massive capital inflows without destabilization. Safety is less about growth and more about reliability.

7. Geopolitics and Power Currency Dynamics

Exchange rates are also geopolitical instruments. Sanctions, trade wars, military conflicts, and diplomatic tensions can all affect currency values. The dominance of the US dollar is not just economic—it is political and strategic.

A key secret is that reserve currency status creates self-reinforcing strength. Because so much global trade and debt is denominated in dollars, global demand for dollars remains high even when US fundamentals weaken. This “exorbitant privilege” distorts traditional exchange rate logic.

8. Speculation and Market Positioning

Currencies are heavily traded assets, and speculative positioning can exaggerate moves. When too many traders are positioned on one side of a trade, even small news can trigger violent reversals as positions unwind.

The secret lies in understanding positioning, not just data. Many major currency moves occur not because of new information, but because the market was already overcrowded. In forex, who is already in the trade often matters more than the news itself.

9. Psychological Levels and Market Behavior

Round numbers—such as USD/INR 80 or EUR/USD 1.10—carry psychological significance. These levels attract large orders from institutions, corporates, and central banks. Breaks above or below such levels can trigger momentum-based moves.

This reveals a key secret: exchange rates are partly behavioral. Algorithms, technical traders, and human psychology interact to create self-fulfilling price movements that may temporarily disconnect from fundamentals.

10. Long-Term vs Short-Term Truth

In the short term, exchange rates are noisy, emotional, and often irrational. In the long term, they reflect productivity, economic growth, institutional strength, and policy discipline. Traders operate in the short-term chaos; investors and policymakers must respect long-term fundamentals.

The deepest secret is that both perspectives are correct—but on different time horizons. Confusion arises when short-term movements are mistaken for long-term trends, or vice versa.

Conclusion: Seeing Beyond the Numbers

Exchange rate secrets are not hidden formulas or insider tricks. They are insights into how economics, expectations, and human behavior intertwine. Currencies move not just on data, but on belief, credibility, fear, and confidence. Those who understand exchange rates deeply learn to read between the lines—listening not only to what central banks say, but how markets react.

In the global financial system, exchange rates act as real-time verdicts on nations’ economic stories. To understand them is to understand the invisible forces shaping global wealth, trade, and power.

Arbitrage Opportunities Across World ExchangesUnderstanding Global Arbitrage

At its core, arbitrage is the practice of buying an asset in one market where it is undervalued and simultaneously selling it in another market where it is overvalued, locking in a risk-free or low-risk profit. When this activity occurs across different countries or exchanges, it is referred to as global or cross-border arbitrage.

World exchanges differ due to:

Time zone variations

Currency denominations

Regulatory frameworks

Market liquidity and participant behavior

Information dissemination speed

These differences create temporary inefficiencies that arbitrageurs seek to exploit.

Key Types of Arbitrage Across World Exchanges

1. Equity Cross-Listing Arbitrage

Many large corporations are listed on multiple exchanges across the world. Examples include companies listed both in their home market and overseas through American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) or Global Depositary Receipts (GDRs).

Price discrepancies can occur due to:

Exchange rate movements

Different demand-supply dynamics

Local investor sentiment

Arbitrageurs buy shares where they are cheaper and sell where they are more expensive, adjusting for currency conversion and transaction costs.

2. Currency (Forex) Arbitrage

The foreign exchange market is the largest global market and operates 24 hours a day. Arbitrage opportunities arise when exchange rates between three or more currencies are misaligned, commonly known as triangular arbitrage.

For example:

USD → EUR

EUR → JPY

JPY → USD

Even small pricing mismatches can be profitable when executed at large volumes and high speed. However, such opportunities are extremely short-lived due to intense competition and automation.

3. Interest Rate Arbitrage

Interest rates vary across countries due to differing monetary policies, inflation expectations, and economic conditions. Arbitrageurs exploit these differences through covered and uncovered interest rate arbitrage.

Covered interest arbitrage uses forward contracts to hedge currency risk.

Uncovered interest arbitrage takes exposure to currency movements in pursuit of higher yields.

Global bond markets, especially government securities, play a major role in these strategies.

4. Commodity Arbitrage

Commodities such as gold, crude oil, silver, and agricultural products trade on multiple global exchanges. Price differences may arise due to:

Transportation and storage costs

Regional supply-demand imbalances

Taxation and import-export regulations

For instance, gold prices may differ between London, New York, Dubai, and Shanghai markets. Arbitrageurs factor in logistics and financing costs before executing trades.

5. Derivatives and Futures Arbitrage

Futures and options linked to the same underlying asset often trade on multiple international exchanges. Arbitrage opportunities arise when futures prices deviate from their fair value based on spot prices, interest rates, dividends, and time to expiry.

Common strategies include:

Cash-and-carry arbitrage

Reverse cash-and-carry arbitrage

Index futures arbitrage across regions

These trades are popular among institutional players due to their scalability.

6. ETF and Index Arbitrage

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) track indices that may include global securities. When ETF prices diverge from their Net Asset Value (NAV), arbitrageurs step in to profit from the difference.

Global index arbitrage also occurs when the same index futures trade in different time zones, such as Asian, European, and US market hours, leading to temporary mispricing.

7. Cryptocurrency Arbitrage

Digital assets trade on hundreds of exchanges worldwide, often with significant price differences due to:

Capital controls

Liquidity fragmentation

Exchange-specific demand

Regulatory restrictions

Crypto arbitrage can be:

Spatial (between exchanges)

Triangular (within one exchange)

Cross-border (fiat on-ramps and off-ramps)

While highly attractive, these opportunities carry operational, regulatory, and counterparty risks.

Drivers of Arbitrage Opportunities

Several factors contribute to the persistence of arbitrage opportunities across world exchanges:

Market Fragmentation – Different exchanges operate under unique rules and participant structures.

Information Asymmetry – News travels unevenly across regions and time zones.

Currency Volatility – Exchange rate movements distort price parity.

Regulatory Barriers – Capital controls, taxes, and settlement restrictions prevent instant alignment.

Liquidity Differences – Thinly traded markets adjust prices more slowly.

Role of Technology in Global Arbitrage

Modern arbitrage is dominated by technology-driven participants. High-frequency trading (HFT) firms and institutional desks use:

Ultra-low-latency networks

Algorithmic trading systems

Co-location near exchanges

Real-time global data feeds

As a result, simple arbitrage opportunities vanish within milliseconds, leaving retail traders with limited access to pure risk-free arbitrage.

Risks and Constraints

Despite its theoretical risk-free nature, global arbitrage involves several practical risks:

Execution risk due to latency

Currency conversion and hedging costs

Regulatory and compliance issues

Settlement and counterparty risk

Sudden liquidity evaporation

In stressed market conditions, arbitrage can fail, leading to losses instead of profits.

Impact on Global Financial Markets

Arbitrage plays a vital role in:

Enhancing price discovery

Improving market efficiency

Reducing regional price disparities

Integrating global financial systems

Without arbitrage, markets would remain fragmented, inefficient, and prone to persistent mispricing.

Conclusion

Arbitrage opportunities across world exchanges are a natural outcome of global market diversity. While advancements in technology and regulation have reduced the frequency and size of these opportunities, they have not eliminated them. Instead, arbitrage has become more complex, capital-intensive, and speed-dependent.

For institutional players, global arbitrage remains a cornerstone strategy. For individual investors, understanding arbitrage provides valuable insight into how global markets function and why prices converge over time. Ultimately, arbitrage is not just a profit-seeking activity—it is a stabilizing force that keeps the world’s financial markets connected, efficient, and aligned.

Participants’ Market Coverage1. Types of Market Participants and Their Coverage

Financial markets are populated by a wide range of participants, broadly categorized into institutional investors, retail investors, intermediaries, proprietary traders, hedgers, and regulators. Each group covers markets differently.

Institutional investors—such as mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and endowments—typically provide broad market coverage. They operate across equities, fixed income, commodities, real estate, and increasingly alternative assets like private equity and infrastructure. Their long-term mandates require diversified exposure across sectors and geographies, making them key providers of stable capital. Because of their size, institutional investors influence benchmark indices and play a central role in capital allocation.

Retail investors generally have narrower market coverage. Their participation is often concentrated in domestic equities, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), derivatives for speculation or hedging, and popular thematic investments. While individually small, their collective impact can be significant, especially during periods of heightened sentiment or technological access through online platforms.

Proprietary traders and hedge funds focus on selective but deep market coverage. Rather than covering all markets broadly, they specialize in specific strategies—such as arbitrage, macro trading, statistical strategies, or event-driven trades—across multiple instruments. Their coverage is opportunistic and dynamic, shifting rapidly as risk–reward conditions change.

2. Market Coverage Across Asset Classes

Participants’ market coverage varies significantly by asset class.

In equity markets, coverage is typically broad due to high liquidity, transparency, and accessibility. Large-cap stocks attract coverage from almost all participant types, while mid- and small-cap stocks may have thinner coverage, often dominated by domestic institutions and select funds. This uneven coverage can create pricing inefficiencies in less-followed stocks.

In fixed income markets, coverage is more fragmented. Government bonds enjoy deep participation from central banks, institutions, and foreign investors, while corporate bonds—especially lower-rated or illiquid issues—have limited coverage. This asymmetry affects liquidity and price stability.

Derivatives markets—including futures and options—are heavily covered by hedgers, speculators, and arbitrageurs. Coverage here is driven by leverage, risk management needs, and the ability to express views efficiently. Participants often focus on the most liquid contracts, leaving less popular maturities or underlyings with sparse participation.

In commodity and currency markets, coverage is global but concentrated among professional participants such as exporters, importers, banks, and macro funds. Retail participation exists but is relatively smaller compared to equities.

3. Geographic Market Coverage

Participants’ market coverage also differs by geography. Developed markets generally enjoy extensive coverage due to strong regulation, transparency, and liquidity. Emerging and frontier markets, while offering higher growth potential, often suffer from limited coverage because of political risk, currency volatility, and regulatory uncertainty.

Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) play a crucial role in extending market coverage to emerging economies. Their participation improves liquidity, governance standards, and global integration. However, reliance on foreign capital can also introduce volatility, as global risk-off events may trigger sudden withdrawals.

Domestic institutions help stabilize coverage by providing a local capital base that understands country-specific risks. Balanced participation between domestic and foreign players leads to healthier market development.

4. Time Horizon and Coverage

Market participants differ in their time horizons, which influences how they cover markets.

Long-term investors—such as pension funds and insurance companies—cover markets with a focus on fundamentals, valuation, and sustainability. Their steady participation dampens excessive volatility and supports long-term price discovery.

Short-term traders, including high-frequency traders (HFTs) and day traders, cover markets at a micro level. Their activity is concentrated in highly liquid instruments and contributes to tight bid–ask spreads and rapid price adjustments. However, their coverage is shallow in illiquid or less-followed markets.

The coexistence of multiple time horizons enhances overall market efficiency. When one group withdraws, another often fills the gap, maintaining functional coverage.

5. Role of Intermediaries in Market Coverage

Intermediaries such as stock exchanges, brokers, market makers, and clearing institutions are critical to participants’ market coverage. Market makers, in particular, ensure continuous two-way quotes, enabling participants to transact even during periods of stress. Without them, coverage would become fragmented and liquidity would evaporate quickly.

Technological advancements have expanded coverage by reducing transaction costs and improving access. Electronic trading platforms allow participants to cover multiple markets simultaneously, breaking down geographic and structural barriers.

6. Information, Research, and Coverage Quality

Market coverage is not only about participation volume but also about information depth. Analysts, rating agencies, data providers, and financial media enhance coverage by producing research and disseminating information. Well-covered markets tend to be more efficient, as prices reflect available information more quickly.

Conversely, markets or securities with poor research coverage may experience mispricing. While this increases risk, it also creates opportunities for skilled participants who can conduct independent analysis.

7. Regulatory Influence on Market Coverage

Regulation shapes participants’ market coverage by defining who can participate, how much risk they can take, and which instruments are permissible. Strong regulatory frameworks encourage broader participation by building trust and reducing systemic risk. Overregulation, however, may discourage participation and reduce coverage, particularly in innovative or niche markets.

Balanced regulation promotes inclusive coverage while safeguarding market integrity.

8. Implications of Participants’ Market Coverage

Participants’ market coverage has far-reaching implications. Broad and diversified coverage enhances liquidity, stabilizes prices, and improves capital formation. Narrow or uneven coverage can lead to volatility, liquidity gaps, and systemic vulnerabilities.

For investors, understanding coverage patterns helps in identifying risks and opportunities. Markets with limited coverage may offer higher returns but require careful risk management. For policymakers, fostering balanced participation supports economic growth and financial stability.

Conclusion

Participants’ market coverage is the backbone of financial market functioning. It reflects how different actors engage across assets, regions, and time horizons, shaping liquidity, efficiency, and resilience. A well-covered market benefits from diverse participation, robust information flow, and effective intermediation. As markets evolve through globalization and technology, understanding and adapting to changing coverage dynamics remains essential for all stakeholders in the financial ecosystem.

Comprehensive Financial Market CoverageScope, Importance, and Modern Dynamics

Financial market coverage refers to the systematic analysis, tracking, interpretation, and communication of developments across global and domestic financial markets. It includes equities, bonds, commodities, currencies, derivatives, alternative assets, and emerging financial instruments. In today’s interconnected and fast-moving economic environment, effective financial market coverage plays a critical role in informing investors, policymakers, institutions, and the general public. It bridges the gap between complex market activity and practical decision-making by transforming raw data into actionable insights.

Understanding Financial Market Coverage

At its core, financial market coverage involves monitoring market movements, economic indicators, corporate actions, policy changes, and geopolitical events that influence asset prices. It spans real-time news reporting, in-depth research, technical and fundamental analysis, macroeconomic commentary, and long-term thematic insights. Coverage may be delivered through financial news platforms, brokerage research reports, institutional notes, data terminals, social media channels, and independent analysts.

Financial market coverage is not limited to price reporting. It also explains why markets move, how different assets are interconnected, and what potential future scenarios may unfold. This interpretive layer is what differentiates meaningful coverage from mere information dissemination.

Key Segments of Financial Market Coverage

Equity Markets

Equity market coverage focuses on stock indices, individual companies, sectors, earnings results, valuations, corporate governance, and mergers and acquisitions. Analysts assess both fundamentals (revenues, profits, balance sheets) and technical factors (trends, volume, momentum). Equity coverage is essential for retail investors, portfolio managers, and traders seeking alpha or long-term growth.

Fixed Income and Debt Markets

Bond market coverage tracks government securities, corporate bonds, yield curves, credit spreads, and interest rate expectations. Since debt markets are closely tied to monetary policy, inflation, and fiscal conditions, their coverage is crucial for understanding economic health. Bond market signals often precede equity market trends, making this segment highly influential.

Currency and Forex Markets

Currency market coverage analyzes exchange rate movements driven by interest rate differentials, trade balances, capital flows, and geopolitical risks. Forex markets operate 24/5 and reflect real-time global sentiment. Coverage helps businesses manage currency risk and traders identify macro-driven opportunities.

Commodities and Real Assets

This segment includes energy (oil, gas), metals (gold, copper), agricultural products, and increasingly, carbon and environmental credits. Commodity coverage links supply-demand dynamics, weather patterns, geopolitical tensions, and industrial demand. It is vital for inflation analysis and global growth assessment.

Derivatives and Structured Products

Coverage of futures, options, swaps, and structured instruments focuses on hedging activity, leverage, volatility, and market expectations. Derivatives often reveal institutional positioning and risk appetite, making them an advanced but powerful area of market intelligence.

Role of Macroeconomic and Policy Coverage

A significant pillar of financial market coverage is macroeconomic analysis. This includes tracking GDP growth, inflation, employment data, central bank decisions, fiscal policies, and global economic cycles. Central banks such as the Federal Reserve, ECB, and RBI heavily influence markets through interest rates, liquidity measures, and forward guidance. Accurate coverage of policy signals helps investors anticipate shifts in capital flows and asset valuations.

Geopolitical developments—trade disputes, wars, sanctions, elections—also form a critical part of market coverage. In modern markets, political risk can move prices as strongly as economic fundamentals, making integrated analysis indispensable.

Technology and Data in Modern Coverage

Technology has transformed financial market coverage. High-frequency data, algorithmic analysis, artificial intelligence, and alternative data (satellite data, social media sentiment, supply-chain metrics) are now integral. Market coverage today combines traditional financial statements with real-time analytics and predictive modeling.

Digital platforms enable instant dissemination of insights, while dashboards and visualizations help users interpret complex information quickly. However, this abundance of data also increases noise, making credibility, context, and analytical rigor more important than ever.

Importance for Different Stakeholders

Investors and Traders: Financial market coverage guides asset allocation, risk management, and timing decisions.

Institutions and Corporates: It aids capital raising, hedging strategies, and strategic planning.

Policymakers and Regulators: Market coverage helps assess financial stability and systemic risks.

General Public: It improves financial literacy and awareness of economic trends impacting daily life.

Challenges in Financial Market Coverage

Despite its importance, financial market coverage faces several challenges. Information overload can overwhelm users, while short-termism and sensationalism may distort long-term perspectives. Bias, conflicts of interest, and misinformation—especially in the age of social media—pose risks to credibility. High-quality coverage must balance speed with accuracy, depth with clarity, and opinion with evidence.

The Future of Financial Market Coverage

Looking ahead, financial market coverage is likely to become more personalized, data-driven, and interactive. AI-generated insights, real-time scenario analysis, and cross-asset integration will enhance decision-making. At the same time, human judgment, ethical standards, and contextual understanding will remain irreplaceable.

Conclusion

Comprehensive financial market coverage is the backbone of informed participation in the global financial system. It connects data with insight, markets with the economy, and short-term movements with long-term trends. As markets grow more complex and interconnected, the value of accurate, unbiased, and insightful financial market coverage will only increase—making it an essential tool for navigating uncertainty and opportunity in the modern financial world.

Impact of Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) on InvestmentsRole of FIIs in Capital Formation